Montreal has long been fertile territory for independent, experimental art and DIY projects. Cheap rents, the unique ecosystem of Francophone culture, the influx of young Anglophones from the rest of Canada seeking an expat experience within their own country and the camaraderie and seclusion bought on by long, cold winters are just a few of the factors that add up to a city that both generates and welcomes artists who thrive on doing their own thing.

The French word for “artist-run centre”—centre d’artistes autogéré—contains a connotation of political independence that’s absent from the more prosaic English phrase: autogestion means “self-determination.” Quebec has more of these self-determined art centers than anywhere else in Canada: in Montreal alone, there are 24 such venues registered with the Regroupement des centres d’artistes autogérés du Québec (RCAAQ)—and those are only the officially recognized ones (Toronto, by comparison, has roughly half as many ARCs, despite its larger population).

Montreal also has long history of apartment or studio-based galleries and other off-the-map projects that are neither commercial galleries nor traditional ARCs: David Armstrong Six and Iliana Antonova’s Silver Flag, Danielle Saint-Amour and Willy Brisco’s WW2, and Philippe Hamelin and Sophie Bélair Clément’s La Mirage are some of the notable venues to have come and gone in recent memory. As in other cities, such projects are often—though not always—initiated by artists and curators recently out of art school as platforms for emerging talent and experimental exhibitions. These kinds of ephemeral arrangements allow for a continuation of the kinds of conversations and connections that happen at school without subjecting their participants to the pressures or constraints of a full-scale commercial gallery or institutional non-profit.

What’s unique about the latest generation of DIY spaces, though, is the degree to which they’re networking internationally, a factor enabled by the current ease of circulating documentation of exhibitions through art blogs and social media. Increasingly, this kind of screen-facing DIY space for emerging artists is becoming an essential part of the art-world landscape, connecting artists in Montreal with others in Toronto, Berlin, New York, Los Angeles and beyond—even as mid-level galleries are struggling to survive in a market crowded by art fairs and lorded over by blue-chip gallery empires. In Toronto, for example, the recent closures of Jessica Bradley Gallery and Diaz Contemporary have left a void that’s been partly compensated by a new crop of upstart spaces.

In Montreal, the first phase of this recent wave has already come and gone. Pop-up venues like Galerie Éphémère (which was run out of a shipping container on the edge of the St. Lawrence), Wanusay and French Restaurant were never meant to last, but CK2 (founded by Stephanie Creaghan and Jessica Kirsh) was more ambitious: it hosted six exhibitions at its Mile-Ex space between November 2014 and October 2015, and has since morphed into a mobile curatorial project following Kirsh’s departure for New York.

Since CK2 left their physical space in late 2015, the DIY art scene in Montreal has reached a critical mass. A network of young, mutually supportive spaces have opened in studios, apartments, storefronts, in the bustling Belgo Building, and, in one case, a condemned auto-repair shop.

Installation view of “The Garden,” featuring paintings by Claire Milbrath and Darby Milbrath with ceramics by Étienne Chartrand and Trevor Baird, at Project Pangée, June 11 to July 30, 2016.

Installation view of “The Garden,” featuring paintings by Claire Milbrath and Darby Milbrath with ceramics by Étienne Chartrand and Trevor Baird, at Project Pangée, June 11 to July 30, 2016.

Projet Pangée

Projet Pangée, operated by Julie Côté (who holds an MA in Library and Information Sciences from McGill University) and Joani Tremblay (a recent Concordia MFA grad), occupies a space in Montreal’s downtown Belgo Building, a former department store and garment industry workshop that now houses numerous art galleries and studios. When the previous host, Galerie Pangée (where Côté worked under then-director Margot Ross), closed its doors in 2012, it became office and storage space for the art consulting and secondary-market dealings of founder Pierre-Laurent Boullais. In 2015, Côte asked Boullais if she could take over the gallery, and re-launched it as Projet Pangée that November. In January 2016, Tremblay curated the gallery’s second show, “Drawing is the New Painting,” and subsequently came on board as co-director.

Côté and Tremblay describe their arrangement with Boullais as a “golden opportunity”: they have carte blanche, and he fully finances the project without pushing them to operate as a conventional commercial gallery. They do not represent artists, though they’re working on building relationships with collectors and they maintain a presence on Artsy. They are also looking forward to exhibiting at the next Material Art Fair in Mexico City in February of 2017.

Curatorially, their focus is on local and international emerging artists and they emphasize youth, colour and playfulness, an attitude that also manifests in their effusive approach to installation: their space is often filled to profusion with works hung salon-style, displayed on zigzagging labyrinths of folding walls, or sprawling across the floor.

Looking to the LA art scene (they cite Night Gallery as a particular influence) and young Lower East Side New York galleries, they explain that they are “interested in exhibiting what we believe to be missing or absent from the Montreal art scene. We find galleries and artist-run centres being often too serious or having common, specific tastes which tend to value minimalist or conceptual displays.” Their ethos is also reflected in the sexy, edgy content of Montreal’s The Editorial magazine, whose editor, Claire Milbrath, was included in a show titled “The Garden” at Projet Pangée this summer.

Projet Pangée’s debut a year ago coincided almost exactly with the closure of CK2’s physical space, so it’s appropriate that Pangée’s current exhibit, “The Digital Cliff,” was curated by CK2’s Stephanie Creaghan and Jessica Kirsh—their first project back in Montreal since going mobile. In Spring 2017, Projet Pangée will also be casting its eye westward with a retrospective of Vancouver artist hub Sunset Terrace, guest curated by Graham Landin.

Installation view of a group exhibition featuring works by Elizabeth Newman, Richard Frater, Pat Foster and Jen Berean, Jesse Chapman and Ashley Carter at Raising Cattle, April/May, 2016.

Installation view of a group exhibition featuring works by Elizabeth Newman, Richard Frater, Pat Foster and Jen Berean, Jesse Chapman and Ashley Carter at Raising Cattle, April/May, 2016.

Raising Cattle

Raising Cattle is a studio gallery in the Bovril building at the corner of Avenue du Parc and Van Horne, founded by Jackson Slattery and Adam Revington in April 2016. Both non-natives of Quebec, they found it strange that, despite the proximity to the US, there seemed to be little dialogue between French-Canadian and American artists and art spaces. “Our starting point,” Slattery explains, “was to bring artists outside of Canada to exhibit alongside Quebec artists.”

Following their second exhibition, Revington moved home to London, Ontario, where he founded another space, Carl Louie, with Zoe Mpeletzikas, and Adam Sajkowski joined Slattery at Raising Cattle. Originally, the two were using the space as their studio when they didn’t have a show up, but they’ve since acquired a second space for their own work.

In terms of programming, Raising Cattle has no strict mandate, aside from their commitment to mixing local and international artists at the emerging level—their last show featured New York–based Australian artist Christopher Hanrahan and Montrealer Nicolas Lachance, and past shows have included New Yorkers Dana Hoey and Em Rooney, New York–based British Columbian Aaron Aujla, Massachusetts-based Norwegian Lina Viste Grønli and Torontonian Jenine Marsh, among others. Aesthetically, Slattery and Sajkowski seem to favour understated, enigmatic, object-based work reminiscent of ’90s scatter or slacker art.

On the business end, Slattery has “no interest in Raising Cattle becoming a commercial venture.” He is also easygoing about the ephemerality of many small-scale art spaces: “It seems that cities with healthy art scenes are constantly turning over new spaces…. There is always a need for alternatives to the more established artist-run spaces that are often sluggish and weighed down by bureaucracy and concerns over funding.”

Though currently closed for the winter season, Raising Cattle is looking forward to its second year of exhibitions in 2017. A group show featuring Kate Newby, Mark Hilton and Tove Storch is planned for March.

Installation view of paintings by Magalie Guérin at Soon.tw, October 12 to November 12, 2016.

Installation view of paintings by Magalie Guérin at Soon.tw, October 12 to November 12, 2016.

Soon.tw

Soon.tw was originally conceived by Jérôme Nadeau (who finished his MFA at Concordia this year and appeared alongside Joani Tremblay at Parisian Laundry’s annual “Collision” exhibition of graduating students) as a series of publications showcasing the raw material or side projects that feed artists’ primary work while remaining invisible to most audiences. The first edition, a book by Jean-Philippe Harvey, came out in 2014 and the name of the series is a kind of in-joke about when the next one was forthcoming (“Soon, soon…”).

Nadeau was also the co-curator of Galerie Éphémère over the summer of 2015. When a room opened up next to the railway-adjacent painting studio that Jean-François Lauda has occupied for 13 years on Bellechasse, he gave Nadeau a call and they immediately went to work setting up Soon.tw as a physical gallery. Their first show, by Montreal-born, Chicago-based painter Magalie Guerin, opened this October, following ambitious renovations and unexpected red tape. Guerin’s Chicago gallery, from whom they borrowed the works, was sending them to Art Basel immediately after, and the shipping and insurance requirements considerably exceeded what a typical DIY gallery faces for their first exhibition. It was a high bar to clear (though a useful learning experience) for an operation that isn’t focused on sales and won’t represent artists.

Soon.tw’s main aim is “creating connections between works and artists, to curators and collectors that might push it forward.” Nadeau and Lauda are interested in showing artists that, like Guerin, are connected to Montreal but not known or shown here. They’re leery of falling into the comfort zone of just showing friends and intend to pursue older and under-appreciated artists—Lauda even expresses a predilection for folk art—though their second, current exhibition is Jackson Slattery, a friend who also co-runs Raising Cattle.

Nadeau and Lauda also note that they’re, “trying to avoid that Art Viewer aesthetic, which all started with Tomorrow,” citing their frequent physical disappointment with work in a space and their own interest, as artists, in materiality. The publication series is alive and well, too: the recently-released second and third editions are by Lauda and Jeanie Riddle, a Montreal-based painter and former director of Parisian Laundry gallery.

Installation view of “Hybrid Objects,” featuring works by Hanna Hur, Chris Dorland, Corin Sworn, Alex Morrison, Zin Taylor and Adrianne Rubenstein, at L’inconnue, October 21 to December 17, 2016.

Installation view of “Hybrid Objects,” featuring works by Hanna Hur, Chris Dorland, Corin Sworn, Alex Morrison, Zin Taylor and Adrianne Rubenstein, at L’inconnue, October 21 to December 17, 2016.

L’inconnue

L’inconnue is unique among other new Montreal art spaces in that it is a fully functioning commercial gallery. Situated amid rapid development in St-Henri, it’s the first contemporary art gallery in the neighbourhood, a short trip west of the more established venues (Arsenal, Division, Antoine Ertaskiran, Parisian Laundry) around Griffintown. As proprietor Leila Greiche puts it, “I’m standing on my own here.”

Though born in Montreal, Greiche has spent a number of years abroad, first as a student at Sarah Lawrence College, just outside of New York City, and in the art business program at Sotheby’s Institute of Art. She put that education to use as an intern in the Museum of Modern Art’s conservation department, at Christie’s auction house and in the studio of the late artist Dennis Oppenheim. Following that, she took jobs at Carroll/Fletcher gallery and Phillips auction house. Then, after a brief stint in LA, Greiche returned to Montreal and decided to settle down: “It was time for me to root and develop my reputation.”

Though she had initially only conceived it as a one-off exhibition, once she had started assembling L’inconnue’s debut, she began to feel confident enough to set up permanently. “Hybrid Objects,” the inaugural group show which opened in October and continues to December 17, gathers an impressive selection of emerging and well-known Canadian artists: Chris Dorland, Hanna Hur, Alex Morrison, Adrianne Rubenstein, Corin Sworn and Zin Taylor. Greiche is keen to highlight artists who are “not the Canadian artists we always see—definitely not in Montreal,” and it’s worth noting that no one included in “Hybrid Objects” is currently living in Canada.

Though Greiche has ambitions to cultivate an international clientele and hopes to see Montreal become a more prominent stop on the international art circuit—which is one of the reasons she intends to keep her shows up for longer than usual, three months at a time, in order to catch as many visitors as possible—she is also starting slow. She has no plans to represent artists or to participate in art fairs, as yet. “Working with an art fair,” she says, “you take on their identity. I’m still trying to build my own. I want to be strategic, not impulsive.”

L’inconnue’s next show will be New York–based Vancouver painter Brian Kokoska (one of this year’s RBC Canadian Painting Competition nominees), opening in January.

Entranceway view of a group exhibition featuring works by Alan Belcher, Simon Belleau, Julian Garcia, Kelly Jazvac, Puppies Puppies, UV Production House and Andrew Norman Wilson at Vie d’Ange, October 7 to November 7, 2016.

Entranceway view of a group exhibition featuring works by Alan Belcher, Simon Belleau, Julian Garcia, Kelly Jazvac, Puppies Puppies, UV Production House and Andrew Norman Wilson at Vie d’Ange, October 7 to November 7, 2016.

Vie d’Ange

In the late summer of 2015, a group of collaborators converted a disused auto garage in Montreal’s Mile-Ex neighbourhood (conveniently located across a parking lot from popular bar Alexandraplatz) into a space for exhibitions and events that was dubbed 820 Plaza. One of the projects staged there was “Unsafe at any Speed,” a group exhibition curated by Eli Kerr that brought a Ford Explorer into the space as both a thematic prompt and physical display unit for art works. Kerr’s concept was to treat the SUV as a contemporary relic, a symbol that condensed the decline of the American auto industry, the war-on-terror era’s obsession with “security” (as emblematized by big, powerful cars), and the implications of fossil-fuel dependency and ecological crisis.

A year later, Kerr and Daphné Boxer have renovated part of the 820 Plaza space and relaunched it as Vie d’Ange, a polyvalent phrase that conflates the literal “life of an angel” with a Quebecois colloquialism for street refuse and a French idiom for the process of draining a container of liquids (in France, an oil change is a “vidange huile.”) Their inaugural group show extended the ambitious concept of Kerr’s earlier project, with a number of works obliquely related to the toxic consequences of oil drilling and a broader inquiry into the mutual entanglement of human and non-human forms of organic material.

The contribution of pseudonymous artist Puppies Puppies (who recently appeared in this summer’s Berlin Biennale) was a pig’s heart pierced by an archery arrow, and Chicago-based Quebecois artist Simon Belleau’s sculpture incorporated a turtle shell into a Roomba vacuum. Other participating artists included LA-based Andrew Norman Wilson (whose visceral video work was the highlight of the show), UV Production House (aka Brad Troemel and Joshua Citarella) from New York, Montreal-based Julian Garcia and Toronto-based Alan Belcher, whose inclusion testified not only to rising awareness of the artist’s work, but to resurgent interest in his activities in the 1980s as co-curator of Gallery Nature Morte in New York’s Lower East Side.

Kerr and Boxer are aware of the constraints of their space. As an un-insulated building, it will be difficult to maintain through the winter and, moreover, it is slated for eventual demolition, so their time is limited (though indefinite). For now, they’ve just opened their second show, a duo exhibition of Montreal painters Jean-François Lauda and Brendan Flanagan, and they hope to continue staging innovative projects as long as circumstances allow.

Installation view of Julian Hou’s “Help Me Remember” at L’escalier, December 12, 2015 to February 14, 2016.

Installation view of Julian Hou’s “Help Me Remember” at L’escalier, December 12, 2015 to February 14, 2016.

L’escalier

L’escalier originated in 2012 with the idea of founding a collaborative magazine, financed as a series of editions. Conceived by curator and writer Vincent Bonin and artists Lorna Bauer and Jon Knowles, the idea was, in their words, “to thematize the tenuous relationship between intellectual labor (eg: criticism and publicity) and other mechanisms that accrue value in the art field (eg: collecting and speculation).” Two such editions were produced: the first in collaboration with Vienna-based artist Yuki Higashino for Art Metropole in 2012, and the second with New York-based artist David Court at Montreal’s Centre des arts actuels SKOL in 2013.

While the magazine idea remains on the backburner, L’escalier hosted a screening of Vancouver artist Arvo Leo’s film Fish Plane Heart Clock in 2015 at the defunct La Mirage space. Around that time, Bonin, Bauer and Knowles began discussing the idea of opening an exhibition space of their own. In the fall of 2015, they refurbished a room of Bonin’s apartment as a small gallery and mounted their first exhibition, a group of fabric works and a sound piece by Vancouver-based Julian Hou.

L’escalier’s second show, staged this summer, was a Knowles Eddy Knowles (Jon Knowles, Michael Eddy and Robert Knowles) group exhibition entitled “Inhale/Exile,” an outcome of close to 10 years of research on the “cultural signification of smoking.” The next exhibition, slated for January 2017, will gather drawings by the Berlin-based painter Beth Letain.

While L’escalier is, like other recent DIY galleries, neither a commercial space nor an institutional one, its ethos is conditioned by Bonin’s extensive research into the history of artist-run culture in Canada, exemplified by the two “Documentary Protocols (1967–75)” exhibitions and accompanying publication that he produced between 2007 and 2008. Outside of Canada, Bonin, Bauer and Knowles are also looking to models such as 33 Orchard in New York, a cooperative venture that prioritized the advance of discourse and ideas over the market visibility generated by exhibitions.

In general, the three are keen to dispel received ideas that accrue around DIY art spaces and they emphasize mindfulness of the long history of such endeavors: “We think in most cases, the desire to have these spaces emerges from a feeling of urgency, of making things happen on the short term rather than to wait for institutional validation as well as to think directly about receivership and audience. This transcends the usual cliché that these spaces are always started by young artists due to institutional negligence, though that is obviously still a relevant concern. It’s an intergenerational phenomena as well, as people like Stephen Schofield and Michel Daignault have been operating their rue Rachel store front space for years, with very little visibility or outside praise. These domestic presentation spaces go all the way back to Refus Global.”

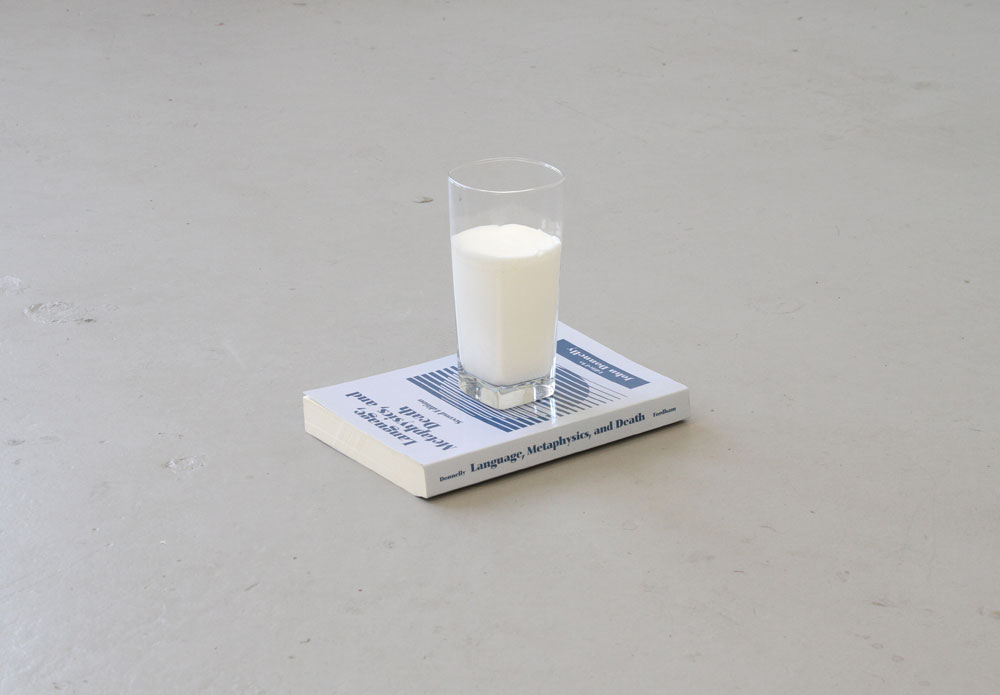

Lina Viste Grønli's Milk, Language, Metaphysics and Death, 2010, from a group exhibition at Raising Cattle, May/June 2016.

Lina Viste Grønli's Milk, Language, Metaphysics and Death, 2010, from a group exhibition at Raising Cattle, May/June 2016.