Sometimes the words and ideas of black women, when cited, become something else. Sometimes the ideas of black women wear out and wear down even though these narratives provide the clues and instructions to imagine the world anew. Often the words and ideas and brilliance of black women remain unread. The words and ideas of black women go uncited.

– Katherine McKittrick, “Worn Down”

In an email sent July 31, 2017, Rotterdam-based, Lebanese artist Rana Hamadeh asked poet M. NourbeSe Philip for “blessings and permission to mention Zong! and point towards it” in her upcoming exhibition at the Witte de With Centre for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam. About a month later, Philip responds, apologizing for her delay in answering, and politely expresses her inability to engage with the query as her sister is dying of cancer, and she is “at this point…unable to respond intellectually to [Hamadeh’s] engagement with and queries about using Zong!” Though Hamadeh received no consent from Phillip, she nonetheless forged ahead with her project, appropriating Philip’s seminal poetry book to create an operatic work titled The Ten Murders of Josephine (2017), which borrowed heavily from Zong!’s material, form, and content.

Zong!, which took Philip seven years to research and write, is based on the Gregson v. Gilbert report, a document which details the trial of an insurance claim following what has become known as the Zong massacre: the murder of 150 Africans on board a slave ship that got lost at sea in November of 1781. The captain, who had ordered the massacre so as to collect the insurance money on each human loss, was not held responsible for the murders. Philip’s Zong! was instrumental in helping this case become well-known, and acts as a public archive of the murders that took place. In the essay at the end of Zong! Philip writes that by using only the words of the legal decision Gregson v. Gilbert—the only document that exists relating to this massacre—she is able to create a poem that ushers us into the telling of a story “that cannot be told yet but must be told.”

The first time I saw Philip perform Zong! I was living in Los Angeles and auditing a UC Riverside class taught by the poet and scholar Fred Moten, who had invited Philip to read. Zong! is a long-form poem that experiments with the poetics of fragmentation. It’s an historic and legendary poetry book and unprecedented in scope. It’s also more than just a book; it’s an archive, a memory-place, where one goes to pay respect to those who died, to remember them and to mourn them, to be with them, to hear them, to speak their names, to listen, to sing, chant and dance. To engage with the reading of the poem is to engage with the spirit of life as much as death.

Philip is based in Toronto and has lived there for years. Her writings depict the cultural, social and political fabric of the city as it is experienced by its Black residents. She has written extensively on anti-Black racism in Canada, specifically in regards to the city of Toronto. Each year, Philip organizes a collective reading of Zong! on the anniversary of the massacre. In these readings/performances Philip facilitates an improvisation—of dance, music, and singing as the words of the poem are read out loud—that spearheads a ritual, one that can only emerge out of collective witnessing and participation. These rituals are not about understanding what happened on that fateful night, but more about honouring and mourning those whose life story got lost at sea, who were disappeared. These rituals are about creating space for these stories to appear in the world again, to come to life through a spiritual and somatic experience.

It’s not just an issue around Blackness, or an issue of a Black woman having her work stolen. More central and more important is, how do we treat the other who is not ourselves? Can I see your pain?

Rana Hamadeh’s exhibition The Ten Murders of Josephine is structured through the explorations of the testimonial subject and that of the meaning voice is given. Hamadeh draws on several “cues” to create the compositions for the opera, one of which is the case of the atrocities of the Zong massacre. In her initial letter to Philip, where she asks for her “blessings and permission,” which she sent only six weeks before the opening of the exhibition, Hamadeh specifies that she wants to use “the logics of [Zong!]” as well as Zong!’s typographic logic to build on the rhythm of her sonographic compositions. Hamadeh also wants to use Zong!’s layout and “the way the layout builds its intensity” as reference. After the opening of Hamadeh’s show, Philip realizes that her work had nevertheless been used despite her declining the invitation to participate in any conversation with Hamadeh about this precise engagement in the exhibition.

In the exhibition pamphlet meant for museum visitors, Hamadeh, in a flippant way, references Philip, but does not give appropriate credit or acknowledge the work of Philip in bringing the Gregson vs Gilbert case into the public sphere through the formation of Zong!. As scholar and critic Kate Siklosi has written, “out of the many interviews Hamadeh has done, none link her work with Philip or speak of the exhaustive archival research Philip has done to bring the legal case of the Zong massacre back into our contemporary imaginary.” The irony in all this is that Hamadeh’s exhibition points to what she calls the “erased archive of erasure,” and as Siklosi further points out, “Hamadeh’s work doesn’t just take an archive of erasure as its subject matter—by erasing Philip’s work, her work contributes to an ongoing archive of erasing Black presence and subjecthood that Philip’s work, including Zong!, was and is resisting.”

In August of 2018, Philip published a website called “Set Speaks,” which documents her correspondence with Hamadeh, as well as with Philip’s publisher and the Witte de With gallery, who produced the exhibition. In the “About” section, Philip lays out in detail the events that have occurred to date and names this essay, The One Murder of Rana Hamadeh or Somebody Almost Ran Off Wid Alla My Stuff. In her own words, Philip makes clear that her intention in creating this platform is to bring these issues to the public, especially the scholars and writers familiar with Zong!.

On August 19, 2018, I interviewed Philip about Set Speaks and how she was feeling in having just released all the documentation regarding this abhorrent act. The blog is meant to open up conversations around these issues of appropriation and citation. And reminds us that this act of extraction is not disconnected from “the way Black people have been positioned, coming out of the history of slavery, that African descended people own nothing, and do not have proprietary rights because at one time they didn’t have it for their own bodies.” What is incredibly poignant here, and what I gleaned from our conversation, is how our actions are conditioned by the ways in which we position ourselves in relation to others.

I asked Philip: Zong! is so much about opening the possibility for new intimacies to emerge, and if appropriation is used in the way it has been by Hamadeh, then how is it another form of murder, as her essay title suggests? The act of Hamadeh’s appropriation is precisely traumatic on this level because Zong! is not just a book. Philip replies:

“For me as a thinker, and as a writer, the spiritual work in a larger sense is attempting to restore, attempting to repair, attempting to make whole again, and in some instances, it can’t ever be whole again, that which was broken. What is astonishing about performances of Zong!, however, is how it affirms something about the role of art, because although we have read, and are reading, about this historically traumatic situation of people being disposed of as things, not even murdered as humans, in order to collect insurance money, the performance leaves participants in a place that is very different from what one would expect. One would think that when you immerse yourself in Zong! and the events it engages with, you would feel weighted with the freight of that history. I believe that the reason for that is that the readers literally have ‘taken time’ within which and so as to hold those experiences – of the other, of the stranger, of the lost. Of the ‘denamed’ rather than the unnamed. Rana Hamadeh, after having ‘taken’ my work, after having used my work without permission, believing she was entitled to my blessing for her unauthorised use – essentially her theft of my work, her attempt to ‘run off wit alla my stuff’—could not take the time to respond to my response that my sister was dying and therefore I could not engage with her request. She attempted to establish a false intimacy, revealed by the inappropriate use of the word blessing, which she had neither earned nor deserved, no doubt expecting that this would obscure her unethical practices.”

Knowing and experiencing Zong! in this way, and having been in conversation with Philip about her work and this particular situation, it is clear to me that in an encounter with Zong!, if one is engaged with its intention and purpose, “one needs to take into account the other.” As Philip said, “It’s important to factor that in and ask what it means to be here? What has happened to me is very much tied up to what has happened to them. It’s not just an issue around Blackness, or an issue of a Black woman having her work stolen. More central and more important is, how do we treat the other who is not ourselves? Can I see your pain?” Philip tells me that what stuck out for her in the initial correspondence with Hamadeh is how after she wrote back declining the use of Zong! in her exhibition, explaining that her sister was dying and she needed to go and care for her, Hamadeh never responded. Philip tells me, “The absence of a fundamental human response challenged me. She didn’t have the courtesy to write back…it begins there for me, for the work that Zong! bids us do and for how we treat and interact with each other.”

Reading Zong! necessitates a commitment to honouring the existence of those who were murdered on that ship, the ones who died. The effect is nothing short of transformation. I keep Zong! safe on my bookshelf. Upright, I make sure it’s well kept. When I am reading it, I don’t just put it down anywhere. If it’s on my side table, or on my desk, or in the kitchen on the counter, I make sure nothing is around it that might damage it, or spill on it, or soil it. Once I almost put my cup of coffee on the cover, and immediately winced. The reason is I know the book contains life—it is about life, as much as it is about death. Zong! conditions a space for mourning and resurrection, to pay tribute and honour, memorialize and pray to/with the communities that get created when these readings happen, alone or together. It’s about mourning that life, at the same time giving life to the 150 people who were murdered. Giving them life in the sense that their spirits, memories, voices, names, might suddenly be called through the words of the narrator Setaey Adamu Boateng, they might appear, their presence felt in the room, on our tongues, in our mouths, in our hearts. Zong! touches one at their core, and if that doesn’t change you, what will?

M. NourbeSe Philip will be in conversation with Katherine McKittrick and El Jones on Saturday, October 20th at the Congress of Black Writers and Artists 2018: An Argument for Black Studies in Canada in Toronto.

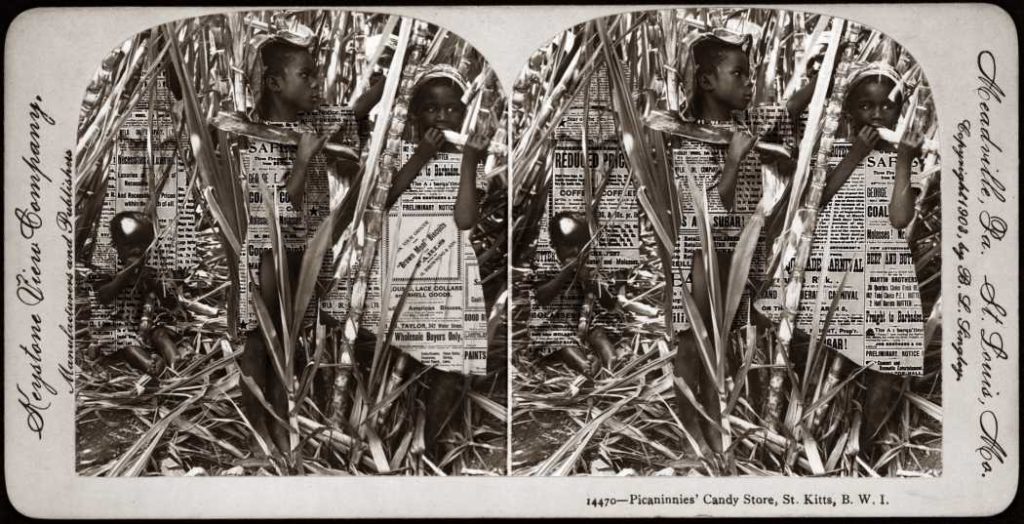

Bushra Junaid, Sweet Childhood, 2017. Archival photograph and archival text printed on backlit fabric panel. Courtesy the artist.

Bushra Junaid, Sweet Childhood, 2017. Archival photograph and archival text printed on backlit fabric panel. Courtesy the artist.