ANGEL CALLANDER

When HBO’s Chernobyl aired last year, I wanted to wait until I was emotionally ready to process it—whatever I thought that might be like. I started watching it on April 26th this year, without consciously registering that it was the anniversary of the explosion. I couldn’t tell you precisely what fleeting instinct prompted me to turn to it at that very moment. The series constantly invoked an aphorism that has been rattling around my brain recently: history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes (Mark Twain did not say this, by the way). Disputed statistics of illness and death rates, reluctance to heed the warnings of experts, withholding of information to maintain the illusion of power at the expense of actual lives, a heroic branding of civilian sacrifice—the political contours of crisis management started to seem eerily familiar.

I always love secrets, rabbit holes and a good conspiracy. It wouldn’t be right to say this pandemic has made me go dark; right now it’s more like I am compulsively trying to shield myself from historical amnesia. Kim Stanley Robinson recently wrote in The New Yorker that “There will be enormous pressure to forget this spring and go back to the old ways of experiencing life. And yet forgetting something this big never works.” I am banking on that last part.

There are a few books on the Cold War I’ve had sitting around that I’m now delving into. The legacies of soft power, misdirection and secrecy from the height of tensions between the Western and Eastern Blocs can still be found just about everywhere. And they become more pronounced in a time of crisis.

I’ve been reading Mark Fisher, because his absence is heartbreaking, and because his unique way of rescuing difficult concepts and explaining various relationships to power, especially regarding the aftershocks of Thatcherism, is very comforting to me. I think about his take on hauntology all the time. Besides, if there were ever a good time to start an 800-page collection of his writing, it’s probably now.

It’s not all serious, though. I made a blouse out of a tablecloth, a matching set from curtain fabric and a few masks with some scraps. I put together some audio mixes for the DJ in me that never was or will be (it’s actually a really soothing process). And I’ve gone back to watching The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, just to give my nervous system a jolt.

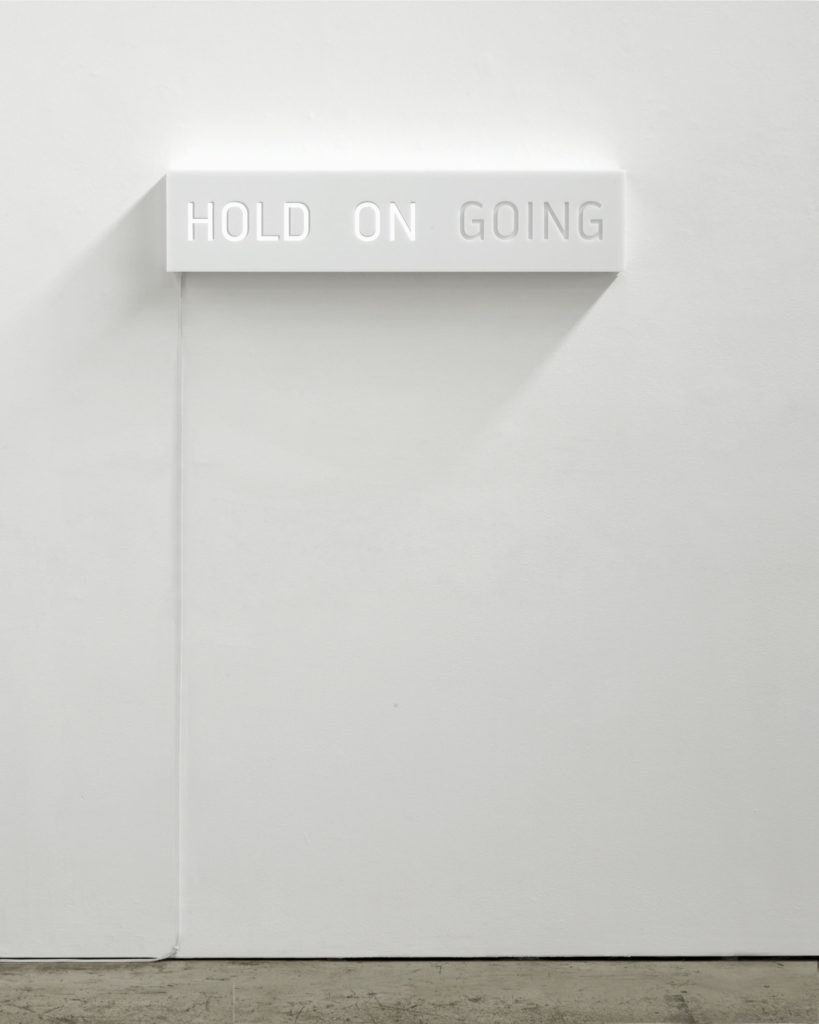

Lois Andison, hold on going, 2019. Acrylic, Arduino, LED lights, remote, 8 x 36 x 4.75 in. Courtesy the artist and Olga Korper Gallery. Photo: Michael Cullen.

Lois Andison, hold on going, 2019. Acrylic, Arduino, LED lights, remote, 8 x 36 x 4.75 in. Courtesy the artist and Olga Korper Gallery. Photo: Michael Cullen.

ERIN SAUNDERS

Big changes in language tend to follow big changes in the world, and it’s been fascinating to watch the speed at which new pandemic vocabularies have entered the lexicon. But I’ve also been thinking about some of the less obvious shifts in definitions and usage. Corporeal verbs—touch, hold, even see—now feel somewhat illicit. Intimate prepositions—with, between, among—are tinged with contagion. It reminds me that meanings are not replaced over time, but accumulated, and so often full of contradiction. I’m looking again at how Lois Andison’s light-based language works track these journeys of words from lonely objects to bigger, lonelier ideas. hold on going (2019), which slides between personal imperatives, indefinite states and definite ends with each pulse of light, is a poignant example, especially now as we all undertake to redefine even the most dependable of terms.

In addition to looking around more, I’m also looking back. I love etymology textbooks—they feel somehow safer than dictionaries right now—and have been spending time with my less portable ones. Their entries make every word feel like a character with a backstory. I’ve also been reading up on linguistics, with some effort (Gretchen McCullogh’s recent Because Internet has been a uniquely comprehensible read within a discipline notorious for its inaccessibility) and continue to come to terms with language as a messy improvisation rather than a set of unbreakable rules. Still, my books did not prepare me for last week’s family Zoom trivia night, this time actually themed on language and hosted by my word-nerd mother (needless to say, I did not win). Indeed, language may be instinctive, but it’s also hard.

I’m looking forward too, mostly by way of science fiction, because the real future is still so far away. At home (where else?) I’ve been watching a lot of Star Trek: Voyager; this one, which aired in the mid-’90s, is about Captain Kathryn Janeway’s starship, which is launched suddenly and unexpectedly into a distant, uncharted—that is, by humans—region of space. The crew’s predicament is not unlike our own: they must prioritize their safe return, to Earth and to normalcy, while trying to diplomatically and ethically document the unknown—not to mention find the words to describe it all.

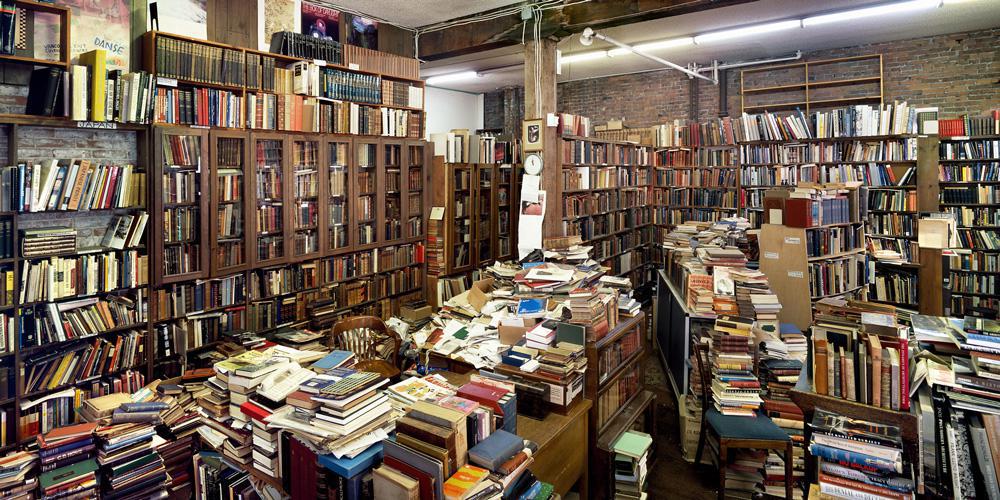

Stan Douglas, MacLeod's Books, Vancouver, 2006. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York, London, and Victoria Miro, London.

Stan Douglas, MacLeod's Books, Vancouver, 2006. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York, London, and Victoria Miro, London.

JAYNE WILKINSON

I can’t tell if it has been months or years, a few weeks or a season. The temporal ambiguity caused by mixing isolation with routine and worry with expectation is what makes the uncertainty of quarantine so destabilizing. Last month, I was preparing to move apartments and the physical and emotional work of packing, cleaning and purging was rewarded with persistent chaos. In an effort to quicken the restructuring of my space, I shelved hundreds of books and magazines with essentially no order—grouping them randomly, not by theme, design, author or artist. It inadvertently produced some strange bedfellows. I’ve been reading aimlessly across these newly proximate books ever since, relishing the promise of timely coincidence.

Some examples: I flipped to the first lines of Susan Sontag’s essay “Remembering Barthes” where she, writing just one week after Barthes’s death, recalled that he published his first book at age 37, “a tardy start.” (I note that I have not yet published a book.) I did finally start Don DeLillo’s White Noise, finding parallels with its slow time of imminent disaster (their toxic cloud, our invisible virus) and oppressive media atmosphere. The simply titled poems of Octavio Paz’s Configurations evoke quarantine through “Touch” or “Duration” or “Landscape.” John Berger’s collected essays in Landscapes brings one closer to the history of painting than any virtual museum tour. The title poem from Evelyn Lau’s Living Under Plastic is the most evocative of my coincidental impressions: “He spends his days reading, deciphering the code that will bring this planet back from the brink, admits it’s easy to love humanity when you live in isolation.”

After a week of fragmented reading, Anne Carson’s Float emerged, a collection of unfixed chapbooks designed to be read in any sequence. I barely get past the slipcover that announces, “Reading can be freefall.” Freefall must be what this moment feels like, grasping at meaning and finding simultaneity in the proximate and the distant. Quietude and slowness have entwined with panic and speed; we are ungrounded but maintaining velocity and direction as we find ways to build the world anew.

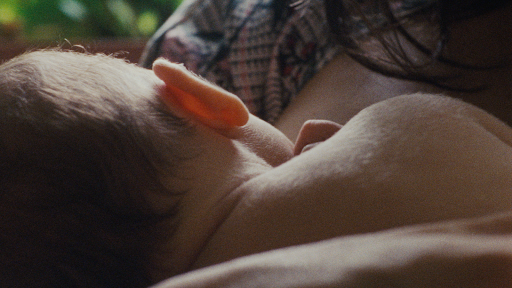

Kathleen Hepburn, Perfumed Dreaming (still), 2019. Film, 5 minutes, 22 seconds. Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board.

Kathleen Hepburn, Perfumed Dreaming (still), 2019. Film, 5 minutes, 22 seconds. Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board.

LEAH SANDALS

I’ve been admiring a lot of disability activist commentary lately—whether in the art world, as in this Akimblog post by Aislinn Thomas, or beyond it, as in this Nature piece by Ashley Shew. Tweets by Alice Wong, Imani Barbarin and Amanda Leduc highlight how what seems “new” to so many in the age of social distancing has long been an everyday condition for some folks with disabilities.

With the culture sector shifting (at last!) to online-accessible events—and because I’m privileged enough to have good internet and tech—I’ve been enjoying, from home, poetry readings I can’t usually get to because of childcare obligations, like the events streamed by the Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) in Brampton. I also, for various reasons, have found affecting the NFB’s short film Perfumed Dreaming.

But then there’s my need for escapism and comedy, which seems heightened. (And there’s more room for that given our reduced work hours too.) Lately I’ve watched The Mandalorian (Baby Yoda future nostalgia) and Sex Education (’90s/’70s retro set in the current moment). I’ve danced with my kid to Britney and Taylor and Katy, and gone back to watching Stephen Colbert. I’m reading old magazines, re-re-leafing the pages of a September 2019 Vanity Fair (which had a cover profile of Kristen Stewart by Durga Chew-Bose) like touch-smoothed runes.

To that latter point: I’ve been craving print and its materiality, its touchability. The May 2020 Toronto Life, about metropolis during pandemic, was one recent indulgence. Rummaging our own shelves: a pocket edition of Emily Dickinson’s short, sharp poems condenses; a Cody Caetano chapbook diverts. I’m also still loving the internet, though, when people do lovely or hilarious things like the #MetGalaChallenge, “Star Wars characters and how they make their coffee: a thread” or recreating famous paintings at home.

Other than that, well, is mood-disorder management a hobby? My regular psychiatrist appointments continue every two weeks, just over the phone. I take my meds. I’ve called my doctor a couple times. There’s a self-help group I attend online weekly, some YouTube yoga, a self-help reader. I write those last phrases with awareness that self-help isn’t what’s needed now, but mutual aid. There’s tension here: I find myself often, nowadays, simultaneously lonesome and withdrawn—aware of my privilege in being alive, of being safe enough to breathe and to feel, while also feeling apart. Or, perhaps, I feel lucky enough to be feeling apart, without falling apart.

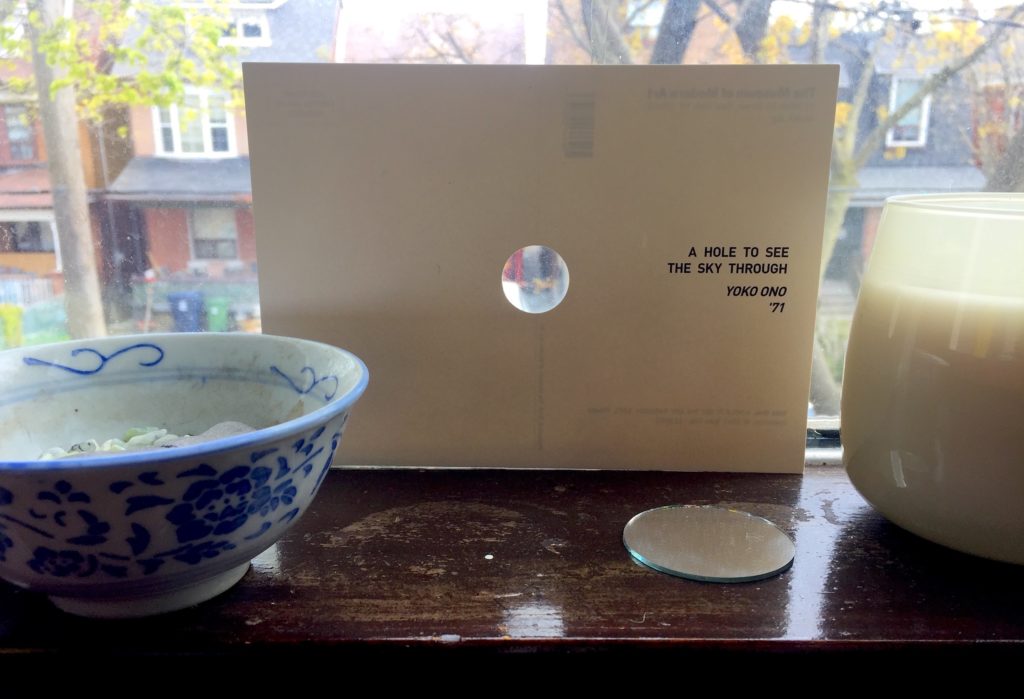

Courtesy Joy Xiang.

Courtesy Joy Xiang.

JOY XIANG

I’ve felt the rooms of my mind contract a bit and double down on the known world inside the house. Physical space feels both smaller and expansive, in the same energy as experiencing a global pandemic piecemealed into moment by moment. I’m growing green onions from their root nubs, planted inside empty Spam and soy sauce containers on the ledge in front of the kitchen sink. I’ve been learning the names of the houseplants, and depositing anxiety into observation by obsessively checking their moisture levels and exposure to sun, when I used to just leave them and hope for the best. Or assumed their survival.

I keep thinking of displaced meaning, and how images are changed by context; the images of our lives in the before times changes with the pandemic, “our” being a collection of individuals as well as the collective human and our faulty systems. I’m not a frontline worker so I’m at home most of the time, except for essentials. On my screen, a crisis is flattened, image by image, into news articles, opinion pieces, injustices shared on social media, Zoom meetings, friend calls and messages, virtual therapy, nights at the club while cooking or wanting to feel a semblance of common experience in spacetime. In the house there are my roommates and the cat we’re caring for, who’s like a sweet but insecure teen boy. Outside, more people stop to take pictures of spring flowers; masks hang in cars where air fresheners would be. None of this makes sense. While aspects of them have saved me, I can barely process art or music (Arthur Russell excluded). I’m not really reading and the things I’ve watched include hours of plant YouTubers, the Bon Appétit YouTube channel and Judge Mathis.

There’s a word I don’t remember until it’s useful: metonym, with the Greek root metonymia, meaning “a change of name.” It describes when a word is used to convey an idea or thing beyond its literal meanings—like how “ride” can refer to a car or “turning heads” refers to directed attention. That’s how it feels when reference to the pandemic as a whole, with all its webs, feels impossible. Similarly, is it possible for anything to not be related to the pandemic, and vice versa? What do images and daily experience, moment by moment, mean or give us? I’m unable to aestheticize anything right now—it’s a crisis, and maybe you are feeling this too. I’m spending a lot of waking hours taking a break from being mad or heartbroken. And maintaining sanity through the tangible things in front of me. Even if that’s the philodendron, the cat or dumpling dough that’s as soft as an earlobe.

Jenine Marsh, The cut flower still blooms, 2015. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Jenine Marsh, The cut flower still blooms, 2015. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.