This summer, with a collective of Black Canadian artists, critics and curators, I attended the opening of the 10th Berlin Biennale, curated by four people of African descent. Being in Berlin, the art city, in art spaces whose audiences were responsive to new stewardship, was a unique experience. In other words, it was really nice to be around so many Black people, from across Europe and all over the world, who work in the arts. It is rare to come together in this way to look, and to celebrate. The challenges of inclusion, of negotiating institutional support, and of working toward equitable practices of representation, seemed to be shared by many of these art workers; from our respective contexts we had similar stories. Being there gave me renewed energy to both witness, and support, the immense sea change that has been happening for Black artists in Canada in the recent past. I’ve been writing about art for half a decade, and I’ve seen a dramatic change in the past year. Black artists are invited to show more, they are written about more frequently, and their efforts are demonstrably recognized. Looking back at the interviews, essays, videos and features Canadian Art has commissioned and published this year, one finds Black writers and artists and curators addressing the activities and concerns of Black arts in Canada, and in the diaspora at large. Though Black art in Canada is not new, the critical discourses around it are still in formation. We are negotiating how to speak about these practices, and how to give ethical, and nuanced, attention to its practitioners.

In the fall, interdisciplinary artist Kapwani Kiwanga was awarded the $100,000 Sobey Art Award. Kiwanga, whose art career started after early studies in anthropology and comparative religion, was interviewed by Canadian Art twice this year. Of “Clearing,” the art exhibition she presented at the Glenhyrst Art Gallery of Brant last February, near where she was born and raised on disputed Haudenosaunee territory, she said, “I felt I like I had to address that feeling that stayed with me and has affected how I feel when I go elsewhere. I grew up in a colonial country and that is very particular.” After her Sobey win, she talked about some of the frames and language often put to her work by critics: “They’ll say it’s about identity and postcoloniality, but ‘postcolonial’ is a word I would never use. I never use that term. Labelling it that way can negate a lot of things. That ‘postcolonial’ label essentializes parts of my origins. It’s a taxonomy. And we know what that does.”

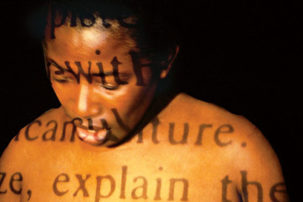

Poet and art worker Cecily Nicholson, who was recognized this year by the Governor General for her collection of poetry “Wayside Sang,” contributed to our summer Translation issue. “what is daily what was past all subterfuge, as inhumane is made / possible, ill making ill solitary gains surrealistic some systems make / distinctions imaginary—subverted in the presence of segregation,” she wrote in “poem is a score.” Looking for humanity in correctional institutions, Nicholson’s observations are not dissimilar to a feeling of being racialized in the arts. Taxonomic impulses and brisk recourse to identity politics when discussing work by racialized artists can dangerously limit forms of care, solidarity and self expression that do not fit into existing conceptions of Canadian art. Our winter cover by the emerging Toronto painter Oreka James features an image of black hands reaching out from holes in two perpendicular walls with their fingers gently, blindly, interlaced and bodies out of view. The gesture is one of solace, and concord. James’s figures, drawn in rough oil stick settings, are often faceless—their bodies have negotiated how to maintain privacy in relation to the audience’s gaze, a privacy that becomes a manner of self-ownership. “I’m making my work strictly for Black people to enjoy or to understand. If they’re looking for happiness, they’ll find it,” she told the writer Tiana Reid in the feature “I Do See Myself.” “At stake is how the anxious beauty of Black art undermines the sanctity of the self-assured individual,” Reid writes, “or, to put it plainly, how Black people invent moments of respite.”

As an understanding of the diverse and entrenched histories of Black Canada becomes a part of our everyday, we will increasingly allow for new ways of being.

In their article “We Are Each Other’s Medicine,” Taylor Renee Aldridge and Jessica Lynne present a strategy of care for existing in the art world. “Through our work we find ourselves in the centre of art worlds that do not always know how to care for blackness,” writes Aldridge. “[As] critics and curators and art workers, we navigate Du Bois’s double consciousness and that negotiation—personal and political—is also physical.” In their epistolary text they describe the enclave within which they work, and the ways in which pleasure, in itself, can become an act of resistance. They show an example of one of the many ways in which Black artists and art workers are making space for themselves, and for each other, within a mostly white art world. These are new and exciting spaces that I am only learning to recognize as I adjust to the realization that our community exists, and thrives, within such unseen networks. Also, I see that mentorship might not always come in the shape we imagine. And that the reasons to continue can sometimes feel evanescent. “I’ve found pleasure,” writes Lynne, “in understanding that I am not alone.”

These spaces and networks take many forms. In “Look What’s Possible,” Nataleah Hunter-Young writes about a Black lesbian strip party in Los Angeles in the early 2000s, documented in Leilah Weinraub’s mixtape-style documentary Shakedown. “Weinraub offers us an example of a past world where the fissure of prioritizing Black queer and trans joy, within fervent anti-Blackness, inspires imaginings of comparable futures,” explains Hunter-Young, “and it is through these reflections that we get closer to a tomorrow that is more liveable than today.”

Attempts as such world-making are visible in the practices of different Black Canadian artists. Speaking of her eponymous live, musical performance “Elle Barbara’s Black Space,” presented at the MAI (Montréal, arts interculturels) earlier this year, Barbara describes how she finds herself “in a social environment where there’s all these recurring buzzwords that are rooted in identity politics, which is quite contemporary. It wouldn’t have been possible for me to not to implement some of those notions into the work that I did.” However, for Barbara, the underlying sentiment of the musical production is an “expression [that] positions itself as being in looking out, looking out to a different possible future in order to imagine a better outcome for Black people.”

Another approach exists in the practice of the sculptor Tau Lewis, who maintains a special, intimate relationship to her artworks; one that is unbroken by the strictures of the art market. “I would normally spend up to two months producing one of them, so it’s been really emotional and really intense. Not just the process of creating them but also being with them at the fair [after]… all the time that I’ve spent getting to know and getting to love these things for what they are,” the artist said after winning the Frame Prize at Frieze New York last spring. Lewis stays in touch with her works, giving herself permission to visit them if ever she needs to, in whichever collection they may be. “I’m lucky to be able to be transparent with my collectors about how I want these things to exist, and how I want these things to live.” Lewis, in her way, redefines the relationship between artists and artwork. A similar intimacy exists in the works of Scarborough artist Erika de Freitas. The mourning gestures in her abstract sculptures are traces of her complex emotions about losing her mother.

Each of these concerns about intimacy, world making, security and survival seem necessary to considerations of Black life and, in turn, to how we think about work by Black artists. Thus, the attention to Black Canadian art also signals the importance of having a vocabulary for Black canadian aesthetics, one that can help us move beyond what Rinaldo Walcott, in a FUSE article from 1999, called “exuberant celebration or racist denunciation.”

We still don’t have a comprehensive vocabulary to address—and critique—the range of Black art practices in Canada, but we are getting there.

Several articles this year have attempted to untangle the nexus of Black Canadian diasporic cultures. In her article “We Aren’t a ‘We’” Reid wrote about a queer Caribbean diaspora by looking at an exhibition organized by the collective Ragga NYC at Mercer Union. The collective, she found, prioritizes “chosen family over the performance of networking, and grassroots political organizing over fitting into a stale scene.” Ultimately, their work, and how they operate together, provide no easy answers to what blackness or queerness might mean in a Canadian art context. How Black artists and art workers create and appreciate is one possible commonality. In any case, “RAGGA runs with our open secrets and thus insists that we do not always have to unpack the terms of the day in order to live them.” In Katherine McKittrick’s contribution to the Pleasure issue, “Hues and Grooves,” she draws attention to rhythm and pure pleasure of aesthetic appreciation. “[O]ften the Black creative text is more interesting and more innovative than the theory,” she finds. “It’s a lot more fun, and also—particularly with music or visual art—it helps you experience what you cannot say, or what cannot be textually expressed.” McKittrick stresses the importance of Black creative cultures: “How we relate to each other matters and how we tell each other stories matters because the stories are often embedded with codes and clues about how to live in this world ethically.”

In her article “Ethics Beyond Language,” the writer Nasrin Himada exposes the ethical disaster of appropriation in her study of how NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! was used by a Prix de Rome-winning artist without permission, or reprisal. “[O]ur actions,” she finds, “are conditioned by the ways in which we position ourselves in relation to others.” Himada’s writing is a great example of how to hold people accountable for intangible wrongs. We still don’t have a comprehensive vocabulary to address—and critique—the range of Black art practices in Canada, but we are getting there. Next, it will be important to look back at Black artistic production over the past half-century, and beyond. This will give us context for understanding current practices, and shed light on senior artists who have been working for a long time without institutional support or recognition. Hopefully, in the years to come—following the example set by BAND with their Michael Chambers retrospective—these artists will be honoured in retrospectives in major institutions. As an understanding of the diverse and entrenched histories of Black Canada becomes a part of our everyday, we will increasingly allow for new ways of being.

P.S.

Other highlights from this year include: our studio visit with Syrus Marcus Ware, in which he discusses his Activist Portrait Series; curator Denise Ryner’s “Fair-Weather Funding,” in which she asks if temporary diversity funding programs can “ever fully address the ongoing structural exclusion of BIPOC arts professionals from the leadership and creative positions that define contemporary culture”; Luis Jacob’s review of “It’s About Time: Dancing Black in Canada 1900 to 1970,” an exhibition curated by Seika Boye at Dance Collection Danse; Liz Johnson Artur’s efforts to rewrite Black representation; Madelyne Beckles’s playful take on second-wave feminist theory; a review of Adrian Piper’s recent MoMA retrospective “A Synthesis of Intuitions”; Kandis Williams’s discussion of image-making and abstraction; Nick Cave’s creative strategies; Mickalene Thomas’s call for Black audiences in major institutions; Denise Ferreira da Silva’s reframing of questions around climate change; and Kelsey Adams’s review of the Royal Ontario Museum’s “Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art.”

Kapwani Kiwanga, Vumbi, 2012. Video, 30 minutes. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin, Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris, and Goodman Gallery, South Africa.

Kapwani Kiwanga, Vumbi, 2012. Video, 30 minutes. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin, Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris, and Goodman Gallery, South Africa.