In striking contrast to the cold steel of Brookfield Place, Tepkik’s vibrant Polysilk fabric sways in the air-conditioning gusts of the downtown Toronto office complex. Adorned with intricate designs and symbols, it is a site-specific sculptural work by Mi’kmaq artist Jordan Bennett, who has been shortlisted for the 2018 Sobey Art Award. Bennett draws inspiration from a petroglyph depicting the Milky Way that sits on the shores of Kejimkujik National Park in Nova Scotia. As a visual storyteller, he uses Mi’kmaq symbols to convey past, present and future understandings of his community’s ways of being. It began with multiple drawings influenced by Mi’kmaq porcupine quillwork. He enlarged two- or three-inch designs typically found on baskets created by his ancestors, to 127-foot-long banners. It’s a proud moment for him to tell these stories in this space as he brings to life these ancient, ageless designs from Mi’kmaq visual culture. I was fortunate to have a conversation with Jordan Bennett about his largest public artwork to date.

Adrienne Huard: Tell me about your process.

Jordan Bennett: As soon as I visited the space, this image came into my head. If you stand in the middle of the space, the image you see seems like a double helix, like a DNA string, but it’s a Mi’kmaq petroglyph found at Kejimkujik National Park depicting the Milky Way.

The piece is called Tepkik,which is one of the Mi’kmaq words for “night.” I wanted to bring this idea of “night” [in this space] all the time because outside of our planet, there’s always this forever continuation. Many of our creation stories come from there, and this piece is chock full of those symbols. And it’s not meant to be read in a linear fashion, much like Indigenous ways of being and time. You can start from any point and if you work your way from left, right, up, down, in, out, it’ll tell a different story.

The hanging banners, fan pieces and square motifs are on highly reflective road sign material—the same as highway signs—so when they’re lit, it just blasts. Each of these pieces are based on the Mi’kmaq Six Worlds. The stories from the Six Worlds each depict aspects of different levels of existence and creation. It was a lot of going back and forth between quillwork and canoe designs and petroglyphs.

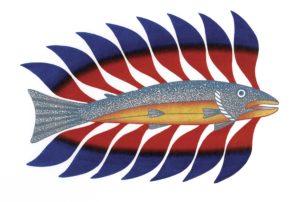

Jordan Bennett, Tepkik (detail), 2018. Site-specific installation. Courtesy Brookfield Place Toronto. Photo: Ernesto Di Stefano.

Jordan Bennett, Tepkik (detail), 2018. Site-specific installation. Courtesy Brookfield Place Toronto. Photo: Ernesto Di Stefano.

AH: I’m seeing seeing some symbols familiar to the petroglyphs at Kejimkujik National Park.

JB: I visited the site two weeks ago with Ursula Johnson, through her summer position at Parks Canada. She brought me, my wife, my mother, my father and my niece out to certain sites where only Mi’kmaq family and friends can go to visit. Ursula and I discussed who might’ve made these marks, and it would’ve been the women on the shores. A lot of the designs were in their clothing as signatures. My work retells the story of the coming of plants into Mi’kmaq creation stories.

Everyone asks why I use such bright colours but with Mi’kmaq people and our quillwork, the point of contact and colonization was so early that these very bright European dyes were used for quillwork. There’s hot pink as early as the late 1700s and everyone’s like, “Whoah, such hot pop colours.” But no, these are our traditional colours.

AH: I mean, look at our regalia.

JB: We didn’t mess around.

AH: I was really struck by this because you mentioned that you are inspired by these petroglyphs, and where I’m from, we have petroforms that have existed since time immemorial. Every time I visit Bannock Point in Manitoba, I’m really blown away. Tell me more about what your experience was like.

JB: Getting this personal introduction to the ancestors was very special because my family was with me. My mother and father were just absolutely ecstatic because they’ve seen me work on these designs for so long and they’ve seen other Mi’kmaq artists use them too.

I was nervous. These are our stories and a lot of them were passed on and a lot of them were written down—that’s how I got access to a lot of these. I’ve heard some stories from community members too but to go to this place and see the drawings first-hand is as close as possible as I could get to these people. Our big cities were trading places for all of our nations that came here so these stories were probably told in this exact same spot.

AH: This is off-topic, but has your life changed significantly since you were shortlisted for the 2018 Sobey Art Award?

JB: I wouldn’t say significantly. This was going on before I was even long-listed, but I’m really more of a quiet, stay-in-the-bush kind of person, so I don’t get the cities as much. But I’ve had a lot more people interested now that I’m on that list. It’s an amazing opportunity for people to recognize my work. And the cool thing about this installation is: I wasn’t chosen because I am Indigenous, because I fit a box. They were like, “Yeah we’ve seen your work and we really like it, and then we figured out that you’re Mi’kmaq.”

AH: My partner struggles with that because he makes music but he doesn’t want to be confined to a box. It’s hard to know where his place is as an Indigenous musician.

JB: It’s music and by chance, he’s Indigenous.

AH: Exactly. But I think it’s still possible to call yourself “Indigenous” first and “artist” second.

JB: Totally. And I go back and forth between the two. And we’re just moving out of that era, whereas, like, Daphne Odjig had to fight for that. If she didn’t, we wouldn’t be where we are now.

AH: Shout out to the ancestors.

JB: She was a big inspiration for me. I got to hang out with her a lot when I was in Kelowna. I went to visit her on her 95th birthday—my first job during my master’s was to help her Skype into a show. Daphne! At 95! So I’d go out to the senior home to help Daphne Odjig Skype in to Gallery Gevik [in Toronto] and we took to each other real quick. She was super sweet and I visited her weekly during the two years of my master’s. When I first met her, she was doing two 11 x 14 inch drawings a day, at 95. I was like, “If she can do that, I can do one a week.” So I started to draw again and then I started bringing my drawings to her and we started talking about art and different things. She’s in here. [Bennett points to Tepkik.]

Jordan Bennett, Tepkik (detail), 2018. Site-specific installation. Courtesy Brookfield Place Toronto. Photo: Ernesto Di Stefano.

Jordan Bennett, Tepkik (detail), 2018. Site-specific installation. Courtesy Brookfield Place Toronto. Photo: Ernesto Di Stefano.

AH: What’s next for you?

JB: Go home and have a nap. Then I’m doing another big public artwork for the City of Halifax at the Dartmouth Sportsplex, where I get to tell a Mi’kmaq story in Mi’kma’ki and the whole community will be able to see it. It’s a large sculptural form on a wall of printed glass running throughout the building, with all Mi’kmaq symbols.

AH: Taking back the territory.

JB: Yeah, one building at a time. I’m also working on a solo show for the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (AGNS), which opens December 1st, and there’s the Sobey show that opens on October 3rd. I’m developing a bunch of cool products for the AGNS show. I’m pulling designs from a lot of artists who did the work [before], and [since] the artists who made many of our old objects weren’t recorded—because they didn’t record the women’s names—the work is a way of seeing if anybody recognizes these symbols. When I did the same thing on a few murals in Nova Scotia and the community saw it on a large scale, they said, “Oh I recognize it, it’s from here. This is ours, this is our place.”

AH: That must be validating to be able to tell your own stories and for your community to recognize them.

JB: Yeah. I’m all about visiting. I like the idea that the longer you spend with a place, you learn more about it and about yourself. So in a way, I’m asking questions.

AH: Chi-miigwetch for sharing, Jordan.

Tepkik will be on display in the Allen Lambert Galleria at Brookfield Place Toronto until August 24th, 2018.

Jordan Bennett, Tepkik, 2018. Site-specific installation. Courtesy Brookfield Place Toronto. Photo: Ernesto Di Stefano.

Jordan Bennett, Tepkik, 2018. Site-specific installation. Courtesy Brookfield Place Toronto. Photo: Ernesto Di Stefano.