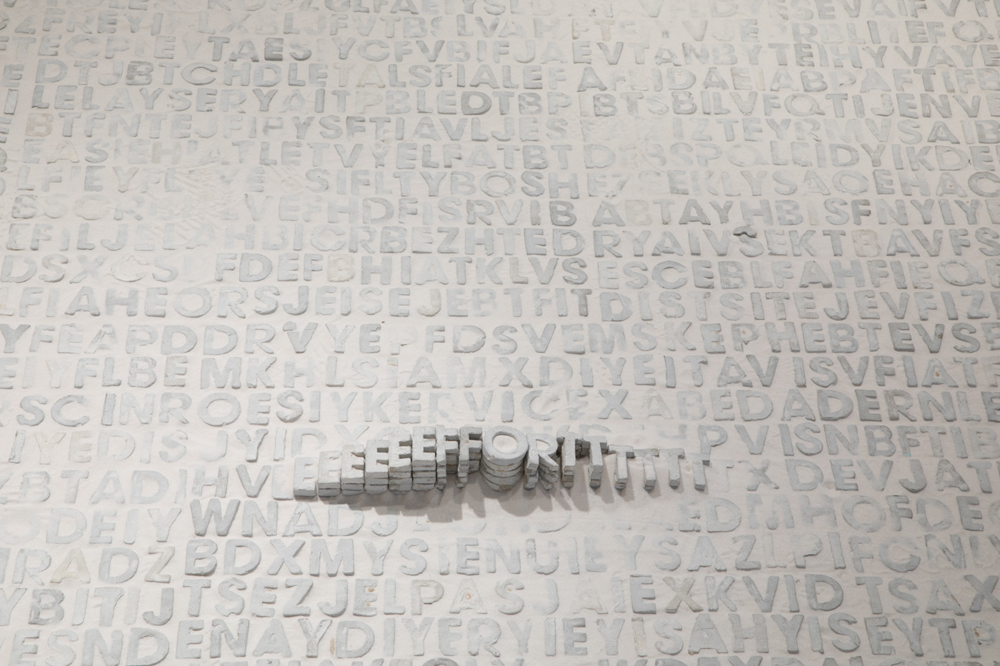

Christos Pantieras, “Am I Worth It?” (detail), 2017. Courtesy the artist.

Christos Pantieras, “Am I Worth It?” (detail), 2017. Courtesy the artist.

The Ottawa School of Art, located in a 1907 heritage building at 35 George Street in the Byward Market, opened 2018 with a solo exhibition of installation work by multi-disciplinary artist Christos Pantieras. “Am I Worth It?” which ran January 4 to February 4, transformed the school’s main gallery space to suit the artist’s floor-based artwork.

Upon entering the space, visitors were met with a wall and instructions to either remove or cover winter boots. After placing on the provided boot covers (much like those worn by crime-scene investigators on TV), I found my way along the wall, with the installation revealing itself on the right-hand side.

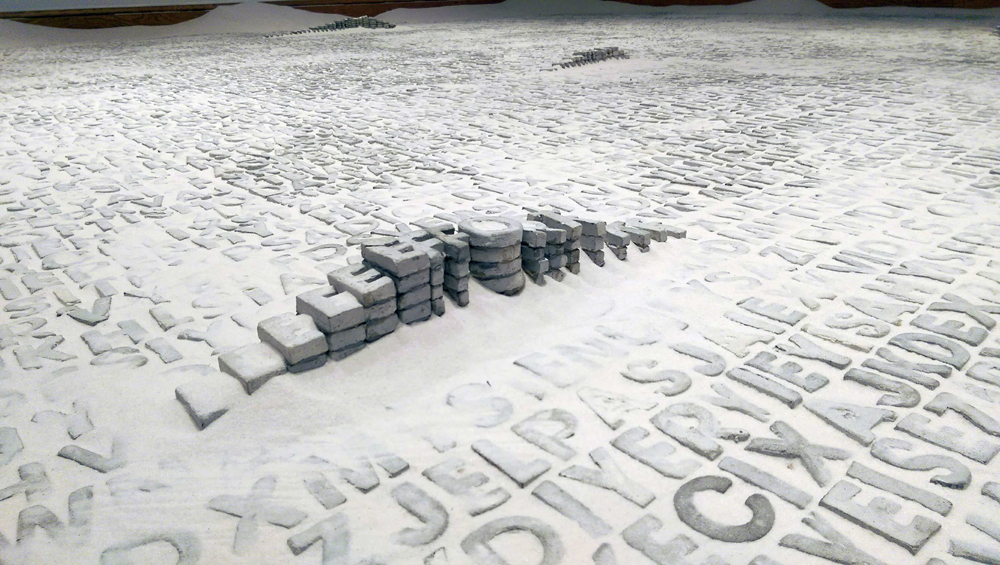

This clean, bright and well-lit room welcomed viewers into the space—and, notably, directly onto the art. The focus lay on the floor, where Pantieras sculpted letters and words, and dusted them over with sand that collected in crevices between letters, against walls and in corners. Visitors stepped onto the work and experienced the exhibition through a grounded, physical connection.

The Ottawa-based Pantieras holds an MFA in sculpture from York University. This most recent exhibition featured work previewed at Enriched Bread Artists, the biggest art studio co-op in the Ottawa region, located inside a former bread factory. (Pantieras is a member and studio holder there.) But it also felt customized for this space in particular, and this reflective time of year.

Christos Pantieras, “Am I Worth It?,” 2017. Installation view at Ottawa School of Art. Photo: Nina Camilleri.

Christos Pantieras, “Am I Worth It?,” 2017. Installation view at Ottawa School of Art. Photo: Nina Camilleri.

According to its accompanying essay written by Marie-Hélène Leblanc, the title “Am I Worth It?” connected directly to words on the floor which formed this sentence: “I’m not willing to make the effort.” This sentence was taken from an text message conversation Pantieras had many years ago, and the exhibition description states that the artist’s inbox is a source of the overall material for the installation.

The importance of the phrase “I’m not willing to make the effort” in this context is demonstrated via its repetition through the matrix of letters on the floor, and through added height. This repetition also reflects the lasting impression that a few words can make in an passing text exchange.

Pantieras’s simple, encapsulating design worked well—but of course, placing art on the floor runs the risk of it becoming obstructed, particularly with many viewers in the room at one time. Being in the space alone, I felt as if I had entered into, or rather overheard, another’s conversation. This peculiar invitation both required and resisted my interaction: I was welcomed, but solely as a spectator.

While the viewer could position themselves around and on these words, they were ultimately traversing a conversation that had already taken place. Pantieras’s work left me wondering whether the artist plans to continue with this style of installation, and how that could create dialogue with future visitors.

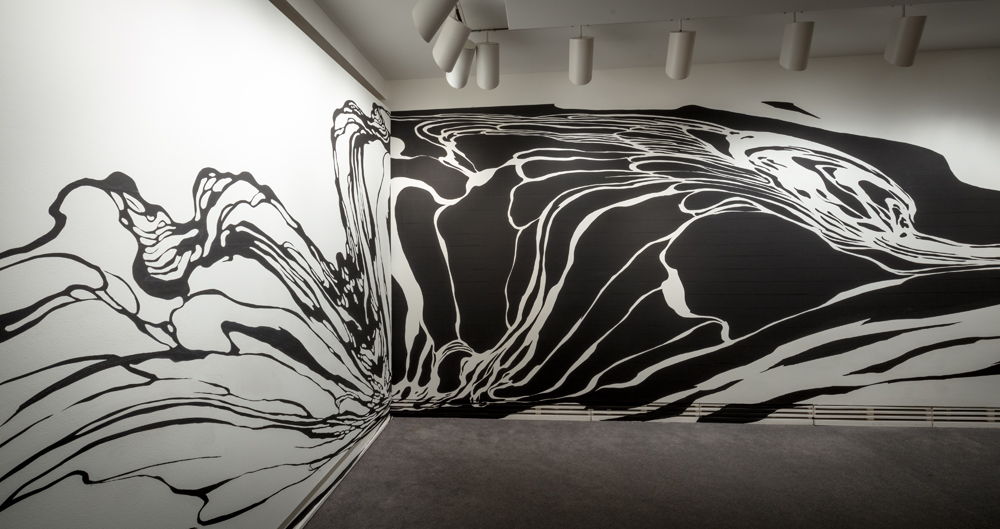

Sun K. Kwak, “Untying Space_CUAG,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Sun K. Kwak, “Untying Space_CUAG,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Across the city, two exhibitions on until April 29 at the Carleton University Art Gallery—Sun K. Kwak’s “Untying Space_CUAG” and Linda Sormin’s “Fierce Passengers” —also explore site-responsive installation.

“Untying Space_CUAG” marks the first Canadian solo exhibition for Korean-born, New York City–based artist Sun K. Kwak. In January, Kwak journeyed to Ottawa and spent a two-week residency with curator Euijung McGillis, creating and installing the work on the walls of the gallery’s mezzanine.

As with other works in Kwak’s “space drawing” series, “Untying Space_CUAG” involved adhering of black masking tape over walls, then cutting and forming these into rhythmic and linear shapes. These shapes vary in thickness, length and direction, making it appear as if large black strokes of black paint were brushed onto the wall, and applied into and over corners.

The continuity and formations of the lines in Kwak’s work manifest a striking sense of movement. Viewers, as they are drawn around the work, become responsive shapes too, fluctuating in their own formations around the artist’s shapes.

Sun K. Kwak, “Untying Space_CUAG,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Sun K. Kwak, “Untying Space_CUAG,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

One corner of Kwak’s installation sees an inverse monochromatic effect, where black lines become white and white become black. The artist told me that she sees the gallery (established in 1992) as a “space of contrast”—specifically, a place for representation of artists on the margins. As a result, this site-responsive piece might trigger some reflection on the CUAG’s own history of intriguing, thought-provoking programming—such as its years of exhibiting the work of Indigenous artists. In fact, the other exhibition on view at the gallery features drawings and paintings by Robert Houle (Saulteaux), whose first show at CUAG was more than 25 years ago, in 1992.

Kwak’s work requires a specific kind of maintenance: black masking tape does not always stay put. Curator McGillis (currently working on a Ph.D. in cultural mediation at Carleton’s Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Art and Culture) told me she assisted in the installation of the work and will maintain it throughout the length of the exhibition.

The inherent temporariness of Kwak’s installation, and its materials, helps foster a heightened sense of significance and singularity. Not only does Kwak create her space drawings differently each time she does them—whether in Brooklyn, Seoul, San Francisco and beyond—but her unique works, while requiring lengthy installation periods, are fleeting by their very nature. The location of Kwak’s work along the mezzanine, with its long white wall, functions well here—though she could certainly, as past works have indicated, fill a larger space. Supported by the Korean Cultural Centre, this Kwak exhibition will hopefully not be her last in Canada.

Linda Sormin, “Fierce Passengers,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Linda Sormin, “Fierce Passengers,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Down the stairs, Bangkok-born Canadian artist Linda Sormin’s “Fierce Passengers” is a vast site-responsive installation comprised of many elements: the artist’s sculptures old and new; projected slides; objects brought in by the public; and custom-built wooden ramps and structures.

Built over Sormin’s two-week residency at the gallery in January, “Fierce Passengers” consists of more than one hundred objects that, in some spots, fill the double-height room from floor to ceiling. It’s an ambitious project for this tall space, but a successful one, too.

Glancing around the expansive installation, one is able to identify a variety of objects: clay works of various shapes and sizes by the artist; donated objects like statues and vases; and tall, arched wooden beams. These beams, CUAG curator Heather Anderson told me, are intended to resemble the frames of a ship, the overall installation alluding to a dry dock where boats are built—and sometimes also taken apart.

A dry dock is a space for both human and mechanical production. Fittingly, some of the larger elements in this installation were lifted mechanically and rotated into position with direction from the artist, while wooden structures were hand-built to go underneath and secure the work in desired positions. It’s notable that these wooden structures, while maintaining structural integrity, intentionally create an illusion of precariousness: thin strips are used in peculiar formations and, in one section, what seems a vital support is actually suspended, floating above the floor.

Linda Sormin, “Fierce Passengers,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Linda Sormin, “Fierce Passengers,” 2018. Installation view at Carleton University Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

In another site-specific note, some of the installation elements are raw chunks of Leda clay, an unstable material that actually underlies much of the Ottawa region. Sormin’s slide projections, found in a secluded spot in the installation, focus on the crystalline structure of this clay, which turns to liquid when agitated or put under pressure—a phenomenon which has resulted in buildings in this city shifting, sinking and tilting over the years, particularly after earthquakes.

The shifting stories that lie beneath Ottawa’s sometimes-staid surface are of interest to the artist, too: during her residency, Sormin held an event where members of the public were invited to bring in personal objects for Sormin to include in the installation, specifically “objects that convey experiences of change and transition.” The resulting additions are compelling: one woman donated her hospital gown to the project, while other donations include ceramic versions of family tartans.

Narratives like these interact with and add to Sormin’s own shifting constructions. Wooden ramps (notably wheelchair accessible) form a path through the installation—and not only do the supporting wooden structures appear somewhat unlikely at times, but when I walked across the ramps I felt a great sense of my body’s own precariousness, and of its potentially devastating effect on this fragile environment. (This sense of danger was heightened by the gallery attendant’s reminders to all “passengers” of this “boat” to remove coats and bags before embarking.)

Each visitor’s journey through Linda Sormin’s “Fierce Passengers” installation, whether by donating objects or by traversing space, seems essential to Sormin’s effect: namely, creating a capacity for palpable interactivity in rapidly shifting spheres both great and small.

Rose Ekins is a curator and arts writer based in Ottawa.

Christos Pantieras, “Am I Worth It?” (detail), 2017. Courtesy the artist.

Christos Pantieras, “Am I Worth It?” (detail), 2017. Courtesy the artist.