This morning I sat at my kitchen table reading the newspaper as I usually do and suddenly tears came to my eyes. I was crying for us—humans. Not out of fear or panic, but as I read the toll this virus was exacting on the world, the only response was to weep—for us, for the world and all the miraculous and astonishing life it contains. There is no doubt that this virus is a corrective of some sort, and I’m hoping that out of this will come some changes that will relieve the intolerable pressure we humans have been putting on this beautiful planet of ours. Nor do I doubt that this is a game changer—what the world will look like after this is anyone’s guess.

I think of the catastrophe of what living in a refugee camp must be, or being drowned at sea trying to make a better life somewhere else, or having your children taken from you and caged in the bosom of the heartland of democracy.

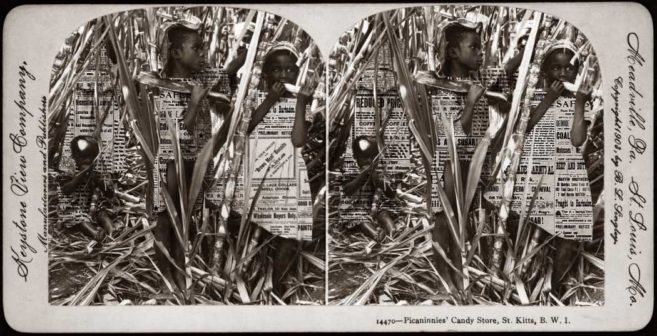

At times like this it’s easy to use the adjective “biblical” to describe these types of catastrophes, but my mind turned instead to what it must have been like for my ancestors who were brought here to this not-so-new world. I wondered who those “original” ancestors were that boarded the ship at anchor in some harbour along the west coast of Africa. Were they children? As they are children today, without parents, in the refugee camps in parts of the world we don’t visit as tourists. Were they men or women? Or both—a vibrant young woman perhaps, a strong young man? I think of the journey they would have made across the Atlantic—I think of that journey and also think of the journeys too many are making today, fleeing across borders, be they in the so-called Old World replete with old problems, gussied up in new clothing, or in the “new” Old World of the Americas. I think of what a catastrophe that journey would have been for them—continuing the catastrophe of being caught and sold, and perhaps bought again only to be held in the stinking slave fort before shipment. I cannot imagine the horrific crossing in the hold of a slave ship, but I think of it and of the continuing catastrophe of enslaved life on a plantation somewhere in the Americas or the Caribbean. Oh, I think of the catastrophe upon catastrophe of being sold off or seeing your loved ones sold off as I think of the catastrophic life that far too many of our brothers and sisters live today—they are our brothers and sisters under the skin—living with uncertainty as we do now, living with the terror of daily bombings, living with being maimed or seeing their loved ones maimed. Living with daily deaths. I think of the catastrophe of what living in a refugee camp must be, or being drowned at sea trying to make a better life somewhere else, or having your children taken from you and caged in the bosom of the heartland of democracy and wonder if we will have more compassion for those strangers who are now our kith and kin in catastrophe—and yet ours is still a far gentler catastrophe—to date, at least. There is toilet paper, after all. And running water. And health systems, albeit over-taxed.

The tears have now dried on my face, the paper lies open on the table before me: I think of the COVID-19 virus, invisible to the naked eye, which has wreaked such havoc in such an achingly short time, and see the parallel with another virus, albeit metaphorical—the virus of greed that spawned that earlier global disruption and destruction of nations, peoples and cultures. Indeed, it uprooted the world as it was then. We can call it colonialism, imperialism or whatever we care to, but like COVID-19 it has penetrated our lives as it did the lives of our ancestors and left in its wake a plethora of ills—racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia—the bedrock of our catastrophic lives today. Many of us, like the scientists tasked with finding a vaccine against this most recent illness, have been working overtime to inoculate the world against these ills, to return us to some semblance of—normalcy? Stability? My thoughts break against the impossibility of the meaning of those words as my mind turns once again to those unknown, unnamed ancestors: I wonder at the fact that they survived that extended catastrophe which reaches into my present and which also brought them unwilling to this part of the world. But here is my hand—resting on the newspaper—and I am filled with a fierce joy. And wonder. I am alive! Because of them I am. Here. Now. And knowing that—knowing that I am the evidence of their surviving that particular set of catastrophes—shores me up as nothing else in these catastrophic Covidian times.

This essay is adapted from a public post made by the author on March 18, 2020.

Stan Douglas, Doppelgänger (still), 2019. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

Stan Douglas, Doppelgänger (still), 2019. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.