It’s a vexed passion that binds humans to artworks. The former want experiences—or at least half-decent stories. But oftentimes, the latter just don’t want to play; they would rather be left alone to nurse their latent notions and neuroses. Still, the two need one another. Their unresolved union testifies to the importance of emotionally and aesthetically difficult art amidst so much pre-chewed spectacle.

Of course, generative difficulty is not the same thing as torment for its own sake. In love as in art, the two sometimes blur, and it’s this tangled state of affairs that was given salacious form in Emma LaMorte’s recent show at Stadium in Berlin. Befitting its fiendish title, the Canadian artist’s “Someone put a mouth in her sock and whited out her eyes” was a romantic tragedy wrought in harrowing pictures and intense writings. (It was also one of three exhibitions showing LaMorte’s work in Berlin inside a year, the next being a group show opening this week at Decad.) Far from withholding visual experience or narrative, LaMorte’s most recent show rendered both voluminously; its narrative portion operated less like the value-added content routinely slapped onto art with writing than the fictive guts churning within the exhibition itself.

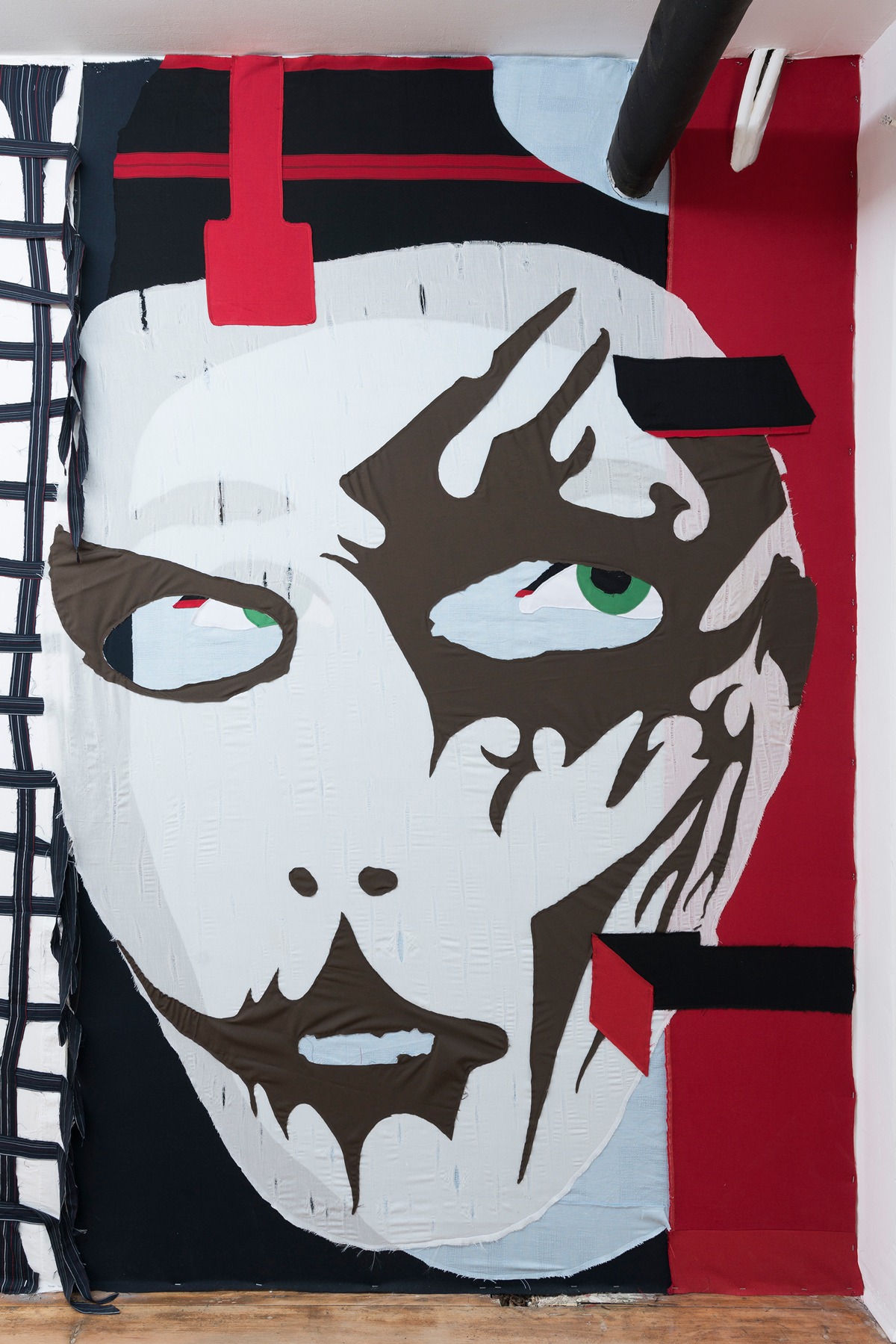

Transfiguring the gallery’s southernmost wall, four sewn tapestries housed colourful vignettes. Their patchwork language burns chromatically; in quasi-anarchic devolutions, their images melt into pattern. What we have here are fever dreams drifting between theatrical violence and some fantasy of cottage-industry art production. One scene has a snowbound cabin vignetted in a green ring and ink-stained fabric; one panel to the right, an ambiguous body appears, snared in royal-blue ropes; next comes a grey grid, broken and torn like an old insect screen; lastly, a black-and-white painted face, like those of Scandinavian death metal, barely obscuring a second green-eyed visage. Both faces are hemmed by red shards.

Emma LaMorte, Two-person games are fit for harsh climates like this Love, 2018. Textile collage, 140 x 220 cm.

Emma LaMorte, Two-person games are fit for harsh climates like this Love, 2018. Textile collage, 140 x 220 cm.

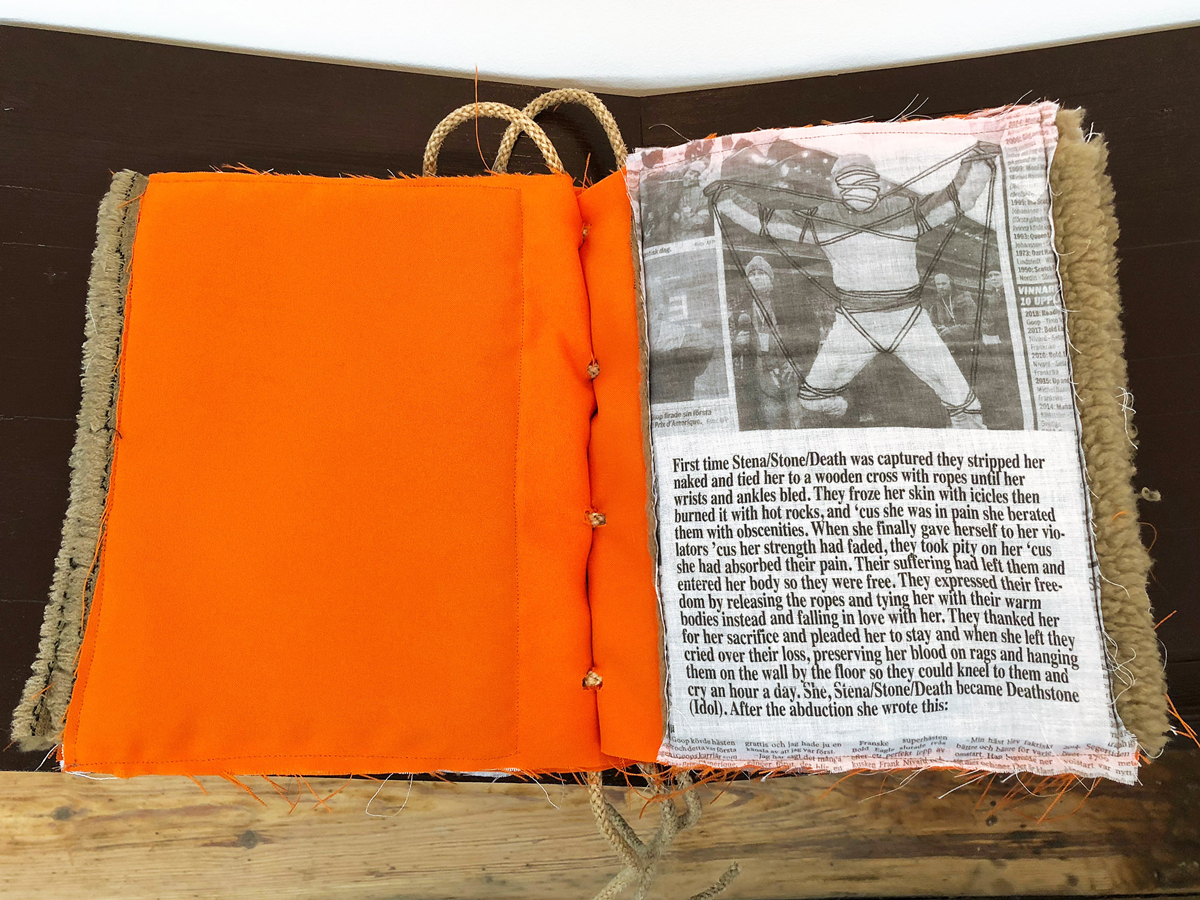

Is there fear in that second face? It’s hard to say. A story written by LaMorte doesn’t offer much clarification, as pain repeatedly morphs within it into the pleasure of the damned. Titled Stena and Älv, the fable unfolds within a handmade fabric book—reminiscent of some old tome constructed out of quilting samples by a Mennonite granny. Laser-printed onto pillowy orange pages, the words partake in a sparking counterpoint between disparate modes of production—modern printing technology, meet your antediluvian sibling. Here and there, the text is buttressed by photos. I remember a young man’s face, screaming and, again, made up like a black metal antihero or Kabuki actor. There is also an orange van submerged in snow; as the vehicle disappears into winter, text and image sink into the page. Such is the habit of ink deposited into fabric.

There are many tantalizing thematic threads to pull upon in this cloth book; most obviously, its cultural and political resonances. We begin in a war-torn and winter-bound city called Österund. Here, a dystopia has set in whose fictional cousins could be Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale or HBO’s Game of Thrones. The star-crossed lovers Stena and Älv have been exiled for the crime of un-coerced love, it having been decreed by the city’s regime that “love” be confined within rituals of abduction. What follows are epistolary accounts of torture—through burning and fondling—whose intonations oscillate between expected anguish and discomfiting affection. This is less the stuff of fantasy, it should be noted, than an extrapolation of the forced marriages many people still endure. And herein lies the show’s realism. The exhibition’s quasi-medieval visual trappings suggest that this plot might be echoing some monstrous past, but given the viciously conservative attitudes towards love and sex that are part and parcel of the resurgent right wing, the story also pulls disconcertingly towards a very unpleasant and very real future.

Emma LaMorte, Stena and Älv (detail), 2018.

Emma LaMorte, Stena and Älv (detail), 2018.

The gross spectre of dystopian fetishism lingers ominously near this kind of tale. But a perpetual and committed idiosyncrasy within LaMorte’s work defuses any risk that we might just be indulging in a catharsis made from stylized fascist tropes. Consider the words: we aren’t reading “a story about the ones who were abducted”—as conventional modern prose would have it—but “about them who were abducted” (italics mine). That “them” is an oddity. It echoes the syntax of a medieval storyteller—or at least an old pensioner playing one at the town carnival.

Such verbal tics invoke dark ages seeping into the present day. It’s a deceptively unsettling effect—one echoed in current political battles between social progressivism and neo-fascist politics (both in the form of official political parties and in the neo-Nazis who still skulk, pathetically, in cities like Berlin).

Unlike the usual desperate manoeuvres whereby text is used to shoehorn meaning into art, this cloth book’s positioning squarely within the exhibition (on a wooden lectern, no less) implicated the text in an active psychodrama. Performed halfheartedly, this arrangement could have been merely overwhelming. But in context, the book became both a literary and an actively sculptural entity. The writing’s nuanced formal relationship to the tapestries triggered an anxiety well-tuned with the story’s subjects—like the melody of a goth ballad churning under aching lyrics.

Emma LaMorte, Stena and Älv, 2018. Inkjet on textile, lectern, lamp, dimensions variable.

Emma LaMorte, Stena and Älv, 2018. Inkjet on textile, lectern, lamp, dimensions variable.

It has to be said that “Someone put a mouth…” gained almost too much from its host. Stadium’s low ceiling lent believability to the narrative of imprisonment; its wood-planked floor set the Old-World mood. But to be of any use, these architectural gifts had to be transformed. Protruding sections of the ceiling were flocked with squares of grey fabric imitating stone, and a floppy grid was hung over the space’s lone window—an old dungeon rendered as in high school theatre.

In its cartoonish aspects, LaMorte’s work has an ancestor in the German artist Cosima von Bonin’s patchwork paintings. But the genealogy of her method—art as some bastard camp theatre of props and backdrops—extends to America. In Mike Kelley’s iconic multi-channel video work Day is Done (2005), folklorish types—vampires, kabuki actors, neo-Nazis—are translated into the gaudy language of schoolhouse drama. Similarly, in LaMorte’s show, violent and fantastical themes flitted about at a misfit remove from their real-world references. Her tapestries recall the ritualized torture meted out in medieval European dungeons—or in Berlin fetish clubs last weekend.

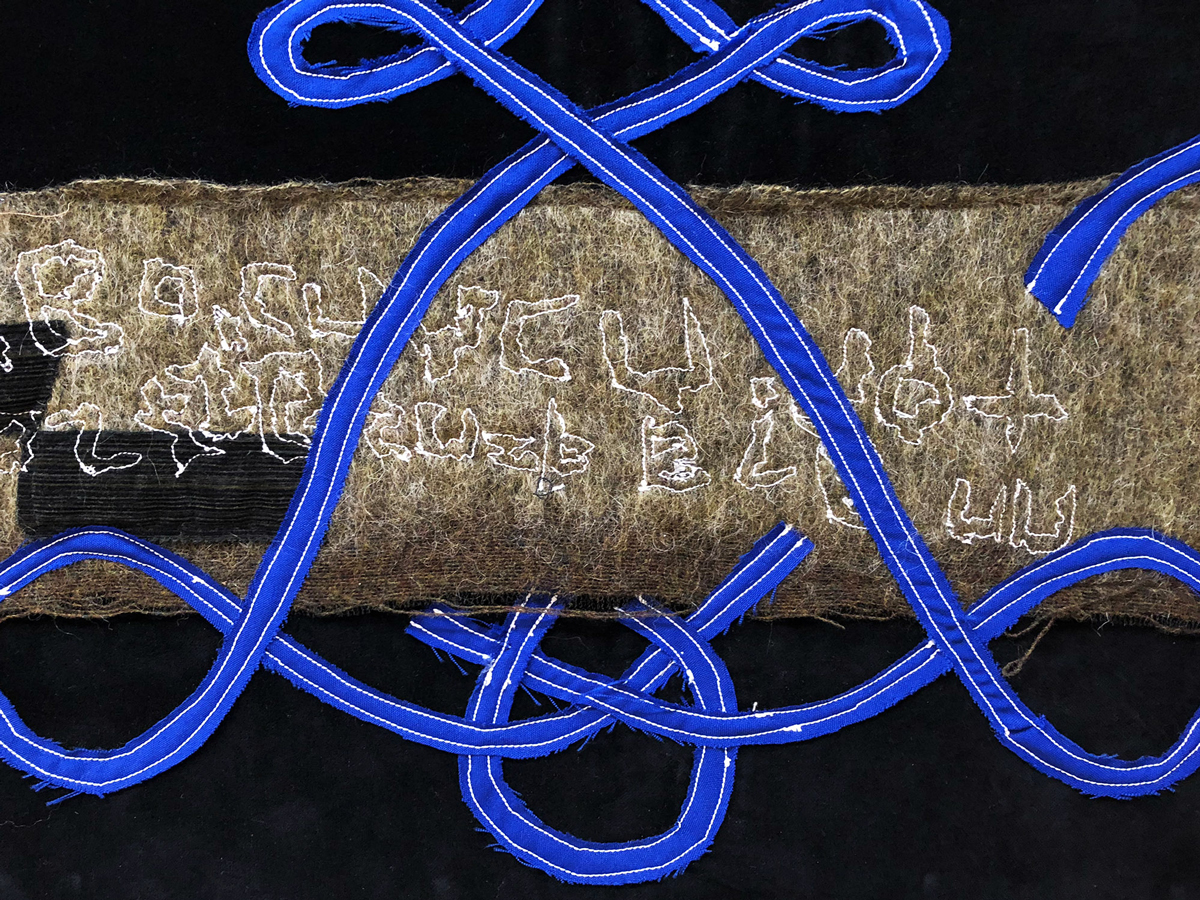

Never do we encounter these themes head-on; they’re always delivered through curious visual and haptic phenomena. The stitched blue lines depicting bondage rope in She, Stena/Stone/Death, became Deathstone (Idol) (2018) are rendered in blue fabric. As much as binding the human subject, these lines flood through the picture; analogous, maybe, to the way lashed skin might spread pain through the nervous system.

Emma LaMorte, She, Stena/Stone/Death, became Deathstone (Idol) (detail), 2018.

Emma LaMorte, She, Stena/Stone/Death, became Deathstone (Idol) (detail), 2018.

Everywhere, stitching is revealed like the static crackling in music. These are not gestures but techniques. They have nothing to do with academically well-behaved self-reflectivity. They just do what good art does: empower and challenge a viewer to experience the form through which a story is being offered. It’s like what Lydia Davis wrote of her predecessor Lucia Berlin: “This is the way we like to be, when we’re reading—using our brains, feeling our hearts beat.”

Innumerable stories of ill-fated love were threaded through the context of LaMorte’s recent show. Some are classic, while some are hackneyed but still oddly beautiful—Shakespeare’s doomed Veronese lovers mixing with Bruce Cockburn’s Lovers in a Dangerous Time. So how does an artist go about sucking fresh blood from this old vein? One answer provided by this show: impede the flow of clichés with languages that position the viewer in an active relationship to the story being told. This way, art and fiction become actually intimate, as readymade yarns are discarded for something painfully real.

Emma LaMorte, “Someone put a mouth in her sock and whited out her eyes,” 2018. Installation view at Stadium, Berlin.

Emma LaMorte, “Someone put a mouth in her sock and whited out her eyes,” 2018. Installation view at Stadium, Berlin.