In early March, I received a message on WeChat from my mother: “Be careful. Avoid people who are aggressive.” I thought to myself, “I do that in general anyway.” I didn’t know then that she had heard witness accounts of racist attacks toward someone she knew, and that that had made her concerned about my safety. And then COVID-19 blew up in Canada.

As COVID-19 continues to spread across the country, a renewed wave of anti-Asian sentiments with a strong likeness to “yellow peril” is evidenced by attacks on, and fear toward, Asian (Canadian) communities. An internet search will bring you numerous reported incidents, most commonly physical attacks and vandalism, let alone the unreported ones. Being Chinese myself, like many friends, I was afraid of wearing masks in public when the virus reached closer. In a time when people are hyper alert, wearing a mask while “Asian” invites extra suspicions; coughing while “Asian” can bring more than just eye rolls. At this point, as long as you look “Asian”, you are likely to be targeted and you likely feel like you need to be more cautious.

I work in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Before our gallery closed to the public, I had witnessed the gradual decrease of foot and car traffic. Our neighbours—restaurants, bakeries, grocery stores and so on—suspended dine-in services overnight and some closed altogether. I went to the post office to mail exhibition invitations and then to my regular joint for take-out lunch; I visited a nearby cafe for my daily dose of coffee; I even did some banking before work. And then, suddenly, Chinatown became static. On top of this was the everlasting gentrification: Chinatown was already suffering before the pandemic. Now what about those who need assistance with simply getting groceries? What about those who do not have a bank account and cannot speak English, or who are with minimal or no mobility and need constant care? There are many, many people in the neighbourhood facing obstacles every day, people who are forgotten and left behind.

In Chinatown, I hold dear this sense of neighbourhood in which a lot of people who look like me find comfort and support themselves in their own ways. We all benefit from neighbourhoods like these: “cultural” clusters where you can do things for cheap (as if to some, “cheap” is their branding). When you want to get your phone screen replaced, your friend might tell you to go to Chinatown. When you want “ethnic” snacks, you might go to one of those family-run grocery stores with fresh produce laid out at the entrance. When you miss home (or want an “Asian” experience), you could walk into a dim sum restaurant with waitresses pushing steel carts full of fumy bamboo steamers.

I was thinking of ways for arts and culture workers to demonstrate solidarity. Part of what we can do is contribute to support systems for our communities, or at least start a conversation about coping with racialized aggressions in this time of crisis. I reached out to arts and culture workers and groups in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa who work in and with Asian Canadian communities to conceive, collect and share strategies to support businesses (especially those in Chinatowns), senior members who may be more isolated, and each other.

I asked:

How would you suggest supporting, or how have you been supporting, your community in this difficult time? And what have you been doing to cope with social distancing protocols and prevailing (micro)aggressions?

Doris Chow (co-founder of Youth Collaborative for Chinatown, Vancouver):

I continue to work on the front lines in the Downtown Eastside and live in the Chinatown/Strathcona neighbourhood, so I have the advantage of witnessing the changes in the neighbourhood on a daily basis while most are isolating at home. Several weeks ago, I came across graffiti on a prominent wall on Keefer Street, saying “BATSOUP.” About a week later, someone had crossed it out, and then it appeared in a second location. This is in addition to myself and my Asian colleague experiencing racism from people on the street and hearing accounts of a business owner getting prank called. I have yet to find out from other businesses if they have been experiencing the same.

The City of Vancouver and Vancouver’s Chinatown BIA have painted over lots of the graffiti in the neighbourhood, but for some reason, as of April 12, the racist graffiti on Keefer remains. I also just saw that there was racist graffiti at the Chinese Cultural Centre, which has since been removed and fenced off.

My colleague and I organized a #IWillEatWithYou event on March 13. Many joined us for dinner at Floata Seafood Restaurant to support a business that had been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. A number of people also donated funds toward meals for low-income seniors. Because of how quickly things changed in the days following the event, we weren’t able to figure out what to do with the funds until recently, as we wanted to understand what seniors actually need. To date, a portion of the funds has gone to purchase meal vouchers from Kent’s Kitchen, with the vouchers being distributed to the low-income residents of the May Wah Hotel. A small portion also went to immediate essentials such as prescription medications and phone bills. And we will continue to work with additional Chinatown businesses (such as produce shops) to purchase gift cards or vouchers for seniors in the community.

Yet Keen Seniors’ Day Centre Christmas gathering, Ottawa, 2019. Courtesy Alvis Choi.

Yet Keen Seniors’ Day Centre Christmas gathering, Ottawa, 2019. Courtesy Alvis Choi.

June Chow (co-founder of Youth Collaborative for Chinatown; sister of Doris Chow):

For us, being able to show care for seniors through Chinese (Cantonese) language has been the most pressing work, to ensure that they receive accurate information and that their mental and emotional health remains strong under self-isolation. We know that among seniors, a strong spirit is just as important (if not more so) as physical health in fighting the virus. Technically our grandmother died of pneumonia, but really, she gave up on living after being placed in a care home and losing her independence and sense of purpose.

With that said, there have been a number of Chinese-language phone banks popping up where volunteers check up on seniors to ask about their mental health and day-to-day needs. I’m a director of my Chinese society (Hoy Ping Benevolent Association of Canada), based in Chinatown, and our board has organized a telephone campaign to check in on our 2,000-plus members and their families, many of whom are elderly and at home feeling afraid.

Youth Collaborative for Chinatown teaches a Cantonese Saturday School program in Chinatown for adult learners, and we had to cancel the term halfway through, in mid-March. Our final class before calling it quits included learning the following phrases related to COVID-19, for students to use in conversations with their parents/elders to show care and concern, and to provide some comfort. At this time, they serve as the equivalent of “Have you eaten yet?” used under normal circumstances to show care for one another.

***

有冇洗手呀?

yáuh móuh sái sáu a?

Have (you) washed (your) hands?

sái jó / meih sái

Yes I have / No I haven’t

* * *

有冇消毒呀?

yáuh móuh sīu duhk a?

Have you disinfected?

sīu duhk jó / meih sīu duhk

Yes I have / No I haven’t

* * *

自我隔離

jih ngóh gaak lèih

Self-quarantine

留喺屋企

làuh hái ūk kéi

Stay at home

* * *

保重身體

bóu juhng sān tái

Take care (of your body/health)

Alvis Choi (artist and community worker, Ottawa):

I work with Chinese seniors in a drop-in day centre in Ottawa, which has been closed since mid-March. We’ve been doing phone outreach to 180-plus seniors and while many are doing fine with their own resilience and the support of their children, there are some who need more support. Chinese seniors who live alone or with only their spouses do not have access to many services offered by the city or community, because of language barriers and a lack of access to or literacy of technology. This population is at higher risk and some were still going to the stores because they needed to. Our day centre, when open, offers daily movement and cultural classes as well as social opportunities. Many seniors are now coping by keeping busy: cooking, cleaning, staying active, taking walks, etc.

We are supporting Chinese seniors by helping the most isolated get groceries and providing phone check-ins and emotional support. We are also offering virtual programming (such as Tai Chi and line dancing on Zoom!) and the technical support that it requires for seniors to participate. But with only part-time staff, our capacity is limited.

If you can, consider donating to us, Yet Keen Seniors’ Day Centre via CanadaHelps: https://www.canadahelps.org/en/dn/12742. (It is very important to select “3. Yet Keen Seniors’ Day Centre” to indicate where you would like the funds to go.) You will get a tax receipt for donations of more than $20, and any donation helps the operations of the centre tremendously. We receive municipal and provincial funding but also rely on community donations to keep running.

Alvis Choi’s art for their two-year-old friend, a painting inspired by the toddler’s quote, “Do you prefer this side?,” and paper owl with movable wings.

Alvis Choi’s art for their two-year-old friend, a painting inspired by the toddler’s quote, “Do you prefer this side?,” and paper owl with movable wings.

Artist Mary Sui Yee Wong has been making cloth masks and generously donated a batch to our seniors’ centre. Ottawa is unlike Toronto or Vancouver, where there are a lot more resources for the Chinese senior community. Yet Keen is one of the few places in Ottawa that serves this population, and it’s important that it stays financially healthy during this time. Of course, many artists are also struggling at this time, so do take care of yourself first!

For myself, keeping up with three meals a day and a moderate amount of exercise has been working. The situation is bringing up anxiety and past trauma that I do not feel excited about dealing with. I’m allowing myself to do the bare minimum to stay healthy and mentally well. Cooking has been a great way to feel productive and is nourishing at the same time. When I have more energy, I try to draw for my two-year-old friend. I refuse to take on new projects at this time—I just need to rest and do what feels best in the moment, without any commitment.

Mary Sui Yee Wong (artist and activist, Montreal):

Whether it’s because of the silence in my studio since the garment factory next door closed, leaving workers without a job, or the fear that my brother in Vancouver, who contracted the virus, might pass it onto his family, or feeling glad that my parents didn’t live to face this hardship, or worrying about how Chinese seniors too scared to leave their homes are coping, or the anger I feel around the rise of anti-Chinese sentiment—whatever the case, the activist/artist in me just can’t help but feel a sense of urgency to do something.

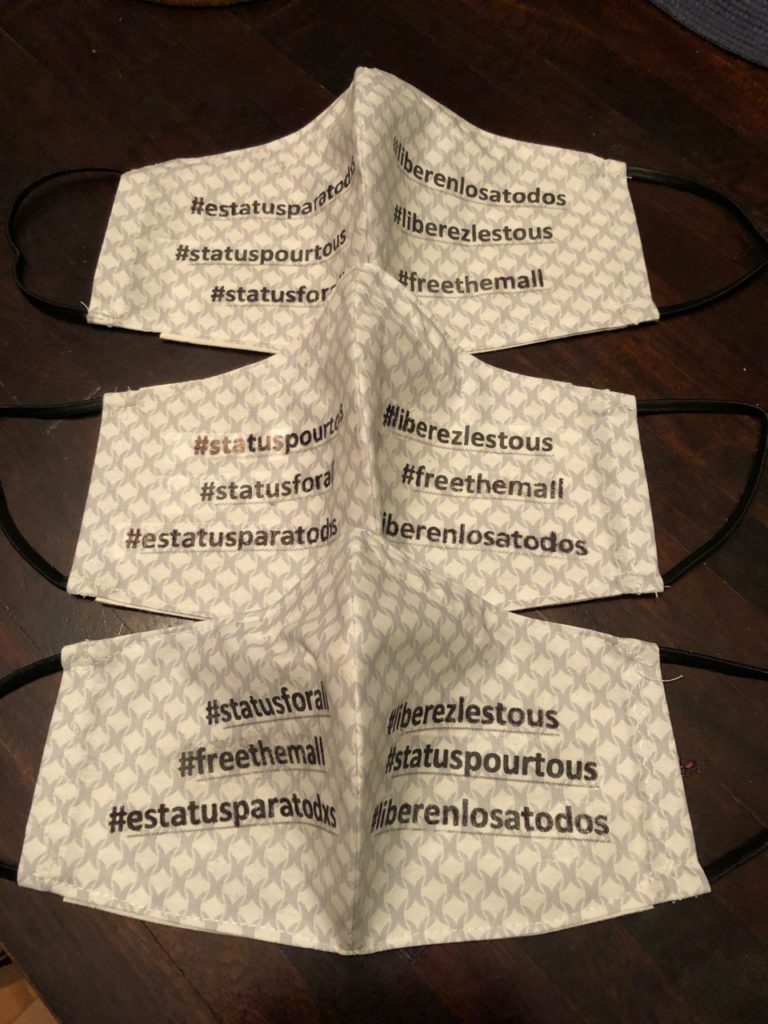

That’s how my sewing project began. After finding out that Alvis Choi was struggling to find funding for Yet Keen Seniors’ Day Centre while transitioning to support their seniors at home, the idea to gift this community with custom masks excited me.

Sewing a few dozen masks for Chinese seniors was easy enough. It was even easier to turn it into an art project and rally the Facebook community to support my fundraising campaign for Yet Keen. I’m looking into how this can be a source of funding for the Montreal-based community as well, once I can source more materials.

Mary Sui Yee Wong’s studio, April 4, 2020. Photo: Mary Sui Yee Wong.

Mary Sui Yee Wong’s studio, April 4, 2020. Photo: Mary Sui Yee Wong.

Sample of masks donated to Solidarity Across Borders, April 27, 2020. Photo: Mary Sui Yee Wong.

Sample of masks donated to Solidarity Across Borders, April 27, 2020. Photo: Mary Sui Yee Wong.

Maybe this effort didn’t come from nowhere. Maybe it has something to do with the conversations I’m having with students during my online Methods and Materials group study course that I’m teaching for Goddard College. It explores ways to reconfigure and decolonize craft. We’ve been talking about what it means to be an artist during the crisis, and thinking out loud about artmaking, use value and social engagement. Whatever the reason or impetus, it feels important to use my hand, my labour and my time. Making art in a time of social distancing and self-isolation without access to materials or commercial resources feels like an act of resistance that builds resilience.

I don’t have any advice for how other artists might make use of their craft to offset the quagmire we are in, but we need to open our eyes and see that this pandemic is racist: it is white privilege and it is divisive. Whatever artists of colour can do to shift the focus, shed light on such disparities and bring a bit of relief to the underserved feels key.

What COVID-19 has revealed is that in times of desperation and scarcity, the nation-state requires scapegoats…

I don’t want to “return to normal,” because normal wasn’t working.

David Ng (artist and curator, Vancouver):

The surge of anti-Asian racism reveals the fallacies of the “model minority” myth—that as Asians, we can achieve racial equity if we work hard enough, don’t complain and don’t rely on social security. These forms of recognition, where our cultural identities are sanctioned only under particular conditions, are contingent on the stability of the white supremacist nation-state. What COVID-19 has revealed is that in times of desperation and scarcity, the nation-state requires scapegoats. We’re seeing this unfold in xenophobic violence, and I’m interested in how we can use arts to transform our (queer, Asian) futures. I don’t want to “return to normal,” because normal wasn’t working. The “model minority” pressures do not provide space for Asian people to flourish, and art has the potential to imagine a journey away from the recognition politics of “diversity and inclusion.” What values need to shift? How can relationships be recalibrated for this future?

Self-isolation has been particularly hard because of this pressure to produce and continue to work “as normal” under the pandemic circumstances. It leaves little room to process the collective and individual trauma that we are going through. I believe this has other implications for Asian folks, who are discursively being faulted for “causing” the pandemic. To add to this, Chinese cultural rituals that are usually practised socially are now not possible or have to take new forms. Finding new ways of holding the community together has been a way for me to carry on—and I believe that art and continuing cultural practices, particularly as an Asian person, has been a way for me to care for myself.

Laiwan (artist and writer, Vancouver):

While I don’t live in Chinatown, I’ve lived on the east side of Vancouver since my arrival here as an immigrant leaving the war in apartheid Rhodesia in 1977. My allegiance and love for Chinatown are deep as I am driven by recognition of its Toisanese (Taishanese) roots.

In my creative practice and in teaching, I tend to take the long view. How can we shift larger, dominant hegemonic systems we have inherited that do not work and are no longer valuable for our survival? The “yellow peril” narratives are very old, and the violence, and I would say rape of ancient China by imperialism, especially with the devastating Opium Wars in the 1800s to crack open China’s wealth while causing the collapse of Chinese social structures, is deep within the memories and bodies of the people.

How we became migrants, and how the Toisanese in particular inadvertently started Chinatowns around the world, was not out of some “business entrepreneurship” or mobility of global travel, but out of survival after being forced out of their homes because of enforced cultural and social collapse and then being forced to live in a ghetto within the white supremacy of the West.

Two views of the site of Laiwan’s Fountain: the source or origin of anything (photographic mural), 2014. At the same location at Keefer and Columbia Streets, Vancouver, photos show the Georgia Viaduct and False Creek waters in 1961 (photographer unknown) and 2011 (photo: Keith Freeman).

Two views of the site of Laiwan’s Fountain: the source or origin of anything (photographic mural), 2014. At the same location at Keefer and Columbia Streets, Vancouver, photos show the Georgia Viaduct and False Creek waters in 1961 (photographer unknown) and 2011 (photo: Keith Freeman).

So the long view, in my mind, is one that has a critical reading on imperialism and colonial empire-building when looking at anti-Asian racism. With incredible violence enacted on many different communities globally, including the Indigenous peoples here in Canada, and the Indigenous Zimbabweans when I was growing up in apartheid Rhodesia, divisions via racism and discrimination benefit capitalist, neocolonial and now neoliberal forces.

How Chinatown, a once busy and thriving centre of culture and business, became deliberately impoverished along with the Downtown Eastside…one can look at governing decisions to host Expo 86 and the desire to present Vancouver as an international city of luxury and wealth. This gentrified Vancouver, further ghettoizing all the unwanted into the DTES—poor people, sex workers, those whose lives were devastated by addiction and people of colour—all foisted together around Chinatown, Hogan’s Alley and Japantown, effectively to hide these elements from the newly birthed version of the city post-Expo 86.

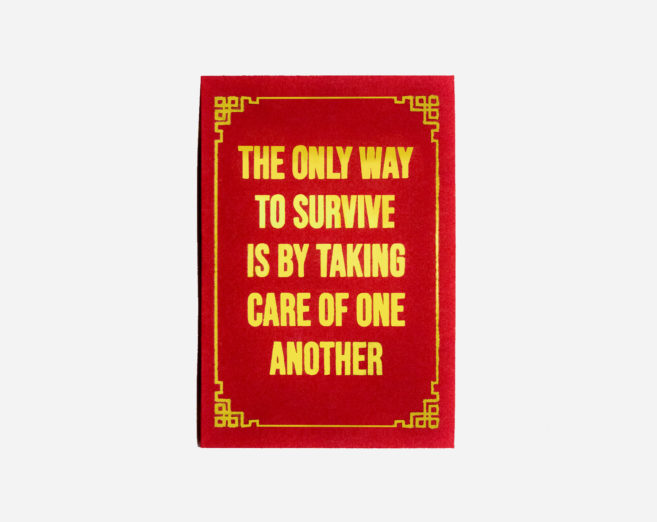

What gives me hope in these times is a return to the relational processes that originally helped us survive… in allegiance with the many other cultural groups similarly ghettoized

In our work with the Chinatown Legacy Stewardship Group, our task is to recognize how Chinatown flourished—it was not through mainstream acceptance of the Chinese into Western society and its systems of business, but through sheer tenacity, resilience and innovating in ways that could bypass or go unnoticed in a society that held incredible discrimination, via laws and policies, against not only Asians, but Indigenous and Black communities as well.

What gives me hope in these times is a return to the relational processes that originally helped us survive, which are in allegiance with the many other cultural groups similarly ghettoized—most importantly First Nations, whose unceded lands have been stolen and parcelled out, displacing generations from their ancestral homes and life-giving land resources. This is a global story. This understanding provides us some insight into what alternatives we must invest in: strengthening of the commons, providing shelter and food for those without and innovating businesses and collective activities that are site-specific and situational so that they speak to these new conditions.

Luq’luq’i : a herbal lounge with T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss and Anne Riley, sharing Indigenous medicines and stories of lands and waters at Laiwan’s Mobile Barnacle City site-specific installation, 2018.

Luq’luq’i : a herbal lounge with T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss and Anne Riley, sharing Indigenous medicines and stories of lands and waters at Laiwan’s Mobile Barnacle City site-specific installation, 2018.

To understand class struggle, and in relation to anti-racism solidarity work, Chinatown needs a new definition of “business as usual.” It needed this before the pandemic, and now we need to accelerate identifying the relational processes among our communities. We see neighbourhood networks strongly surfacing to help each other, and it is proven that to survive such great uncertainty, helping others is the best solution to maintaining one’s own well-being. Of course, it’s okay to ask for help, and to return such help one day.

That is how the original Chinatowns worked, and how they built vibrant and active neighbourhoods. We see how realty gentrification strategizes to take all of that. Historically, in Chinatowns across North America, along with Black neighbourhoods as well as Indigenous territories, we see this battle against erasure.

The greed of Western imperialism and capitalism has never disappeared. This is not a new “yellow peril,” but an extension. Specific details may be different, and we may have mistakenly thought we were free of it, that we had proven ourselves to be worthy of being included in the dominant status quo, but racism and white supremacy have increasingly shown themselves in the last five to ten years.

This is how I cope as an artist and as a descendant of a long line of Toisanese: in learning to care for our elders, in building this home together, in remembering stories from even beyond my generation and in retrieving bodily and cellular memories through things like Tai Chi, Qi Gong, Taoist philosophy and meditation. Again, it is the long view. I feel my ancestors with me, and this can be joyful with gratitude. And while I cannot do much outside our house, as my mum is vulnerable to infection, I do not feel alone. It was the Ching Ming festival recently, and my mum and I will go visit the cemetery.

This series continues with part two.

Laiwan’s Mobile Barnacle City, 2018, installed in Vancouver at 105 Keefer Street, the site of a contested development proposal, and where the waters of False Creek once flowed at the intersection.

Laiwan’s Mobile Barnacle City, 2018, installed in Vancouver at 105 Keefer Street, the site of a contested development proposal, and where the waters of False Creek once flowed at the intersection.