This spring in Ottawa marks an intriguing juxtaposition of the unexpected and the anticipated, with the arrival of both surprising exhibitions and long-awaited spaces. While the downtown core sees new art spaces open to the public, an artistic pillar in Hull continues to provoke thought.

More than a decade in the making, the new Ottawa Art Gallery brings a sense of abundance. Part of this is due to its new, larger space, and part of it is due to a profusion of art inside of its new galleries, spreading over three of the five floors of the building. Its inaugural exhibition “Àdisòkàmagan/Nous connaître un peu nous-mêmes/We’ll all become stories” fills the third and fourth stories (the second floor houses the historical Firestone collection).

“Àdisòkàmagan/Nous connaître un peu nous-mêmes/We’ll all become stories” is an ambitious project billed as a survey of “6,500 years of art making from the Ottawa-Gatineau region,” and it is divided into four sections: “Bridging,” “Bodies,” “Mapping,” and “Technologies.” Each part is notably diverse, with art of various media from artists ranging from those familiar to the area to those lesser known, encompassing a wide variety of backgrounds.

I visited the gallery on its opening weekend and I cannot understate how full to the brim with visitors it was—an inconvenience I was happy to contend with. Between the crowds, a few memorable works caught my eye.

In the “Mapping” section, Anishinaabe artist Barry Ace’s Nayaano-nibiimaang Gichigamlan: The Five Great Lakes (2016) features five honour blankets referencing traditional Anishinaabe stories for each lake, crafted from Hudson’s Bay Company blankets. Embellishments on the blankets by Ace—including beading, horse hair, copper and mountain-climbing rope—form flower motifs and iconography such as the Thunderbird. These honouring blankets signify both the colonization of and cultural endurance of the Anishinaabe peoples, peoples upon whose land Ottawa has been built, still unceded and unsurrendered.

In another room, Ottawa-based artist Anna Williams’s sculpture and audio installation Canada House (2016–17) displays bronze beavers surrounding a sort of nest or dam made up of resin-formed sticks, illuminated with an internal, glowing light. The work’s label accurately points out that, like us, beavers “build, dominate, and exploit their habitats for short-term gain.” Williams’ work effectively calls attention to the ways in which the Ottawa area has grown from rural to urban in a relatively short time-frame. So much of the city’s landscape has changed within the last 50 to 100 years—except we have built our nests and dams in ways far more destructive and enduring.

In other places in the exhibition, photographs and paintings depict Ottawa and the region in days long since past, illustrating its changing landscape and urban growth over the years.

The exhibition catalogue features a hefty and in-depth collection of information and reflection, with essays from curators, educators, artists and professors—including Carol Payne, Wanda Nanibush and Jonathan Shaughnessy— on the vast and intersectional cultural landscape of the city. The exhibition is exciting to see and represents a notable shift in the region towards celebrating its artistic impact on a grand scale.

However, while walking through the Ottawa Art Gallery’s various rooms, corridors and staircases—all of which had multiple works of art on display—I could understand anyone feeling overwhelmed by the sheer amount of work packed into the spaces. While this demonstrates an enthusiastic approach for a very wide-ranging inaugural exhibition, it also made me eager for exhibitions to come that will hopefully allow for more breathing room for contemplation in between works.

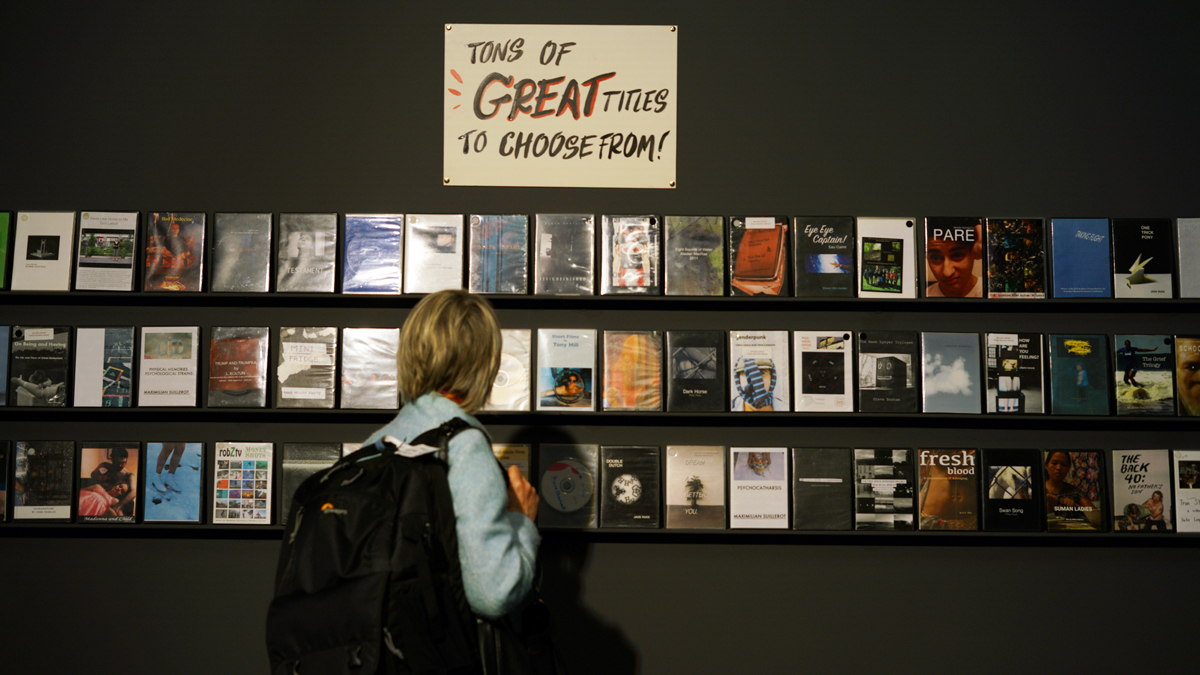

At Video Rental Store, a project created by the curatorial collective Under New Management, visitors can rent art video works on a barter or negotiation system, if they wish. Here is a view of the project at SAW Video in Ottawa. Photo: Mathieu Rioux.

At Video Rental Store, a project created by the curatorial collective Under New Management, visitors can rent art video works on a barter or negotiation system, if they wish. Here is a view of the project at SAW Video in Ottawa. Photo: Mathieu Rioux.

Following the second-floor connection to the old Arts Court (which the OAG previously occupied) reveals the new location of artist-run centre SAW Video and its modest and charming gallery, Knot Project Space. Its current project Video Rental Store, from curatorial collective Under New Management (Su-Ying Lee and Suzanne Carte), functions as an actual video rental store, stocked with DVDs available for rent. According to the exhibition text, the motivation for Video Rental Store lies in both tapping into the nostalgia of video rental stores and providing an opportunity for exclusively artist-made films to be available for rent with a “pay-what-you-wish with what-you-wish program.” Emphasis is placed upon creating a barrier-free direct channel to artists’ work by not requiring a membership fee or deposit. I saw one visitor/customer become elated as he found a film made by friends he used to work with at the Bytowne Cinema here in Ottawa, enthusiastically bringing it to the counter to check out.

The nostalgia continues with hand-written signs throughout denoting “No membership required,” “For a limited time only!” as well as an “Employees only” notice demarcating the area by the back desk. In another corner, a viewing station includes a vintage television and seating area for visitors to preview any film before deciding to rent it.

Another view of Video Rental Store, a project created by the curatorial collective Under New Management, at SAW Video in Ottawa. Photo: Mathieu Rioux.

Another view of Video Rental Store, a project created by the curatorial collective Under New Management, at SAW Video in Ottawa. Photo: Mathieu Rioux.

In the centre of the room, another stand holds more DVDs to peruse; in fact, that’s all there really is in this exhibition. There is nothing on the walls except for signs and shelves upon shelves of DVD covers, essentially forming a kind of mosaic in place of the artwork one expects to see.

The exhibition is well designed and installed, but its main success comes from its simple purpose and function, one well in line with the mandate of the centre—to support media artists in the community in a tangible way.

It’s also a risky project: basing the rentals on an honour system allows for the possibility of some artists’ work becoming lost. But, the curators are quick to point out in their text that a risk is also assumed from the viewer’s end. There is no instant gratification in this art project. Instead, viewers must gamble on a film, hoping they will enjoy it upon viewing at home. Unexpected and refreshing, the show both highlights local media art and effectively disperses it throughout the city.

A view of Skawennati’s exhibition “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

A view of Skawennati’s exhibition “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Over the bridge to Québec, another artist-run centre is presenting new media art.

One of Axenéo7’s current exhibitions features work by multimedia artist Skawennati, born in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory. Through installation, sculpture and video, “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” (also exhibited of late at Vox in Montreal), introduces a unique approach to tackling the subject of decolonization.

The Peacemaker Returns (2017), a machinima, was filmed “on location” in Second Life. “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” is billed as a children’s exhibition specifically for ages 5 to 11, and Peacemaker is a short film (just over 18 minutes) that tells a futuristic story set in 3025 wherein society lives happily under the three tenets of respect, unity and peace.

The narrator of The Peacemaker Returns, Iotenshèn:’en, tells of how Earth, in 3025, has recently become under attack by visitors, and so some have left the planet to live on a spaceship, free from conflict.

A dreamer, Iotenshèn:’e has a special power allowing her to see into the past. She recounts the story of the first Peacemaker who united five warring nations into the Haudenosaunee confederacy through kindness and respect. Then, she tells of how after a hundred years of good government, and advancements in science and the arts, Jacques Cartier arrived, placing a large cross on the ground and creating treaties that were never followed. Colonization takes a negative toll on both the peoples and the land.

It is then that the Peacemaker returns in the form of a baby girl who grows up to amass a large social media following used to spread her message of peace. The Peacemaker visits world leaders to affect change, ultimately meeting the President of the United States, where she exchanges her Twitter following for a promise to abolish injustice. The film ends with the narrator remarking that the next part is up to us: will we find and maintain peace?

A view of Skawennati’s exhibition “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

A view of Skawennati’s exhibition “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

The machinima is projected in a room within a large, arched installation of aluminum, Plexiglas and LED lights, a form resembling that of a longhouse. As mentioned in the film, the word “haudenosaunee” can be interpreted as “they make the house,” suggesting a structure where several nations come together as one. The titular gesture of extending the rafters, then, evokes a growing of the house and a welcoming of others into a community of peace.

At several points in the film, Iotenshèn:’e crafts wampum as symbols of the past and future. These wampum are displayed backlit on screens (like X-rays) to the left of the film and structure.

As an installation created specifically for school-age children, The Peacemaker Returns offers another perspective on the history and colonization of the land than that offered in most Canadian primary schools. It also sparks conversation about how viewers of all ages can best contribute to the peace of tomorrow.

Skawennati’s work is effective in terms of (re)framing the historical framework of colonization, conveying it from the perspective of some Indigenous peoples prior to the arrival of white settlers. Furthermore, by positioning the narrative from the future, and within a virtual environment, the story reels viewers in and stimulates their imaginations while also exploring very real and very present issues.

Manifested with a minimalist and futuristic aesthetic, “Teiakwanahstahsontéhra’/Nous tendons les perches/We extend the rafters” offers a compelling viewpoint on the past and provokes much thought about the future across all age groups. Notably, the title is an answer to its own question: How can we establish respect unity, and peace now and for the future? We can “extend the rafters.”

Rose Ekins is a curator, writer and arts professional based in Ottawa.

The new Ottawa Art Gallery attracted crowds during its opening week. Photo: Ottawa Art Gallery Facebook page.

The new Ottawa Art Gallery attracted crowds during its opening week. Photo: Ottawa Art Gallery Facebook page.