The late Vivian Maier—whose first Canadian show is currently on view at Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto—may be a 20th-century street photographer, but her case is suggestively contemporary.

Maier was a Chicago nanny, born in New York in 1926 to a French mother and Austro-Hungarian father. She was illegitimate, part of a line of illegitimate daughters. At age 6, she moved to her family town in France with her mother and stayed there until she was 12. Then she moved back to New York, then back again to France at 24, finally returning to New York two years later, and eventually moving to Chicago where she settled and began her career in childcare, and as an unsung photographer. A misfit and thus an observer on both continents, she would nanny for the rest of her life for affluent families, mostly in the Chicago suburbs (she was even hired by Phil Donahue for a year).

In the words of one of Maier’s now-grown-up charges, recently quoted in Artforum, she was “blunt and opinionated,” the kind of woman who “used lemon juice and vinegar to wash her hair, wore men’s shirts because she claimed they were made better, never shaved her legs, swore in French, and could recite entire O. Henry stories from memory.” In a BBC documentary from earlier this year, Vivian Maier: Who Took Nanny’s Pictures?, Jim Dempsey, proprietor of a Chicago movie theatre she frequented and now a gallerist, describes her as “the type of person I think you could potentially wonder if she was a little crazy.” Although she averted fame in her lifetime, a portrait of her has quickly emerged: troubled, guarded, perpetually single, strident about her liberal beliefs (when asked), hoarder, eccentric and fiercely, if quietly, intrepid. Those who knew her seem to agree on one thing: had she lived to see her career skyrocket the way it has, she would have been very uncomfortable.

The posthumous discovery of her work is the result of an auctioning off of five storage lockers, the contents of which went under the gavel in 2007 because Maier couldn’t make rent. (Maier kept almost all of her contents in storage; in the words of Dempsey, “she didn’t seem homeless, but she seemed close.”) Roger Gunderson, who purchased the contents, threw out the things that appeared to lack value (including documents that some would now die to see). He pieced off the rest at auction. Maier made few prints during her lifetime, and when she did they were often done at a drugstore, so the majority of the collection was film rolls and negatives. John Maloof, an amateur Chicago historian, got the lion’s share; artist and carpenter Jeff Goldstein, a fraction of whose collection is now on view at Bulger, got another, smaller portion. Both are now spending much of their time handling Maier’s estate.

Maier’s rise is due in no small part to the Internet. After purchasing Maier’s work, Maloof wrote a what-do-I-do-with-these post on Flickr; he also developed some of the negatives and began selling them on eBay before photographic artist Allan Sekula told him to stop because the work seemed of significant aesthetic interest. In 2009, Maloof was online when he discovered Maier was dead; he saw her name on an envelope and Google brought him to an obituary, published just days before he thought to search. A 2011 exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center was an instigator, with much transpiring online afterwards. Maier had gone viral, on sites like Gawker and Buzzfeed, and through social media. My own experience: in January 2011, I received a group email from a friend with a link to a Guardian article and an appended exhortation, “Hi guys, it’s the Henry Darger of street photography!”

Maier’s story is still unfolding, detail after detail. More revelations are likely forthcoming in Maloof’s documentary about her, which has its world premiere at TIFF next month. But what of her work? How do we know it’s good? More relevant, can we judge its worth apart from the story of how we came to see it, and indeed, should we?

First things first: Maier cannot be part of her own selection and curation at all. There are no surviving directives in her personal effects as to how her work is to be handled, so what we get are highlights as others see them. Because so many of her shots were not printed, and if they were printed, do not exist in the large, crisp, 12” by 12” format in which they’re now commonly shown, we must be content with the notion that somebody else has intervened. In the case of Bulger Gallery, and thus of Goldstein’s collection, this person is master printer Ron Gordon. He is evidently skilled at his trade, but still, one wonders.

The subjection of Maier’s legacy to the hands of others seems curiously of-the-moment. “The Henry Darger of street photography” is a fine place to start: Chicago provenance aside, Maier is an archaeological find. She can be put beside the resurgent phenomenon of the outsider artist, parodied eight years ago in films such as Junebug, but still lingering enough in 2013 to have reached an apparent pitch at this year’s Venice Biennale exhibition “The Encyclopedic Palace.” It’s hard, actually, to believe Maier wasn’t included in curator Massimiliano Gioni’s sprawling show, for she fits his deceased-artist agenda so neatly: marginalized while living and somewhat mentally unstable; obsessive and prolific; and, in turn, an artist-archivist, tracking certain types of lives and ideas with indexical persistence.

And so it is that Maier, after her death, has become a contemporary artist. As Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery director Nigel Prince put it to me in a 2011 interview, “I don’t necessarily believe ‘contemporary’ means something that was made yesterday or today; it can mean something that was made a long time ago, if the issues and propositions within that work still carry meaning to society and to visitors.” Maier’s shaping by curators runs in tandem with her shaping by the Internet. As a street photographer with a voracious, spying eye, and as someone prone to take photos of herself (regardless of whether they were intended for public consumption) her body of work resembles an Instagram account. Selfies and creeper shots abound.

The consumption of her work also smacks of Internet ahistoricity. Maier is often lavished with superlatives like “genius” but rarely put into the context of the street photographers she seems to have consciously emulated: Europeans such as Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Kertész, Model and Brassaï, and Americans such as Frank, Winogrand and Arbus. Could we tell a Maier apart from the work of any of these? Would it hold up in juxtaposition?

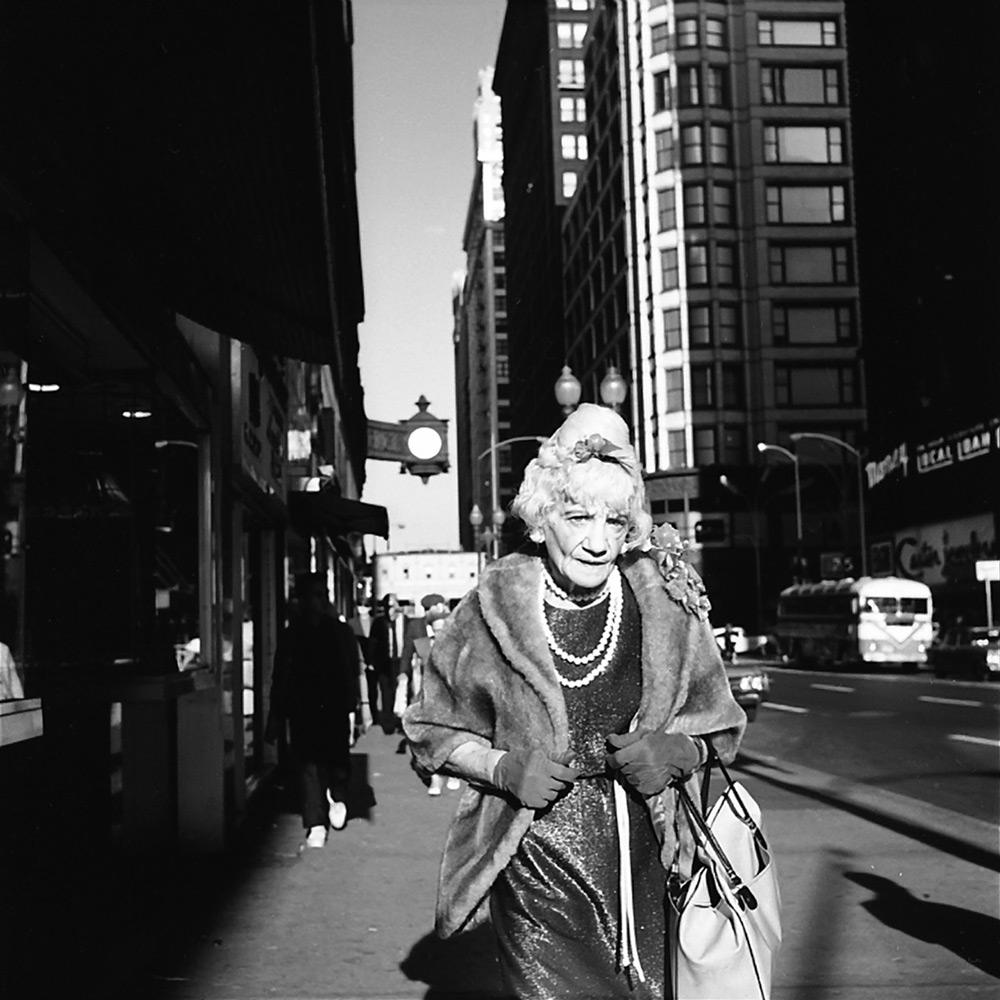

Does it matter? Maier’s work seems inescapably enriched by the uncovered anecdotes about her life and process; we must know the things she probably didn’t want us to know, or the work just doesn’t resonate as well. She used a Rolleiflex, holding it unassumingly at her abdomen as she patrolled the Chicago streets in her scarves, coats and sundry layers. Many of her subjects were unaware she was shooting them, and probably unaware, even, of her. This is in the tradition of Brassaï—who, however, was legendarily more comfortable, reputedly timing café exposures to the length of a cigarette. Yet Maier herself still registers so often in her work. We now know what she looks like from those aforementioned selfies; there are also photos in which her recognizable shadow looms, sometimes coming very close to her oblivious subjects. Then there are her photographs of children—her own charges, who were aware of being photographed. A haunting image in the Bulger exhibition, one of Maier’s best, shows Inger Raymond, whose childhood was essentially recorded by Maier, looking through the grille of substrate steel cords in a cracked concrete sewer pipe that Maier asked her to crawl into. That’s some high-concept babysitting.

If an understanding of Maier’s uniqueness blooms within the context of her workaday life, her adeptness as a photographer also comes out as a result of our prying. We only see Maier’s work as an archive, impossible to parse according to her wishes, and sublime in its volume. According to her contact sheets, some of which are available online, she was a remarkable technician: her “hit rate,” the amount of plum shots per roll of film, was high, and she rarely took multiple photos in the same place. Her Cartier-Bressonian “decisive moments” seem to happen all in one try, with eerie precision. More poignantly, many happened undeveloped, seen only once by Maier through her viewfinder. In this way, the very materiality of photography, its developed evidence of labour and perception, seems beside the point for her.

Maier’s contemporaneity, finally, rests not on her life, but its lesson. It’s a bittersweet one: that of an artist toiling and dying unrecognized and homeless, and just on the cusp of discovery. But it’s mostly sweet. Certainly it’s with the zeitgeist. On a more monastic level, Maier testifies to the purity of practice, to satisfaction of work for work’s sake, without the need for audience validation. At the same time, Maier’s example suggests the different and rapid ways in which delayed fame can unfold with the influence of the Internet. Maier’s story is consonant, for example, with the Oscar-winning documentary Searching for Sugar Man and its Cinderella story of Rodriguez, a Detroit folk musician who, after a failed recording career in America, found fame in South Africa—unknown to him until a music journalist decided to seek him out. Like Rodriguez, who is audibly Dylan-esque, Maier is not peerless, but this doesn’t make her bad. In 2013, with more people than ever striving to be successful artists, but with (as ever) only limited time, resources and room to do so, Maier, and the widening definition of what it means to be contemporary and even successful, heartens. That spinster-nanny with the Rolleiflex slung around her neck has done what she couldn’t in life: she has become au courant, a glamorous enigma. Through death and penury, she has made us smile.