Will Gill’s The Green Chair covered in ice on February 11, 2018. Courtesy www.townofelliston.ca. Photo: Neal Tucker.

Will Gill’s The Green Chair covered in ice on February 11, 2018. Courtesy www.townofelliston.ca. Photo: Neal Tucker.

On March mornings in Newfoundland, you often wake up to find everything shellacked in a thin layer of ice. The sky is low and grey (as it has been for days), and the wind is biting.

Yet there’s a hopefulness: by the end of April most of the snow will have melted and there will be at least a handful of days where you wake up to find spring sun drenching the bedroom in buttery light. This spring update from St. John’s looks at some recent work that deals with themes of cyclical destruction and rebirth in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Of Public Art and Ocean Ice

In the summer of 2017, St. John’s–based artist Will Gill anchored The Green Chair—a sculpture of a kitchen chair—to an outcrop of rock in the ocean near the rural community of Maberly. The piece was commissioned as part of the Bonavista Biennale, a new contemporary art festival that launched in August.

Gill based the sculpture on a wooden chair from a friend’s kitchen—the type of chair that can be found in many Newfoundland kitchens. He brought the found chair to Compass Manufacturing in Foxtrap, which created a steel replica that captured the intricate bevelling of each of the chair’s spindles. Gill painted the sculpture a chalky pastel green, a colour he choose because it is popular in rural Newfoundland and because it is a shade that sometimes appears in the crest of a wave just before it curls in on itself. Gill liked the idea of the chair simultaneously appearing completely out of place and mirroring the natural colours of the area—both a part of nature and something completely separate from it.

The isolated location Gill chose for the chair meant the installation process involved boxing the piece up and lowering it over a cliff with an improvised pulley system. Once the chair reached the ground, Gill and two assistants raced the incoming tide to secure the chair to a finger of rock where waves coming from opposing directions often crash against each other.

Speaking with Gill, I learn The Green Chair is about lifespans—he knew the piece would inevitably be destroyed by its interaction with nature, but he couldn’t know how long that would take. One day, he visited the chair and saw thick ribbons of seaweed wrapped around the legs. He was fascinated both by the beauty of the seaweed moving in the water and by his own awareness that the friction of its movement would be wearing on chair’s paint, contributing to its erosion.

In the months after the Bonavista Biennale ended, people continued travelling to Maberly to see the chair and photograph it—first, with frothy waves crashing over it, and more recently, shrouded in layers of ice. Gill created an Instagram account (@willgillthegreenchair) devoted to submitted images of chair.

In early March, the first sea ice of the season snapped the piece in half. Gill received a photo of the chair with the top ripped off and the spindles bent backward, clumps of ice surrounding the legs. The following day almost all of the chair had washed away.

Gill says that although the destruction of the chair felt like the satisfying completion of the piece, there was also something sad about it. It forced him acknowledge that he had secretly been hoping the chair might somehow survive the hundreds of pounds of spring sea ice that were pummelling it.

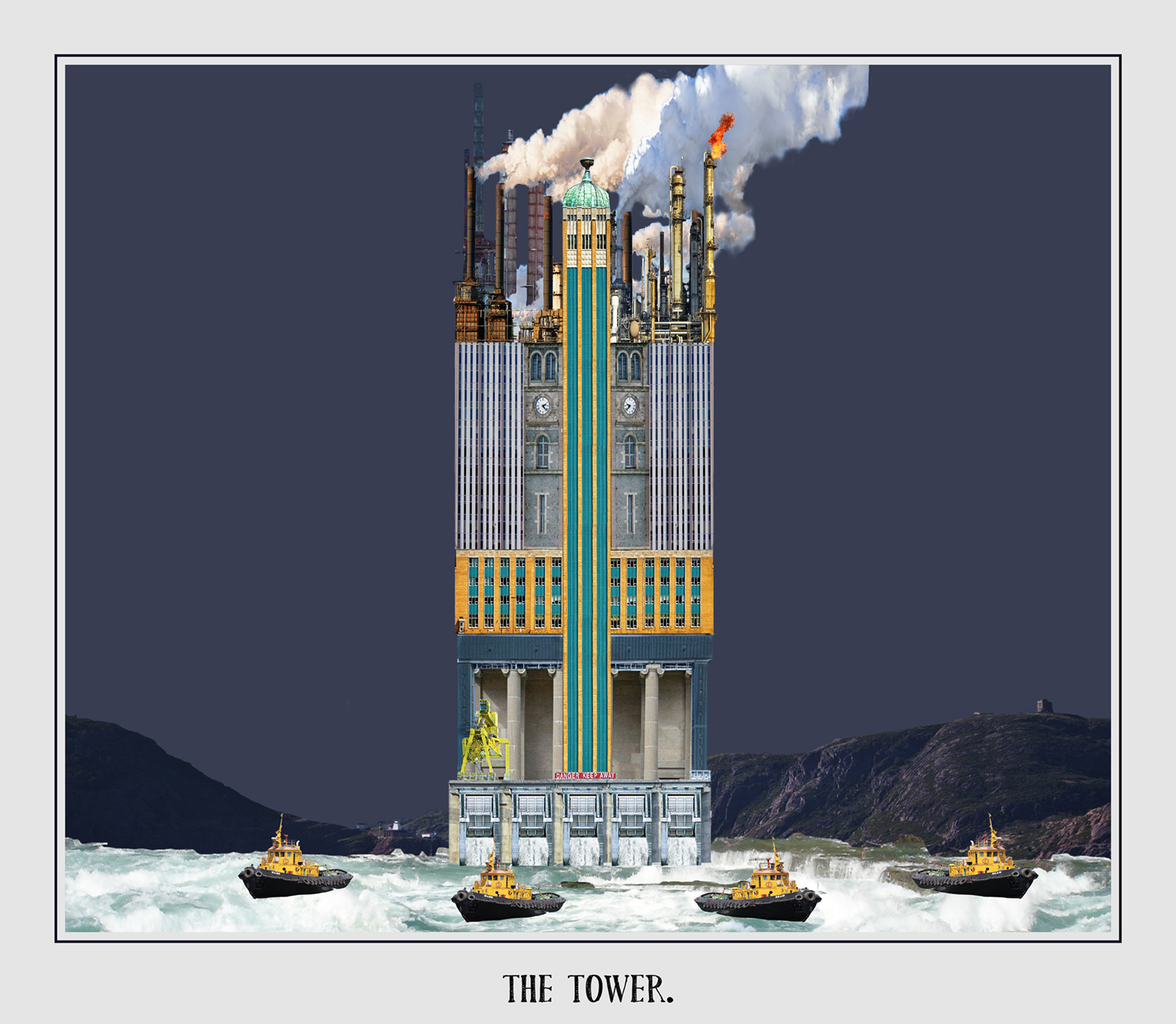

Rhonda Pelley, The Tower from the series The Fever, 2018. Digital photo-collage.

Rhonda Pelley, The Tower from the series The Fever, 2018. Digital photo-collage.

Divination from a Hydro Tarot’s Fools and Fortunes

If Will Gill’s Green Chair examines the cyclicity of life and death, as well as connections to unforgiving natural landscapes in Newfoundland, then Rhonda Pelley’s “The Fever”—which opened at the Rooms in January and runs until June—investigates cycles of provincial politics.

The exhibition is a collection of digitally collaged images that combine found archival photographs with Pelley’s own photography. Each image is an interpretation of a traditional tarot card; some of the cards are turned face up and others are face down, suggesting a reading that is still in progress. The cards that are turned face up reveal repetitive patterns in Newfoundland and Labrador’s history through dreamlike images that blur people and places together.

Pelley says “The Fever” was inspired by ongoing resistance to the construction of the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric dam in Labrador. The dam threatens to poison Lake Melville with methylmercury and flood surrounding communities, and the project is already widely acknowledged to be a financial disaster for the province.

In Pelley’s tarot deck, the Tower is a representation of the Muskrat Falls hydro dam. And the card depicts a distorted amalgamation of the St. John’s Confederation Building and Courthouse balanced on top of that dam. Four yellow boats float in tumultuous water below the dam, and the sky behind it is dark and ominous. In a document that accompanies the exhibition, Pelley points to the fact that the Tower card, in tarot, often expresses “the demolition of structures of ignorance and ambitions built on false reasoning.”

Rhonda Pelley, The Emperor from the series The Fever, 2018. Digital photo-collage.

Rhonda Pelley, The Emperor from the series The Fever, 2018. Digital photo-collage.

“The Fever” evokes a history in Newfoundland and Labrador of falling for charismatic provincial leaders and their doomed get-rich-quick schemes and legacy mega-projects. Pelley’s version of the Fool depicts a woman whose eyes are obscured by overlapping bills, a man’s arm in a business suit is stretched ahead of her; the hand clutches a cucumber. This card is a reference to past premier Brian Peckford’s failed multi-million dollar project the Sprung Greenhouse.

Like Muskrat Falls, the Sprung Greenhouse project was pitched as a miracle solution to the province’s lack of financial stability. The fancy hydroponic system was supposed to create jobs and provide affordable produce for people in the province. While the greenhouse did produce a huge number of cucumbers, the province failed to find a market for them and the project ended up costing taxpayers $22 million.

In many ways, Pelley’s tarot deck and its reading is a call to action that asks Newfoundlanders and Labradorians to examine our province’s history, in order to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Indigenous Art Reclaims Government House

This month, Mi’kmaq artist Jerry Evans curated “Reclamation,” a group exhibition of work by 27 Indigenous artists installed the province’s Government House. As part of the exhibition, which wrapped up this past weekend and was part of Eastern Edge’s Identify program, Evans removed a number of pieces of non-Indigenous art from Government House and replaced them with work by Indigenous artists who have a connection to the province. (In the installation image above, a painting by Jonathan Howse is hung to the right of a Government House’s portrait of the Queen.) If Pelley’s exhibition is warning against perpetually reliving past failures, Evans’s exhibition was beginning—and continuing—the work of actively ushering in a new era for the province.

“Reclamation” has hung in Government House for most of the Lieutenant Governor’s regularly scheduled events in April. According to Evans, the gesture of taking down non-Indigenous artwork and replacing it with work by Indigenous artists is a contribution to contemporary conversations about reconciliation in the context of ongoing oppression of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

In 1996, Evans curated a group exhibition titled “First,” which showcased contemporary works by 46 Indigenous artists from Newfoundland and Labrador. “Reclamation” features work by some of the artists who were part of the “First” exhibition and Evans says he was excited to hang their work alongside pieces by younger Indigenous artists who he views as “shining lights for the future of Indigenous art in the province.”

Those younger artists include Jordan Bennett, who was recently longlisted for the 2018 Sobey Art Award. His piece Our People, Our Tradition(All) Blanket hung just outside the door of the Lieutenant Governor’s office. In a statement about the blanket, Bennett explains that he uses the style of a traditional Newfoundland blanket (which displays a series of images that have become iconic to the province, with description below) to examine how different cultures relate to stereotypes about themselves. To that end, Our People, Our Tradition(All) Blanket depicts a series of stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. The top left corner of the blanket features a drawing of a man staring into the distance with an eagle in the sky behind him, and the words “The Wise Elder” written below. A square in the centre of the blanket shows a man with an open textbook in front of him tossing money in the air; the words below read “The Free Ride.” The combined effect of the 12 images on the blanket conveys a powerful message about inaccurate portrayals of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Meagan Musseau is another young and accomplished artist Evans celebrated in “Reclamation.” Her pieces George Musseau with a salmon on Maqtukwek (Humber River) and Niskamij (my grandfather) were hung together in the exhibition. The first piece is a black and white photograph from Musseau’s family collection; in it, a man stands on a rocky riverbank holding a fish that is almost half the length of his body. The piece that hung directly below it is brightly coloured, brick-stitch glass seabead pendant, with the shape of the pendant mirroring that of the large fish in the photograph above. Evans says he chose to hang the pieces together because, for him, both pieces are about Musseau’s connection to her grandfather.

Evans notes that some of the artists featured in “Reclamation” weren’t even born when he curated “First.” Although he admits there are many more artists he wishes he could have included, he sees the range and scope of the exhibition as an indication of progress made by Indigenous artists in the province—and of a brighter future for Indigenous art in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Will Gill’s The Green Chair covered in ice on February 11, 2018. Courtesy www.townofelliston.ca. Photo: Neal Tucker.

Will Gill’s The Green Chair covered in ice on February 11, 2018. Courtesy www.townofelliston.ca. Photo: Neal Tucker.