Feasting is an important tradition to many Indigenous communities. At the June 13 Art Gallery of Ontario opening for “Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulak”—the largest show of Inuit art in the AGO’s history—the Inuit curatorial team, honoured this tradition by serving seal meat that was harvested by a member of the Kinngait community in Nunavut. The curatorial team consists of five members: Koomuatuk (Kuzy) Curley, Taqralik Partridge, Jocelyn Piirainen, Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, Georgiana Uhlyarik, and Anna Hudson. In the words of multi-disciplinary artist and co-curator of the exhibition, Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory: “For Inuit, to share seal meat is to honour family and community. As Inuit curators, we wanted to honour Kenojuak and Timootee’s spirits and brilliance by doing what happens on kitchen floors, igloo floors, rocky shorelines and sea ice now and since time immemorial—by eating seal meat. For us, this is a symbol of unity and peace.” Shortly after Williamson Bathory was honoured for her ongoing contributions towards elevating Indigenous voices —she was named the recipient of the inaugural Kenojuak Ashevak Memorial Award, a biennial award supported by the Inuit Art Foundation—the seal was placed on the floor of Walker Court, while Inuit community members carved out pieces with their ulus and knives, and distributed the delicious fresh meat to guests.

As an Anishinaabekwe hailing from Treaty 1 territory, I understand that hunted game is not only integral to Indigenous sustainability, but an incredible gift. A harvested animal provides its body: for nourishment, ceremony, kinship and survival. It was the first time that I have attended a seal feast, and I consider myself very lucky to have been given that opportunity by my Inuit kin. It was admittedly strange at first, to participate in an Indigenous tradition in an art gallery, as these institutions have historically contributed to the colonial subjugation of Indigenous peoples and culture. However, this was an active approach in the process of decolonization and indigenization. The AGO created a safe space to honour the late Kenojuak Ashevak and Timootee (Tim) Pitsiulak.

After this context and reverence towards the artists, the culture and the community, it was time to venture to the artworks. The first half of the gallery space consists of the artworks of Ashevak. They’re immediately recognizable due to their design-like qualities, vibrant colour palettes and varieties of bird species. Known as the “grandmother of Inuit art” and a Companion of the Order of Canada, Ashevak used her artworks as a platform for storytelling and imagination. I was delighted to witness Ashevak’s famous stonecut print of the iconic bird, The Enchanted Owl (1960), and her different variations of the artwork.

The second half of the gallery is devoted to the works of Pitsiulak. These are contemporary representations of the Arctic, such as a heavy mechanical drill titled Canadrill (2015), a commentary on modern Inuit housing and the ongoing process of colonization in these communities, and on the realties of climate change. The medium of drawing has been passed down among generations of Inuit; however, Pitsiulak took on a new perspective by introducing intricate angles and muted tones in addition to his contemporary subject matter.

“Tunirrusiangit” is a strong step towards a resurgence of Indigenous artists, thinkers and makers. Displaying a collection of artworks by two prominent Inuit artists requires a continuing relationship to land and language, and consultation from the community. The AGO’s Inuit curatorial team has done this in a concise and reciprocal way, providing a caring and attentive opportunity to reflect on these influential artists.

Tunirrusiangit: Kenojuak Ashevak and Tim Pitsiulakis open from June 16th– August 12th, 2018. Admission is free.

Clarification was made to this article on June 25th, 2018. The updated article includes the names of all members of the curatorial team.

Tim Pitsiulak at Kinngait WBEC Studios, 2012. Courtesy Feheley Fine Arts.

![Kenojuak Ashevak, <em>Untitled [face with colour wings]</em>, 1966–1976. Felt-tip pen and ballpoint pen on paper, 12.9 x 16.8 cm overall. Collection the West Baffin.](https://canadianart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/E-14375-1024x768.jpg)

Kenojuak Ashevak, Untitled [face with colour wings], 1966–1976. Felt-tip pen and ballpoint pen on paper, 12.9 x 16.8 cm overall. Collection the West Baffin.

Tim Pitsiulak, Computer Generation, 2012. Coloured pencil, 50.8 x 66 cm. Collection RBC. © Estate of Tim Pitsiulak.

Kenojuak Ashevak, Bountiful Bird, 1986. Colour lithograph on paper, sheet: 58 x 77.6 cm. Gift of Samuel and Esther Sarick, Toronto, 2002. © Estate of Kenojuak Ashevak.

Artist Kenojuak and her two children exiting a tent, Cape Dorset, Nunavut © Library and Archives Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada.

Tim Pitsiulak, Canadrill, 2015. Black porous-point pen, coloured pencil, graphite on paper, Overall: 124.5 × 274.3 cm. Courtesy of the artist, 2016. © Estate of Tim Pitsiulak.

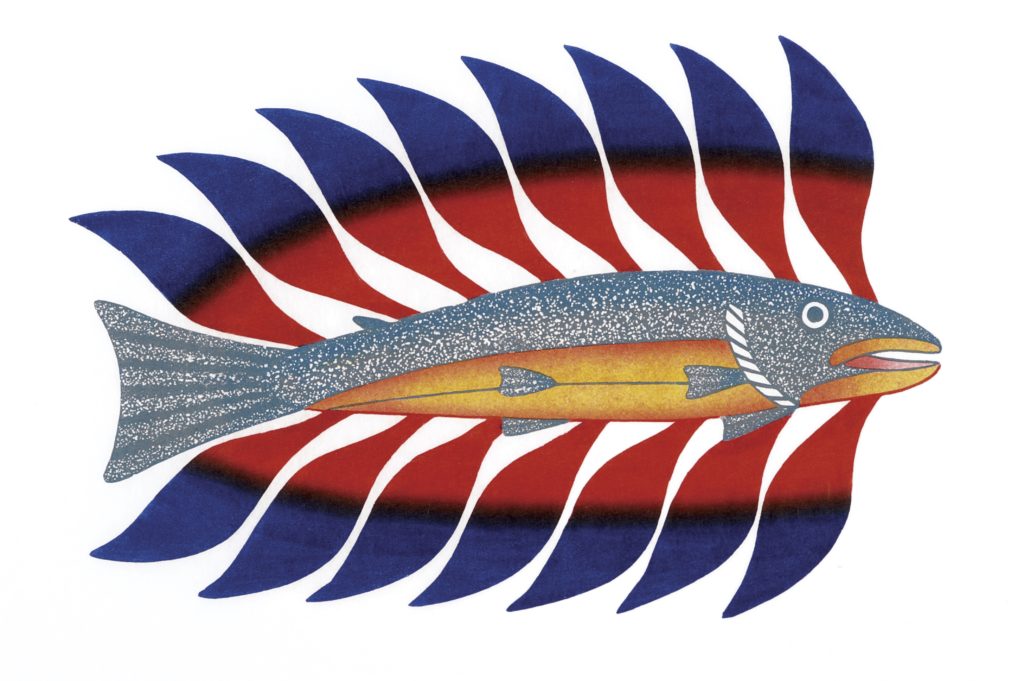

Kenojuak Ashevak, Luminous Char, 2008. Stonecut, stencil, 51.1 × 63.8 cm overall. Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts. © Estate of Kenojuak Ashevak.

Kenojuak Ashevak, Luminous Char, 2008. Stonecut, stencil, 51.1 × 63.8 cm overall. Courtesy Dorset Fine Arts. © Estate of Kenojuak Ashevak.