In Canada, pipelines, oil and gas, energy and labour all underscored the politics of the year. The Trudeau government announced in May that it was purchasing Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline and by late November, the Alberta government was cutting oil production, attempting to increase value in an ailing market. Meanwhile, General Motors abandoned production in one of its legacy cities to focus on electric self-driving cars. And the most recent report from the IPCC leaves us with just 12 years left to live—metaphorically-speaking. It felt like the urgency of depleted environments was in everything I read and saw this year, and the contradictory ways humans mediate and control the natural world became obvious to me like never before. Feelings mark the passing of time as much as any measurement does—we feel the seasons change as a calendar or clock marks time—but this year it felt like mostly measurement, with diminishing returns.

Early in the year, Postcommodity (Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist) presented a series of claustrophobic sound and video installations in an exhibition at the AGYU that reproduced the spatial anxieties of border zones. Land itself becomes a threat when embedded with sensors and surveillance cameras, and Postcommodity’s figuring of the American military as a monster in the desert articulated how violent forms of border control rely on continually mediated environments.

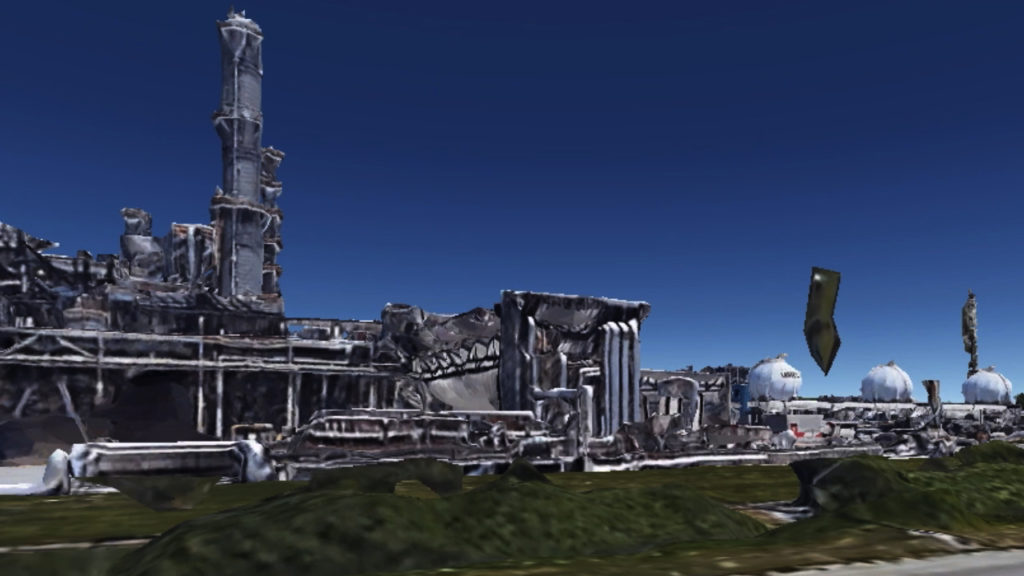

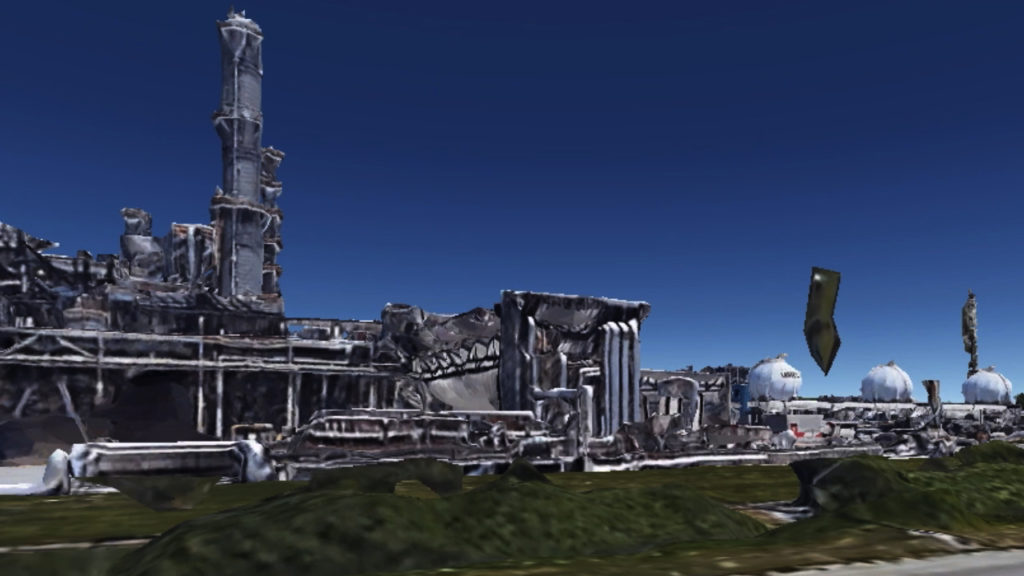

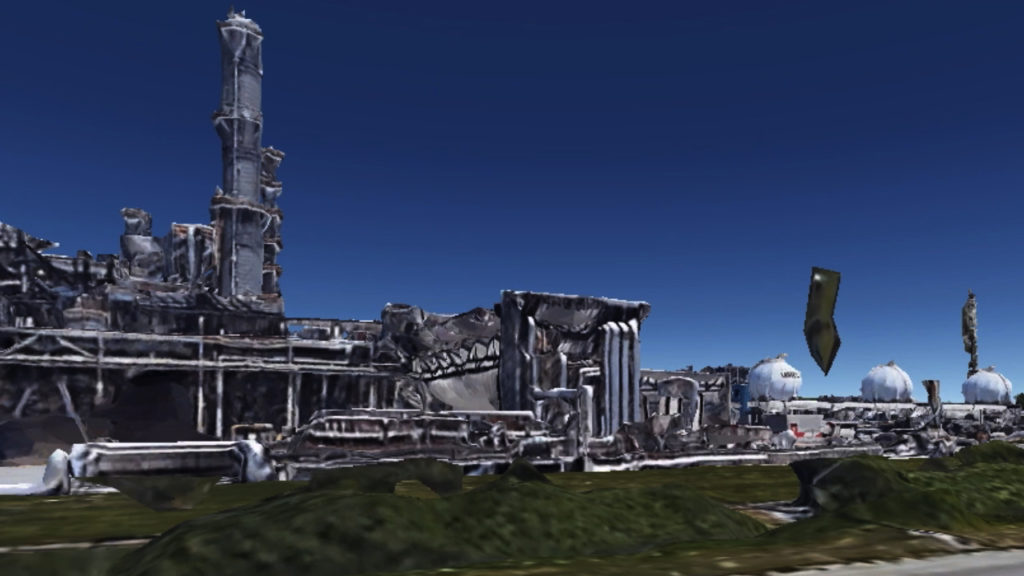

Christina Battle’s exhibitions, “Bad Stars” at Trinity Square Video and “Toolkit for Time Travel” with Serena Lee at YYZ Artists’ Outlet, used screens, CGI, Google Earth, GIFs, crowdsourcing and other digital technologies to speculate on the possibilities of unnatural futures. At TSV, the looming presence of Sarnia’s Chemical Valley was the focal point for multiple takes on pollution and disaster, whether from asteroid impact or the slow contamination of waterways due to chemical leaks and other heavy metals.

Christina Battle, BAD STARS (video still), 2018. Courtesy the artist.

Christina Battle, BAD STARS (video still), 2018. Courtesy the artist.

Christina Battle, BAD STARS (video still), 2018. Courtesy the artist.

Highly aestheticized images depicting environmental destruction in the “Anthropocene” are still up at the AGO, but of the AGO’s major exhibitions this year, it was Rebecca Belmore’s “Facing the Monumental” that offered the strongest statement on the harm humans are causing the earth, and each other. Belmore’s decades-long engagement with water and land rights, sovereignty and justice was evident; no other work so powerfully encapsulates the poetic contradictions of violence and survival, struggle and power, excess and scarcity than Fountain (2005), its twinned symbols of blood and water acting as metaphors for life, and its destruction. Elegantly curated by Wanda Nanibush, the exhibition was a highlight of the year.

Rebecca Belmore, Fountain, 2005. Single-channel video with sound projected onto falling water, 274 cm x 488 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Tower, 2018. Clay and shopping carts. Installed at the Art Gallery of Ontario. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Tower (detail), 2018. Clay and shopping carts. Installed at the Art Gallery of Ontario. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, tarpaulin, 2018. Installed at the Art Gallery of Ontario. © Rebecca Belmore.

In September, the Blackwood Gallery’s “The Work of Wind: Air, Land, Sea ” took an expansive approach to environmental crisis, unfolding site-specific installations, performances and events along Mississauga’s waterfront, forcing viewers to encounter the often inaccessible sites of industry (a Petro-Canada lubricants plant, an abandoned paint and resin factory, a CO2-production facility) that have contributed to climate change. Dylan Miner’s elegant, understated installations—seven platforms built from reclaimed timber and copper—required viewers to spend time at various sites, often only metres from security fencing, and with the knowledge that industrial pollutants are seeping into the earth, air and lake beside you. Surrounded by the warmth and smell of lumber and the healing properties of copper, it was an offering of rest—a rare experience to feel intimately connected to the enormity of industry.

At Oakville Galleries, David Hartt’s “in the forest” documents the overgrown site of Habitat Puerto Rico, Moshe Safdie’s long-abandoned housing complex designed for its proximity to nature. Now overtaken by the forest, the iconic concrete living spaces seem post-apocalyptic and monumental, and Hartt offers a subtle but precise critique of the failed environmental utopias of the ’60s. As Puerto Rico continues to rebuild from last year’s deadly Hurricane Maria and other climate-related disasters, the desire to separate built and natural environments seems futile.

David Hartt, Carolina I, 2017. Archival pigment print mounted to Dibond, 91.4 x 137cm. Commissioned by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Courtesy Corbett vs. Dempsey (Chicago).

David Hartt, Camuy II, 2017. Archival pigment print mounted to Dibond, 91.4 x 137cm. Commissioned by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Courtesy Corbett vs. Dempsey (Chicago).

David Hartt, Guayama, 2017. Archival pigment print mounted to Dibond, 91.4 x 137cm. Commissioned by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. Courtesy Corbett vs. Dempsey (Chicago).

Overlapping architectural and natural forms are likewise the concern of Abbas Akhavan’s “variations on a landscape,” a six-month-long site-specific commission at the Power Plant and one of the most original exhibitions to occupy its difficult clerestory space. Akhavan altered the windows above and used only natural, ambient light, allowing pink hues to flood the space through the summer months and then slowly dissipate as fall progressed. With the change of seasons, the pair of entangled, fighting white swans was replaced with precariously angled green-screen monitors, the fountain was emptied, a shrub-like form appeared bound tightly in plastic and the calming effect of running water was exchanged for the imperceptible hum of always-on devices. The too-bright monitors cast unnaturally fluorescent shadows and a working iPhone charger was helpfully added, so you can include your own screen in the mix. It’s an appropriately dark comment on how we encounter the earth’s elements—mostly through our devices. Nothing we think of as natural is now without human intervention, but, in demonstrating the darkness of our screen-based culture the work also teaches us new ways of looking for light, which is a poetic and welcome challenge in a year with little cause for environmental optimism.

Abbas Akhavan, variations on a landscape, 2018. Installation view, commissioned by The Power Plant, Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Abbas Akhavan, variations on a landscape, 2018. Installation view, commissioned by The Power Plant, Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Dylan Miner, Agamiing – Niwaabaandaan miinawaa Nimiwkendaan // At the Lake—I see and remember, 2018. Commissioned by Blackwood Gallery for The Work of Wind: Air, Land, Sea.

Dylan Miner, Agamiing – Niwaabaandaan miinawaa Nimiwkendaan // At the Lake—I see and remember, 2018. Commissioned by Blackwood Gallery for The Work of Wind: Air, Land, Sea.