As I started writing this series, the coronavirus was spreading and anti-Asian racism was intensifying, and I was thinking of ways for arts and culture workers to demonstrate solidarity. Part of what we can do is contribute to support systems for our communities, or at least start conversations on coping with racialized aggressions in this time of crisis.

I reached out to arts and culture workers and groups in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa and asked them to collect and share strategies for supporting each other, supporting businesses (especially those in Chinatowns) and supporting senior members of their communities, who may be more isolated.

I asked:

How would you suggest supporting, or how have you been supporting, your community in this difficult time? And what have you been doing to cope with social distancing protocols and prevailing (micro)aggressions?

I was overwhelmed by the amount of responses from colleagues from across the country, who are deeply involved in their communities. Here is the second instalment of this series of exchanges.

Morris Lum (photographer/artist, Toronto):

This is a difficult question because of the self-isolation that most of us are facing. This limits, to a certain extent, the amount of outreach that we can do, both as members of the Chinatown community and as artists. Part of the charm of Chinatown is being there and being an active participant in the community. With that said, there are certainly other ways of participating. The most obvious is through social media and making audiences aware of the current struggles of the tenants and businesses in Chinatown. This can be done by storytelling in the form of short videos, revisiting photo archives, poetry, illustrations. Part of keeping Chinatown alive is highlighting the importance of its history as well as its relevance to society as a whole.

I’ve been connecting with friends of the Chinese Canadian and Chinese American communities primarily through social media to listen and to share stories as we all deal with times of unrest and uncertainty. I find that sharing stories of common concerns helps to quantify the realities that we collectively face and strategize ways of facing them.

In my work, I’ve been sifting through my own archive to draw out narratives that I may have overlooked in the past and thinking about highlighting new stories or narratives.

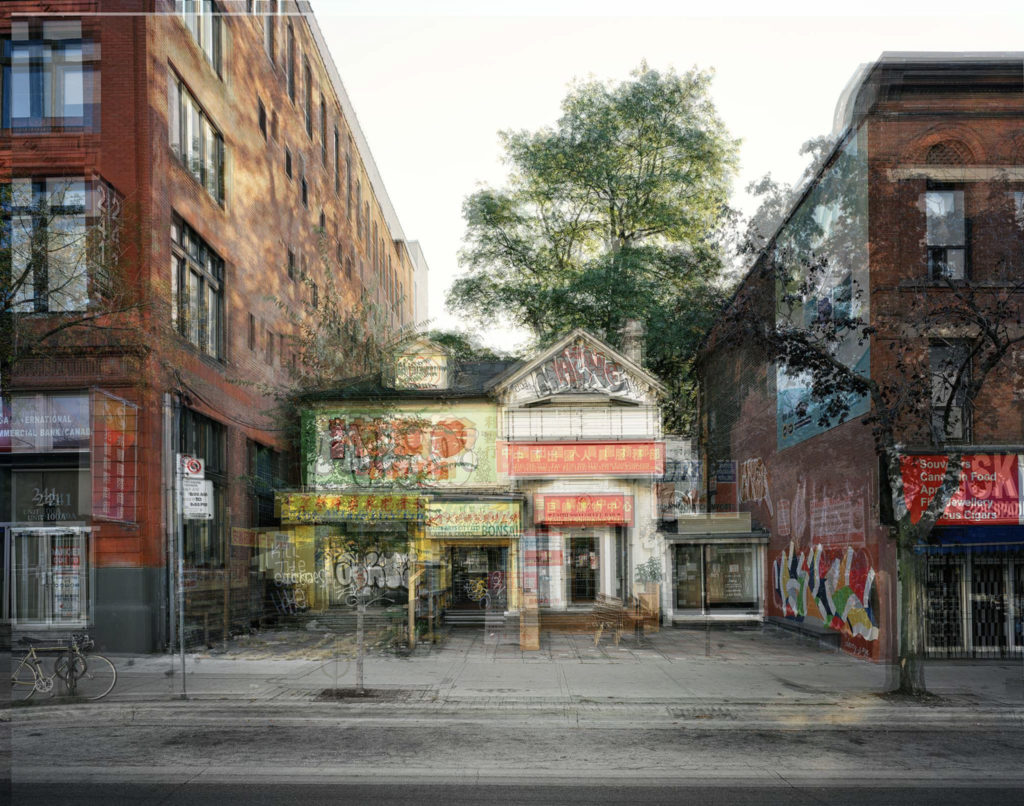

Morris Lum, 233-235 Spadina Ave from 2013, 2014, 2016, 2020. Archival pigment print, 102 x 127 cm.

Morris Lum, 233-235 Spadina Ave from 2013, 2014, 2016, 2020. Archival pigment print, 102 x 127 cm.

Karen Tam (artist and scholar, Montreal):

Here are some strategies:

1. Supporting local Chinese businesses: Restaurants: order take-out or delivery of meals for one’s household or for those who can’t go out; groceries and other stores: support through online ordering (but unfortunately not many businesses in—e.g., in Chinatown—will have an online presence or be set up for online shopping).

2. Supporting seniors: deliver hot meals; call them to check-in and have conversations to alleviate loneliness; and sew extra face masks for senior residences (as Mary Sui Yee Wong and others are already doing).

3. Supporting each other: call out racist incidents, acts or abuse for what they are, file reports and notify your local MP and anti-racist organizations to help compile a list of these incidents; and accompany individuals who do not feel safe or are anxious about being out alone while doing errands.

A friend and I are collaborating on a series of prints related to these racist incidents, and part of the proceeds will be donated to an anti-racism organization.

Like everyone else, I had to figure out ways of getting work done remotely (that is, away from the studio, especially in the beginning, as I was on a residency in Vancouver and did not have access to archival resources) and readjusting to cancelled and postponed exhibitions, residencies and other planned activities. Since returning home to Montreal, I’ve been self-isolating to make sure I didn’t pick up anything on the flight, at the airport, on the bus, etc. I am calling this time a “writing retreat” to catch up on projects and continue research from a distance.

Restaurant signs in Chinatown, Toronto, assuring customers of their hygiene standards during pandemic. Courtesy Shellie Zhang.

Restaurant signs in Chinatown, Toronto, assuring customers of their hygiene standards during pandemic. Courtesy Shellie Zhang.

Shellie Zhang, meme. Parallel forms of signalling that attempt to assure patrons of the establishment’s trustworthiness—a stigma that has surrounded Asian foods for generations.

Shellie Zhang, meme. Parallel forms of signalling that attempt to assure patrons of the establishment’s trustworthiness—a stigma that has surrounded Asian foods for generations.

Friends of Chinatown Toronto (FOCT):

We are a grassroots group composed of artists, architects, writers, journalists, business owners, residents and community activists fighting for community-controlled affordable housing, economic justice and racial justice in Toronto’s downtown Chinatown. Our group has compiled a list of resources in English, Chinese (Traditional and Simplified) and Vietnamese for those in the community affected by COVID-19. Resources include organizations and non-profits who are providing assistance with CERB (Canada Emergency Response Benefit) applications for Chinese speakers; free legal services for low-income non-English speakers; food banks and meals in the area; grocery support; crisis support for women and seniors; and reporting anti-Asian racism.

On May 21, Tea Base, FOCT and Butterfly: Asian and migrant sex workers support network coordinated a Digital Direct Action to support migrant workers affected by COVID-19. According to Butterfly’s survey, 40% of workers are excluded from financial relief and other social support programs by the government because of the criminalization of sex work, precarious immigration status and working conditions. During the action, workers shared testimonies and facilitators guided participants on effective ways of outreach and how to contact their political representatives. Details on how to support or donate to Butterfly can be found here. To stay up to date with FOCT’s actions and developments, follow us on social media or sign up for our newsletter.

Shellie Zhang (artist, Toronto):

Prior to the general population being concerned about the virus, xenophobic fears around COVID-19 were already impacting Chinatown and Asian spaces. Restaurants saw a drastic decline in business and were putting up signs that attested to their cleanliness in an effort to assure customers that they were safe places to dine. The same racist sentiments about uncleanness, untrustworthiness and otherness that have plagued Chinatown and East Asians for generations have been weaponized again. Even after social distancing subsides, these sentiments will continue to plague our communities.

We are simultaneously fighting longstanding racial and social injustices alongside the pandemic. Different communities have expressed concerns that they are being affected by COVID-19 in starkly different ways. There is such a direct correlation between those we care for now and how that care determines how we build our future. We must support our local businesses, our neighbours, our friends and strangers if we want to see them survive. Chinatowns have historically supported the working class, underserved, undocumented and hungry. It’s time we echo that history during this period of rebuilding.

Su-Ying Lee (curator, Toronto):

My suggestion is for non-Asian friends and community to listen to and believe what people are telling you about their experiences and feelings. Multiply that by the number of accounts that you don’t hear—because we are too saddened to talk about it, because it’s too common to bother mentioning, because we know we wouldn’t be understood, because we don’t share a common language to communicate with or even because we have internalized the racism—and that is the volume of incidents. What should be plainly understood is the reality that we in Canada live with. An underlying hostility and a crisis will be used as an opportunity for people to be openly vicious and exhibit hate. Please challenge, call out, call in and counter individuals who perpetuate racist ideas and all hateful ideas and biases.

Wet market in Shunde, China, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

Wet market in Shunde, China, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

I’ve been doing what everyone else has been doing to occupy time and keep connected. But I have also been more deeply considering an unrealized project that I have been thinking about for years. It involves opening a space in Chinatown and introducing new models for presentation and sustainability. During this time, new ideas for self-defined models, alternative economies, attention, retreat and ways being in relation to community—and thinking about where the boundaries of that are—are particularly present. I feel more driven toward this project each day.

And of course I’ve been dreaming of the artists and cultural producers I’d like to work with. Immersing yourself in the ideas within an artist’s work is an energizing way to pass time.

Listen attentively for information about how this pandemic affects all marginalized communities, near and far. Whose bodies are prioritized for care?

That said, I’d like everyone to retain the memory of this moment and understand that in reality, many groups of people face systemic, ongoing and deadly discrimination that will continue after we emerge. Listen attentively for information about how this pandemic affects all marginalized communities, near and far. Whose bodies are prioritized for care? Whose pre-existing social reality deepens their disadvantage and impedes their ability to survive at a time like this? Let’s think about how intersecting issues and identities can compound both privilege and disadvantage.

Think about disabled and chronically ill people for whom parts of this are an everyday reality and for whom ableism more intensely threatens their lives during the pandemic. Let’s come out of this challenging our own ableism. Let’s also think of the well-meaning expressions such as “take care of yourself” and “stay safe.” Those phrases imply choice and suggest that we are responsible for taking measures to guard against harm. Individuals can’t hold responsibility for the violence enacted against them due to the various social realities that make them targets.

Finally, a tumultuous mix of being racially Chinese and also immunocompromised during the COVID-19 pandemic keeps me further homebound. While I may be considered a threat by racists, I feel the double threat of potential contact with racism and infection.

Alvin Luong, Turbo (still), 2017-2018. Video (4K, 20 min), with 102 x 127 cm photographs and an official soundtrack. Turbo follows a teenage boy’s life after a car crash that coincides with the Great Recession 2007-2009.

Alvin Luong, Turbo (still), 2017-2018. Video (4K, 20 min), with 102 x 127 cm photographs and an official soundtrack. Turbo follows a teenage boy’s life after a car crash that coincides with the Great Recession 2007-2009.

Alvin Luong (artist, Toronto):

Help with translation if you can, like on the phone, for people who have language barriers to English or French. It is difficult to access government services, such as the CERB, now that there is no physical Service Canada to go to. It is important to note that while the government programs do help a vast majority, they also leave out many who don’t qualify, but also (more relevant here) is that some people, immigrants and newcomers, cannot access the services at all because of language barriers.

I have been keeping a routine, but also thinking of new ways to make work without space and mobility.

Henry Tsang (artist, Vancouver):

The antagonisms and blame fuelled by racism that have swelled certainly seem to be the zeitgeist these days, spurred by “leaders” to the south, back east and in many other places. But it’s mainly through social and regular media that I have experienced this because, like most others, I’m at home unless shopping for food or taking a walk.

Maggie Cheung in my bedroom. Courtesy Annie Wong.

Maggie Cheung in my bedroom. Courtesy Annie Wong.

Annie Wong (writer and artist, Toronto):

I live in artist housing, where a few of us are coordinating rent-relief and mutual-aid efforts as many of us face a precipitous loss of income. Social distancing has made it very challenging to organize but we manage by running a Zoom tenant hotline, slipping letters under doors and sending out tons of heart emojis.

As a social-practice artist practicing social distancing, I’m resisting any kind of work related to artistic production to care for my friends, community, loved ones and myself. My days are spent on new rituals of care that involve sharing as much as receiving all the strange dreams and desires, fears and anxieties that self-isolation has stirred in us. After midnight, if I’m restless, I’ll stream In the Mood for Love in the background to fill the room with Cantonese and fall asleep.

A couple of friends sent me an old poem I wrote a while ago that they’ve revisited in this context as either premonition, promise or a strange sense of place. I’ll share an excerpt here:

I want all production of capital and labour

To come to a devastating halt

And collapse at the threshold of your bedroom

Where we are sitting around

doing nothing

caring for each other.

*

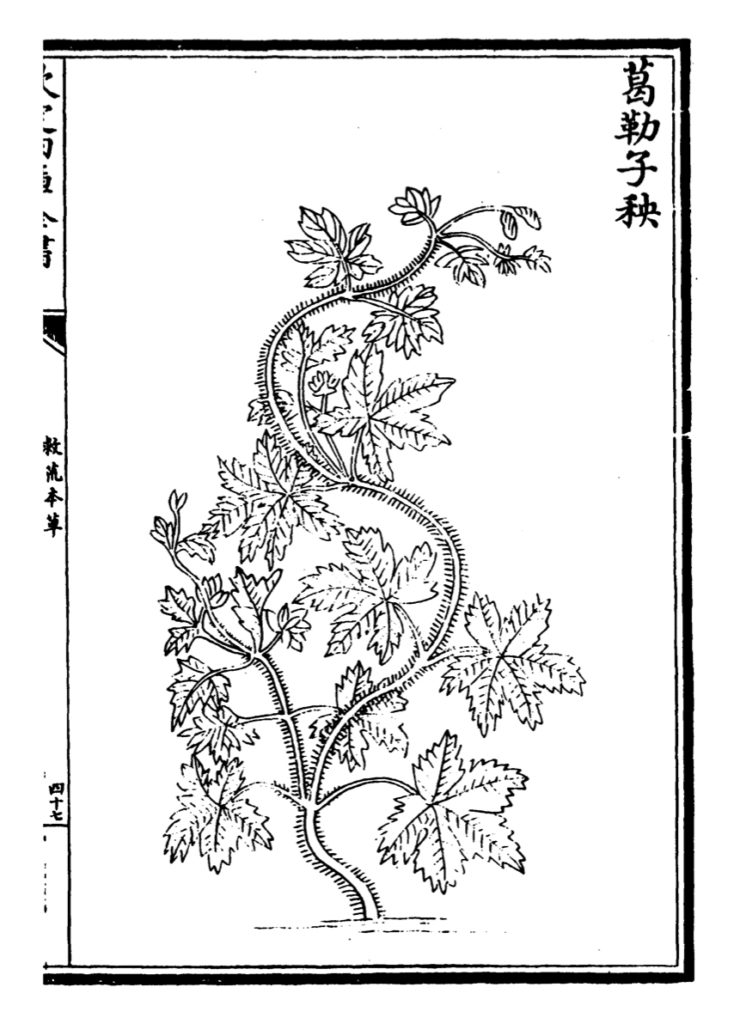

A page from the Jiùhuāng běncǎo / 救荒本草 (1406) by Ming Dynasty prince Zhu Xiao/Su / 朱橚, credited as the first illustrated botanical manual for famine foods (wild food plants that can be eaten for survival during times of scarcity). Courtesy Su-Ying Lee.

A page from the Jiùhuāng běncǎo / 救荒本草 (1406) by Ming Dynasty prince Zhu Xiao/Su / 朱橚, credited as the first illustrated botanical manual for famine foods (wild food plants that can be eaten for survival during times of scarcity). Courtesy Su-Ying Lee.

HENRY HENG LU—

Until speaking with these members of our communities and finishing composing this text, I was still trying to figure out how I should feel about or respond to the pandemic, and subsequently how to digest its impacts on our communities, my family, friends, colleagues and myself. Like what artist Paul Wong said in a recent phone call of ours: “This is not normal… We try to be normal but it is really not. Too much, too soon. Physical contact is being dehumanized.” This is a collective, traumatic time we are living through. And a lot of us have the ability and privilege of accessing things online. Rather than normalizing what is going on, maybe we can make a clean breast of our anxieties, anger, fears and hope in stride.

Social distancing is a privilege, and it has kept us apart physically. We therefore need to be connected more than ever. We need to support each other during this crisis and after it is over. And when we do that, we will be fine.

At my workstation at home, there are a dozen pictures I took of my friends at my birthday parties, favourite spots of the city in the summer and family enjoying meals together. They are wonderfully evocative of the pre-pandemic days, when hand scrubbing was not something that would be written on billboards or heard on radio stations on loop. It may take us a long time to go back to “normal,” but hopefully we will gain more empathy and compassion on our way there, a place where we can be free of the fears of each other and “the other.”

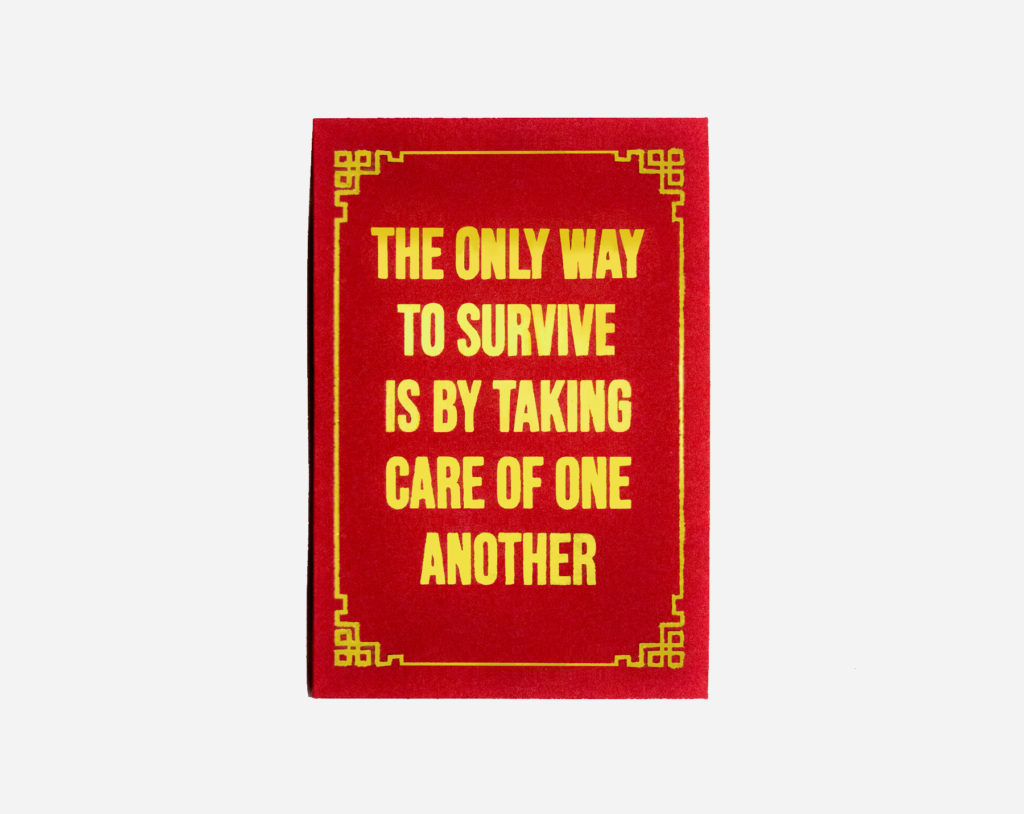

Shellie Zhang, The Only Way to Survive, 2019. Foil-printed paper envelope, 10.2 x 8.9 cm. Made for the Red Envelope Project, a collaboration with Alvin Luong, involving eleven artists in a fundraising initiative for Native Women in the Arts.

Shellie Zhang, The Only Way to Survive, 2019. Foil-printed paper envelope, 10.2 x 8.9 cm. Made for the Red Envelope Project, a collaboration with Alvin Luong, involving eleven artists in a fundraising initiative for Native Women in the Arts.