When you see my work you feel physical pain…and if you don’t…then there is something wrong with you. —Carrie Mae Weems, 1992

In an introductory art history course that I teach at a large public university in a mostly white, politically red state, I frequently assign, as part of a unit on iconoclasm and censorship, Sue Gibson Garvey’s 2002 essay, “Short Circuit: The Story of an Exhibition That Provoked Unforeseen Consequences,” (published in Between Ethics and Aesthetics, edited by Dorota Glowacka and Stephen Boos). This essay details events that occurred at the Dalhousie University Art Gallery in Halifax in the spring of 1992. As curator, Gibson Garvey brought in “No Laughing Matter,” an Independent Curators International exhibition featuring activist art addressing politics through humour. When gallery staff first saw the full selection of works, only a short time before the exhibition opened, they recognized the possibility that some of these works—specifically a selection of photo-text pieces from the series Ain’t Jokin’ (1987-88), by Carrie Mae Weems—might prove controversial in their unflinching engagement with the history of racist and anti-Black imagery and language in the United States. Removing these works from the exhibition was not considered; instead, the goal of gallery staff was to make the works accessible, to ensure that audiences understood their anti-racist intentions.

In her essay, Gibson Garvey describes the efforts made by gallery staff to develop “positive mediation” for Dalhousie students, and especially for African Nova Scotian students. One of these efforts was the invitation of University Employment Equity Officer Mayann Francis, and Black Student Advisor Beverly Johnson, to preview the exhibition in the hopes that their expertise and familiarity with the concerns of the Black student community would provide the gallery with guidance and support in their presentation of Weems’ racially-charged works. Following this preview, Francis and Johnson sent a letter to Mern O’Brien, Gallery Director, which provided gallery staff with their own preview of responses from many Black community members. It read in part:

“…we find the work of Carrie Weems to be offensive and degrading to black people. While we understand what Ms. Weems is attempting to do, we do not support this approach when attacking racism…The long term affect of these pictures on young minds regardless of colour can only be negative…One might argue that since Ms. Weems is a black artist, surely ‘it’ must be alright? Quite the contrary. Whatever motivates her to attack racism in this fashion is unclear…” (February 21, 1992)

Ultimately, the late recognition of possible problems with the work; the fact that the gallery employed no people of colour in management positions; and the failure to obtain hoped-for support from Black staff members at the university—such as Francis and Johnson—collectively made attempts at pre-emptive management difficult.

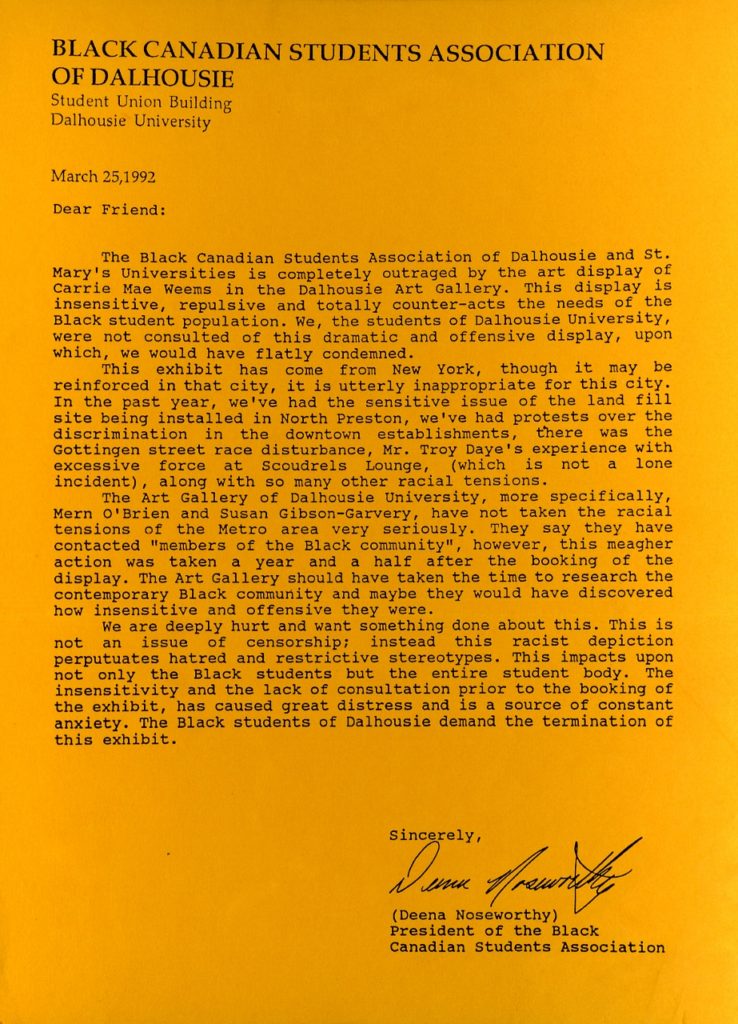

The events that unfolded after the exhibition opened presented gallery staff with what was described in Gibson Garvey’s text as “an excruciating moral dilemma.” First, Black Dalhousie students, followed by a growing mass of the broader public, reacted negatively to the works, many calling for them to be removed. In an ameliorative gesture, gallery staff posted a letter from Deena Noseworthy, the president of the Black Canadian Student’s Association of Dalhousie, on the wall near Weems’s works. The letter argued that the work “perpetuates hatred and restrictive stereotypes,” and called for its removal. The students were not appeased by this gesture. They staged a sit-in. Gallery staff encouraged them to sit on benches. The students wanted to stand in front of the works, blocking the view of other gallery-goers, and were angry that gallery staff would not permit them to do so. Security was increased. The works stayed up, despite mounting negative attention from local politicians, the media, and student and community groups. The president of Dalhousie maintained his commitment to freedom of expression, while actively distancing himself from both the gallery and Weems’s work in an editorial in the Dalhousie News.

The works in question pair black-and-white photographs with texts evoking racist jokes and stereotypes. Mirror, Mirror, one of the better-known works in the series, depicts a Black woman, her face in profile, holding a mirror. Instead of her reflection, what we see in the frame is a white woman, gazing out from behind the surface of the mirror. A text below reads, “LOOKING INTO THE MIRROR, THE BLACK WOMAN ASKED, “MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL, WHO’S THE FINEST OF THEM ALL?” THE MIRROR SAYS, “SNOW WHITE YOU BLACK BITCH, AND DON’T YOU FORGET IT!!!” This work provides a critique of racist beauty standards and their ideological inscription in classical children’s literature. Others, like Black Man Holding Watermelon, or Black Woman with Chicken combine a real individual with a stereotype-associated object; the personhood of the models in these photographs easily shatter the brittle stereotype indicated by their titles. In What’s a Cross Between an Ape and a Nigger? however, the brutality of concept and language just as easily degrades the humanity of the man depicted. This dehumanization is amplified by the contrast between the intimate framing of the gorilla, which gazes sagely over its shoulder at us, and the man, who is shot at a greater distance, in clinical profile, leaning, forward, mouth a bit open. The titular slur below him invites and entrenches any ugly stereotype of Black masculinity that viewers might be inclined to impose upon him. In this and other “riddle”-based works, the answer to the question is found adjacent to the work, covered by a red card that viewers may lift to reveal a punchline. In this case, it reads, “a mentally retarded gorilla.” This work was meant to hurt, as Weems herself said.

In our classroom discussions of these works and the controversy that erupted around them in Halifax, most of my students sympathize with the protesters, but prioritize free speech over cultural sensitivity, supporting the decision to leave the works on view. There are two points in Gibson Garvey’s essay to which students frequently return. First, they point out that Weems is an African American artist whose work is meant to challenge racism. Second, they cite the following passage from the assigned essay: “We…tried to engage the students in a conversation about the works themselves, but their leader said that they were too profoundly hurt by the exhibition to discuss it further, and they left.” Students easily grasp the logic of Gibson Garvey’s thoughtful account, and are effective in their arguments in the gallery’s favour. The fact that the artist is Black, and actively working against racism, means that the work is not—could not possibly be—racist. The fact that students refused to have a discussion with gallery staff, or with the artist, is evidence of willful ignorance of the work’s anti-racist intentions. There are two key assumptions implicit in Gibson Garvey’s text that are articulated, explicitly, by students. The first is that a protester’s concerns are invalidated by that protester’s refusal to engage in dialogue on the terms set by the institution they are protesting. The second is that the work has a positive outcome that outweighs any pain it may cause. Dig down, and beneath those two assumptions we find a third (rarely spoken aloud by my students, but not infrequently found in their written responses): the students who objected to Weems’s work just didn’t get it.

If the gallery staff was not racist, and the artist was not racist, how can the art be racist? In the worlds of both art and humour, the assumption is often made that the good intentions of the presenter mitigate the racist (or sexist, or transphobic) content of the art or the joke and the harm it causes. I mean, I get it, but as Francis and Johnson’s letter makes clear, getting a joke doesn’t make it fun to be the punchline. Every staff member working at a particular institution may be stridently antiracist, but still be working in the interests of white supremacy, if that is the underpinning of the institution and the system within which they operate. Those who have had little power to shape their own representation in the public sphere, who rarely see themselves represented at all, may reasonably balk when they finally see themselves represented—as a joke. Even if the joke is a joke about racism, rather than a racist joke, it may be frustrating to still be faced with the same old cruelties. To say that people should swallow their pain, because it’s “just a joke” or because it is that hallowed thing, Art, is disingenuous at best.

A quarter century after a group of Black students at Dalhousie University sought to use their bodies to block public view of a body of work that they saw as deeply harmful to themselves and to their community, Parker Bright, a Black artist in New York, stood before Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket, the words “BLACK DEATH SPECTACLE” on his back. At the 2017 Whitney Biennial, at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and elsewhere, communities that have suffered specific historical and racialized forms of violence objected to works of art that objectified that violence. Today, it seems absurd to ask if they “got it”—for who is better positioned to get it than those who have lived it? To claim otherwise is to admit to the open secret of the white supremacist foundations of the art world. This, I believe, is the unspoken heart of the unresolved conflict that emerged in Halifax in 1992; the students who protested Weems’s works were also protesting a system within which they had no representation, a system that made decisions about what pain they should or should not tolerate, and argued that it was for their own good. The mindset behind this system was articulated recently by writer Ijeoma Oluo, who published an open letter denouncing another writer’s use of her work. Oluo wrote, “…the idea that in 2018 we would still be ok with white writers talking about how they feel that black people should deal with their oppression is the most disturbing thing about this whole debacle.”

The author would like to thank Craig Ferguson for his generous assistance with access to archival materials.

This post is an expanded version of the article “Sensitive” in Canadian Art‘s Spring 2018 issue, which is themed on “Dirty Words.”