In 1991, the fourth Havana Biennial focused on “The Challenge of Colonisation” and featured 150 artists from Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, Asia, and the Caribbean, and Indigenous artists and artists of colour from other regions. Among the participating artists was Rebecca Belmore, and her performance Creation or Death: We Will Win. In the piece, Belmore’s ankles and wrists are bound, as is her mouth. Falling to her knees and crawling, Belmore painstakingly carries a line of sand from a pile up a staircase towards the sky.

Watching the documentation of this piece nearly 20 years later, its resonance is still overwhelming to me. This is what colonialism in 2018 feels like. This relentless struggle of carrying forward that which is meaningful, despite being bound, despite monumental obstacles, is a struggle towards sky, towards freedom. The sharp focus on the artist, the fortitude of concentration, her relentless determination and her sound as she reaches the top, is affirmation. Yes, we will win.

We already have.

I’m in a Toronto breakfast place at College and Ossington visiting with Rebecca Belmore and Wanda Nanibush, the inaugural Curator of Indigenous Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Nanibush and Belmore are working together on Belmore’s upcoming show at the AGO, called “Facing the Monumental” and opening July 11. It is a large, retrospective exhibition spanning 30 years of Belmore’s work, including new pieces and old favourites. Nanibush has curated 20 major sculptures, installations, photographs and performance-based works, including Rising to the Occasion (1987–1989), Named and Unnamed (2002), and Fountain (2005), as well as a showcase of new works by the artist. Indeed, it is time to consider the worlds Belmore’s last three decades have gifted us.

“Facing the Monumental” is not their first collaboration—their relationship is deep and spans many years and many installations. I first met Rebecca in 2010, in Wanda’s living room in Peterborough. We were both part of Nanibush’s “Mapping Resistances,” a performance event commemorating the 20th anniversary of the so-called Oka Crisis. But today, Belmore takes me back to Cuba. She tells me Havana was the first time she left the continent. “Because I was speaking to an international third-world audience, I realized I didn’t have to speak [before the performance]. I could use my body to speak and speak without a language. That was really a turning point. I was bound with my hands and ankles moving towards the sky and freedom, which I think really changed, for me, the way I saw myself working in the future. That was a pivotal moment.”

I ask how.

“Just realizing that I can use my body to speak.”

I think I know exactly what she means and to confirm, I ask: “When you were speaking, you were explaining to white people. In Havana, you stopped centring whiteness.”

“Absolutely.”

I think about the impact of Belmore’s pivotal moment on my own life and practice with her refusal to centre whiteness in her own work, and how in that moment she changed her artistic practice, but also how I experience that practice. In her refusal, she gave me and my generation of artists, creators and intellectuals another option with regard to who we make work for. Without the standard white tour-guiding and cultural explanation, there is this inherent assumption that I am the audience. Me. Kwe. That she is making this performance for me. That I’m supposed to be there. That I have all the intelligence and experience I need to understand, interpret and find meaning in her work through my own everyday knowledge. This subtle shift comes with a gesture of trust. I let my guard down. I accept her invitation to come into her presence, her space, knowing that I won’t be hurt or ridiculed. She invites me into freedom, affirming my struggle, affirming our collective, beautiful, relentless struggle towards the sky. The brilliance here is that while I’m feeling that in my kwe bones, the work is speaking across audiences to Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples alike.

When Nanibush started at the AGO she had three artists—“my queens”—that she wanted to secure prominent solo shows for: Belmore, Shelley Niro and Faye HeavyShield. It is mind-blowing to me that this hadn’t already happened. But we all know why.

To make work informed by Anishinaabeg consciousness is a radical act particularly because Canadian society still makes the assumption that Indigenous peoples are without Indigenous thought, philosophies, theories and an intelligent engagement with the world around us based on profoundly different bodies of knowledge than western thought. We come from a different aesthetic and theoretical tradition, and because of this, Belmore’s practice speaks through and across audiences in a layered fashion. I’m drawn to Belmore’s work because she engages my Anishinaabeg knowledge and challenges me to respond to the world in an unapologetic, intelligent way. Belmore speaks to me in Anishinaabemowin, without using words.

When Nanibush became the first curator of Indigenous art at the AGO she had three artists—“my queens” she called them—that she wanted to secure prominent solo shows for: Rebecca Belmore, Shelley Niro and Faye HeavyShield. It is mind-blowing to me that this hadn’t already happened given their decades of artistic production, their international influence and the sheer integrity of their work. But we all know why. Nanibush nods as she explains that the statistics show that artists who are Indigenous women are lower-paid and have fewer shows, in less prestigious places. In this context, Belmore’s solo show this summer at the AGO is a victory for all of us, particularly those emerging and mid-career Indigenous artists making in the wake of Nanibush’s queens.

Nanibush explains that she’s learned a lot from working with Belmore, particularly about how to curate space as material. I’m drawn to the idea of transforming colonial space into decolonizing space, and so I think about my body, my presence and my surroundings as material as well. She talks about how Belmore’s work is concerned with violence, but that it takes us elsewhere, it doesn’t stay in the pain. It affirms our truths, but it is also generative. More intimately, she talks about learning how to carry herself from watching Belmore.

This is also something I’ve learned from Belmore’s work—the carrying of one’s own body, one’s own essence into (colonized) spaces. Belmore carries herself into spaces in an unapologetic, foundational way. This is significant to me because colonialism rips Indigenous peoples away from land, language, culture, family, away from our own knowledge system and away from the ability to feel at home in our own bodies—our dispossession is expansive. Belmore refuses this dispossession. She attaches herself to her body as home and carries herself into whatever space she is in, as if she belongs, as if she is supposed to be there. Because of course she is, we are. She creates and holds a decolonial presence that gifts me with the feeling and experience of freedom.

By the time our food arrives, Belmore is telling us that she learned this from growing up in northern Ontario in the mid-1970s and coming to terms with race while attending high school in Thunder Bay. She learned to perform on a daily basis in public space, as those of us with experiences of colonialism necessarily do. Belmore though, does this in a way that is opaque and Anishinaabeg-coded. She reminds me of old kokums from Treaty 3 in the way she moves and interacts with the world around her. She is sovereign. She is home. We are here, working, making things on our land, as we have always done. No apologies. No compromises. No explanations. Make the work, release it into the world and then make more.

Indeed, that is exactly what these two kwewag are doing.

I ask Rebecca if her practice has changed over the years. She answers that she has become more “deliberate in her practice, less reckless,” but that she hopes the “recklessness reappears with aging”.

We laugh.

Nanibush explains the title for the retrospective. It shares the name of a performance Belmore made at Queen’s Park on Canada Day 2012, in which she wrapped a 150-year-old oak tree in brown paper, eventually binding assistant Cherish Blood into the layers disappearing her. Nanibush did not ask for permission to stage the piece there, and this refusal is significant. Without permission, Belmore faced the monuments of empire head-on—the literal ones like Queens Park, the Ontario Legislative Building, the University of Toronto, and the surrounding government buildings, museums, statues and monuments celebrating stolen land and colonialism, and the more obfuscated ones that manifest the violence of disappearance and erasure, and the bureaucratic, structured colonialism that cages Indigenous brilliance, for instance. She disappeared yet another Indigenous woman by carefully wrapping her in paper and repeatedly binding her to a tree “in layers of its own death.” I come to understanding Facing the Monumental as a foundation of Belmore’s practice. She faces, takes on and undoes empire, while building monuments of her own. Coincidently, but meaningful nonetheless, the show opens on July 11—the 28th anniversary of the beginning of the Oka Crisis.

Nanibush has been curating Belmore for over a decade and she talks about how how she has learned to trust Belmore and trust her process. She shares what is evident to most: Belmore is meticulous and thorough, and this requires absolute trust in her, and her process, right up until the last minute.

Belmore adds that “as an Indigenous woman, people don’t think I know what I’m doing.” That sentence sits between the three of us until it generates ridiculous laughter at the nature of that reality. Here we are: an established writer and academic, the inaugural Indigenous curator at the AGO and one of the most important artists of our time, just taking some time out of the struggle to poke fun at the colonizer, because he never thinks we know what we are doing. I ask Belmore if this bothers her, that perhaps people don’t see her and her body of work as a crucial site of knowledge production not just as a Anishinaabekwe, but as an established, highly influential, international contemporary artist.

Rebecca Belmore, Mixed Blessing, 2011. Hair, plaster of paris, hoodie. Dimensions variable. Musée des Beaux-arts de Montréal, purchase, Louise Lalonde-Lamarre Memorial Fund.

Rebecca Belmore, Mixed Blessing, 2011. Hair, plaster of paris, hoodie. Dimensions variable. Musée des Beaux-arts de Montréal, purchase, Louise Lalonde-Lamarre Memorial Fund.

Belmore has too much humility to entertain my question. Instead she talks about Mixed Blessing (2011)—an image of which appears on the cover of my book This Accident of Being Lost—and how the figure is wearing a black hoodie with the intersecting words “Fucking Artist, Fucking Indian” in the crosshairs. She talks about how we are targets, and also about how being a badass Indigenous artist is an awesome and joyful thing, full of responsibility. Fucking Artist! Fucking Indian! “The role of an artist is a worker, art-making is a job,” she says. “I am the artist amongst my people. Every society has its artists, and we have the responsibility to speak about how we are collectively in this moment in time. We have the responsibility to carry the past and look towards the future.”

This makes me think of her 2002 performance Vigil, which commemorated the missing and murdered of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. She begins by cleaning the space on her hands and knees, much like we clean our ceremonial spaces. She lights candles. She nails the long red dress she is wearing to a telephone pole, struggling to free herself. When she eventually does just that, she names each of the women and shreds a flower in her teeth. Speaking of the work, she simply says, “I occupy space and make something in front of people.”

She continues, “They think as an Indigenous woman I don’t have an opinion about everything. I do. ” She gestures towards an experience familiar to Indigenous peoples—the restriction of our knowledge production and our influence to the local or into confined Indigenous spaces, or to “culture” rather than it being positioned as affecting—not just for Indigenous peoples, but for the world. Anishinaabe people are always international in thought and scope. Belmore turns to Fountain to illustrate her point. Fountain was Belmore’s contribution to the Venice Biennale in 2005. The politics and production of the work is layered. The piece is teeming with Anishinaabe sensibilities. There is a larger, clear, universal message as well. Belmore explains to me the piece is about water and blood in a global sense, in a way that perhaps has become more urgent in the years since with crises like Flint and Cape Town.

Water as life.

Running out of water.

Stealing water.

Fighting over water.

Water as lifeblood.

Water as blood.

Fountain is set to be installed in “Facing the Monumental,” and in context with this (new) urgency. We talk about how it has taken a while for the public to learn to read Belmore’s work as at once informed by being Anishinaabeg but commenting and speaking to the global. Nanibush points to Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside) (2017)—the marble wiigiwaam that was part of Documenta 14 in Athens in 2017. Anishinaabeg life is one of kinetics and creation. Our people make homes, ceremonial spaces and teaching lodges out of the materials available to us. It seems fitting that this wiigiwaam in Athens would be made of marble. But this monument is not just about us. It is also about displacement and dispossession, the making of migrant peoples, the people who are forced to make homes out of tents or tarps or whatever materials are available to them. Tent cities are made out of crisis and protest. And home is made, sometimes, out of one’s own body.

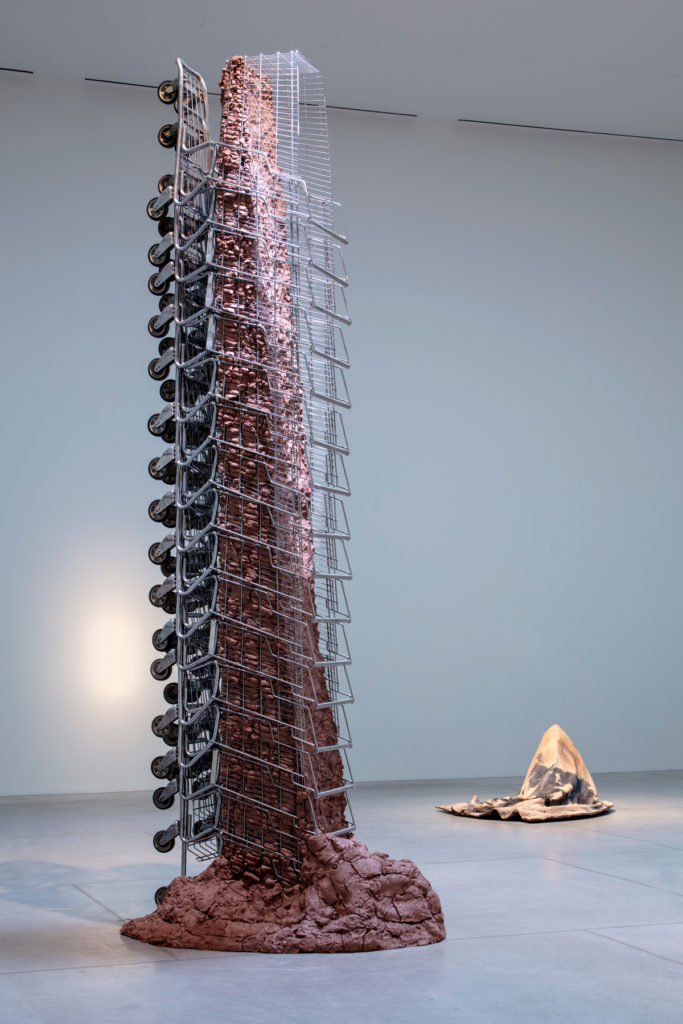

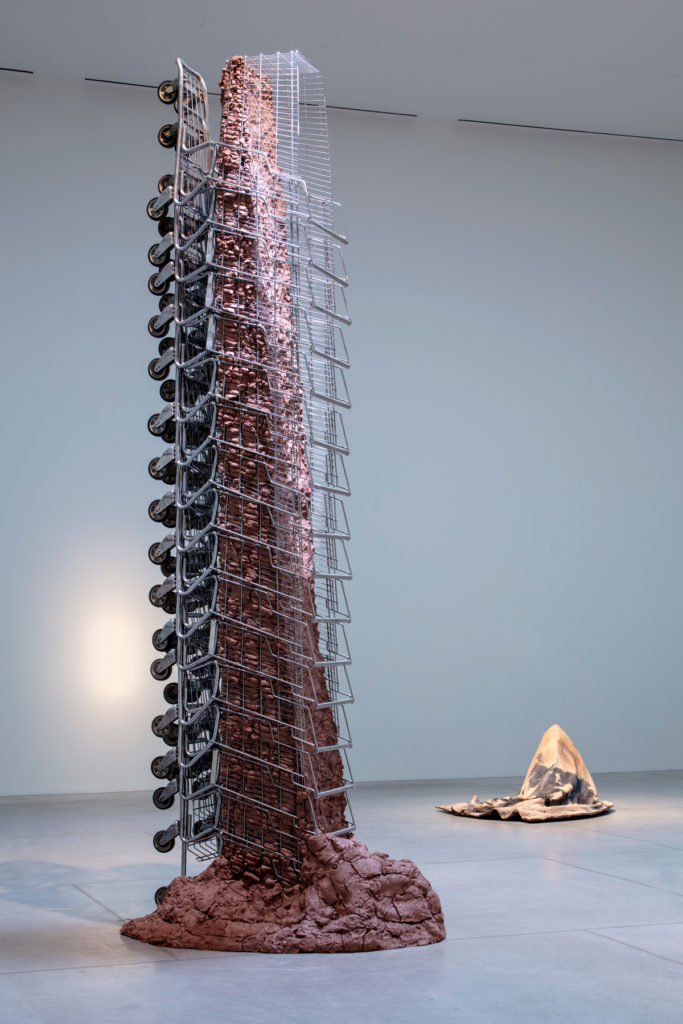

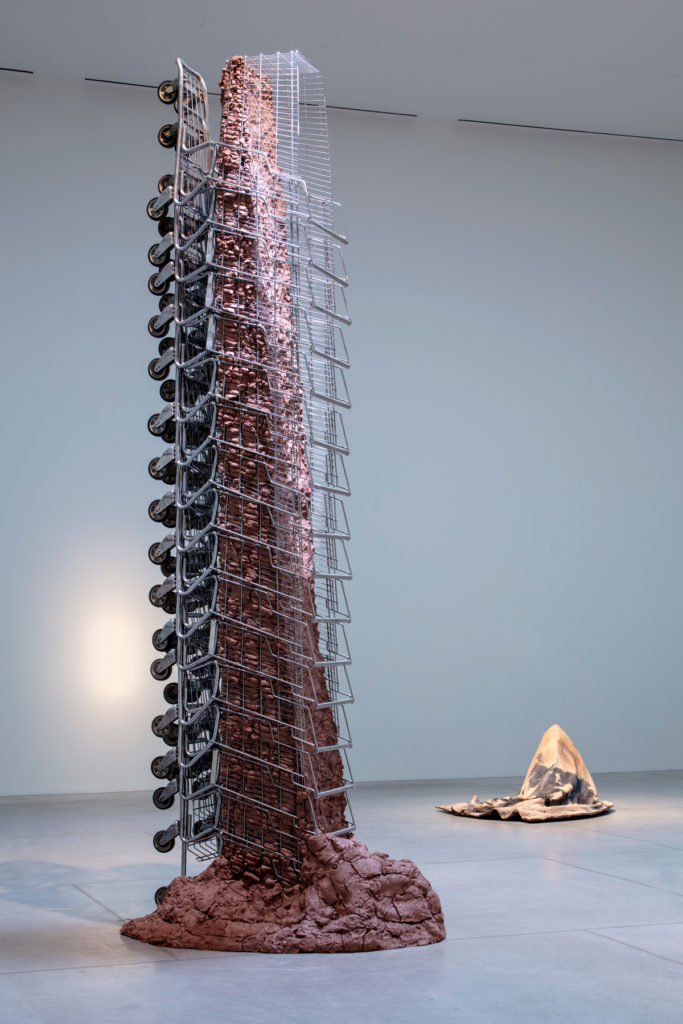

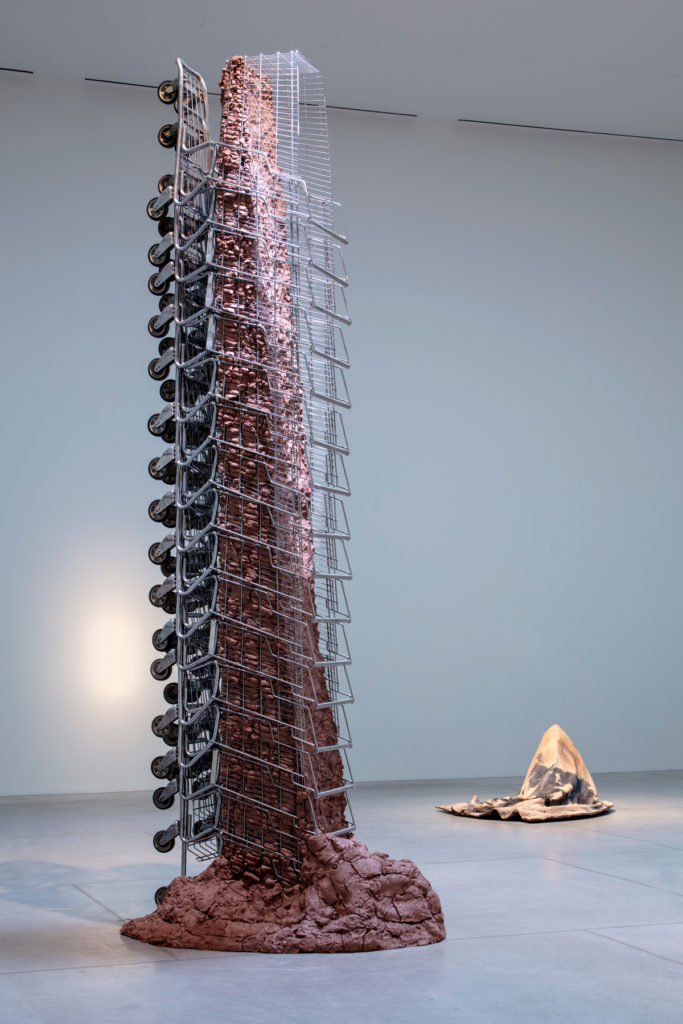

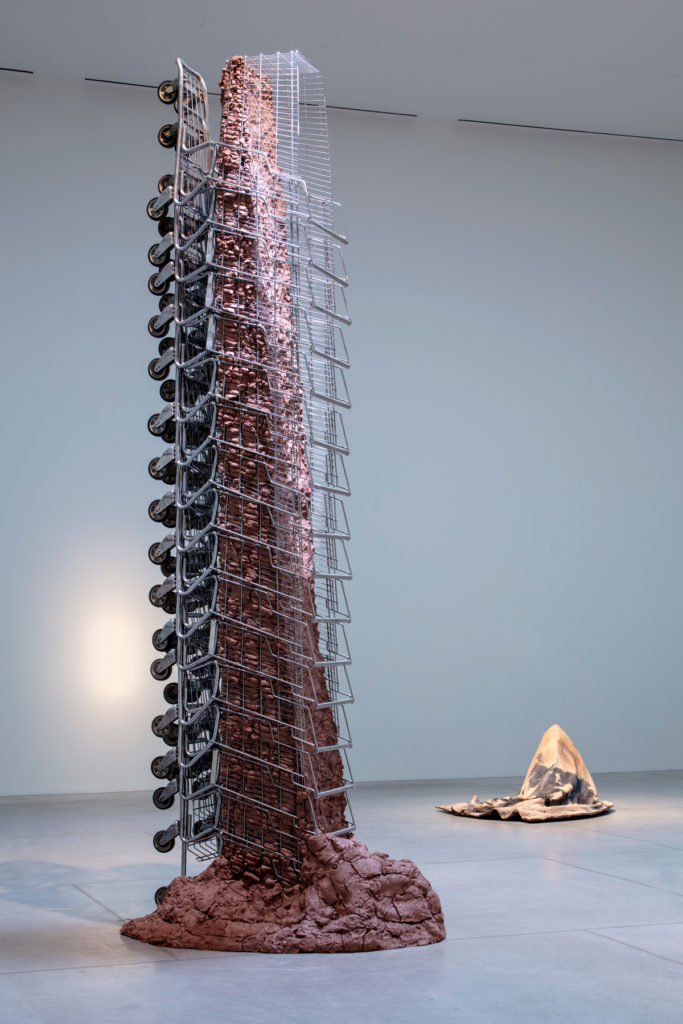

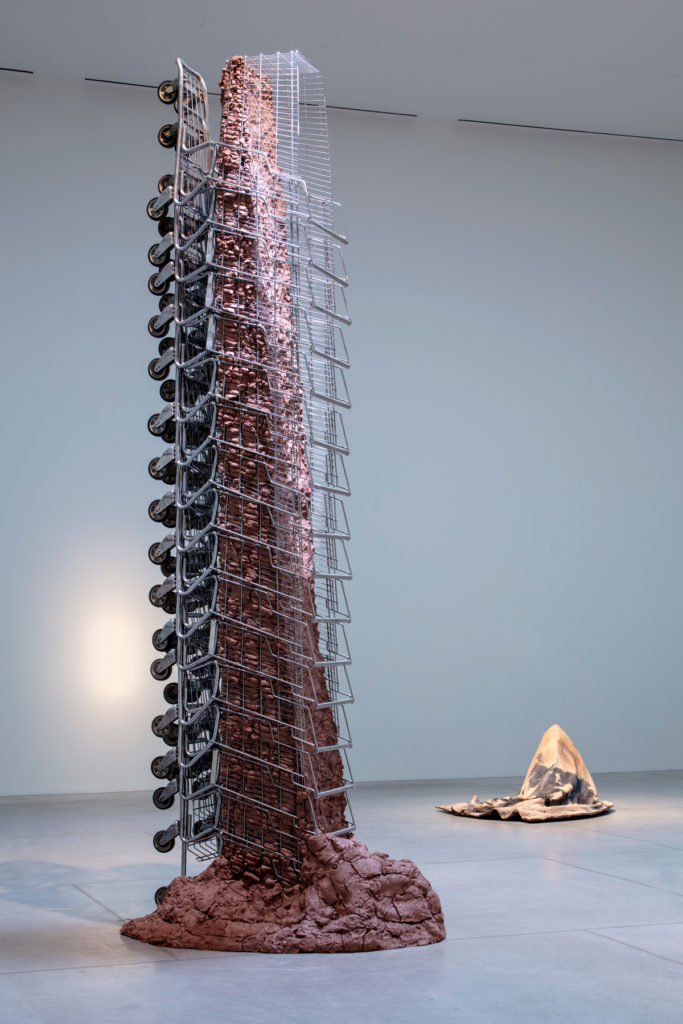

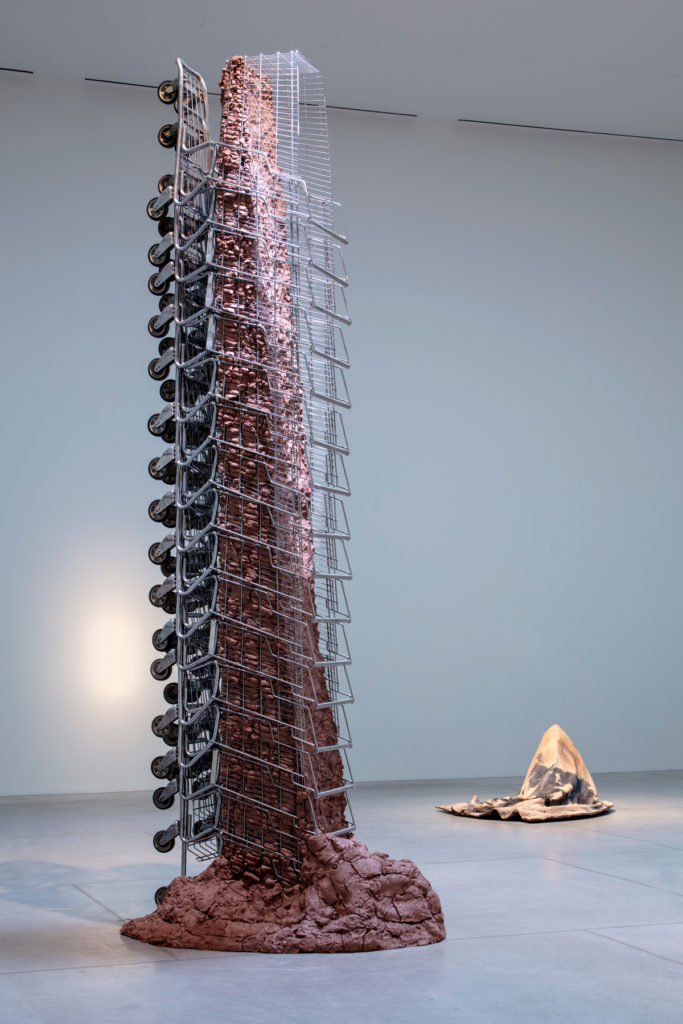

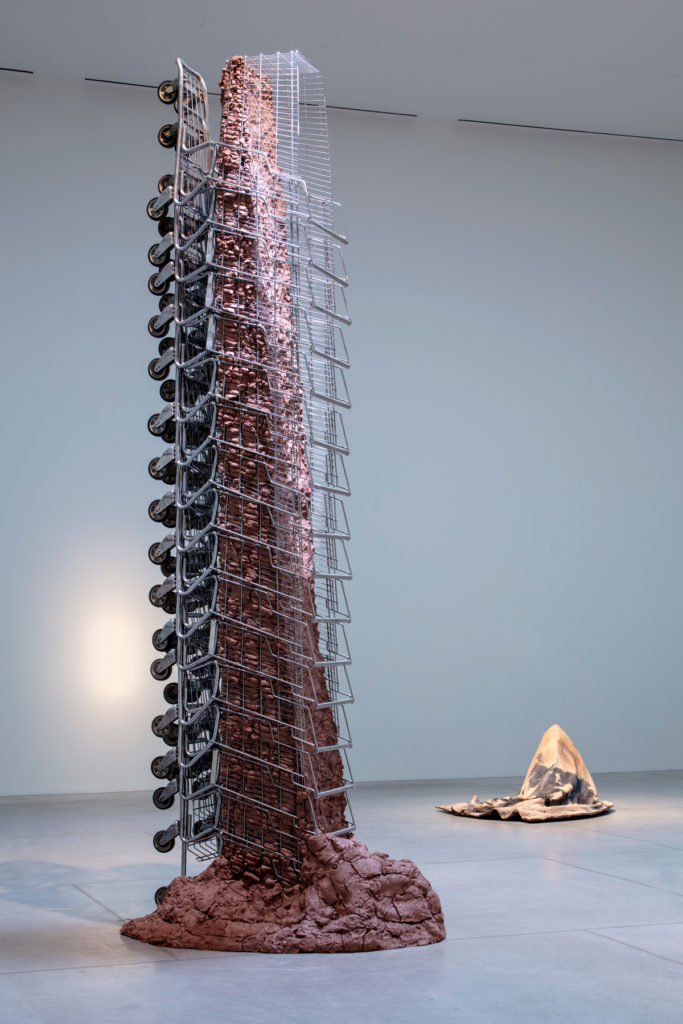

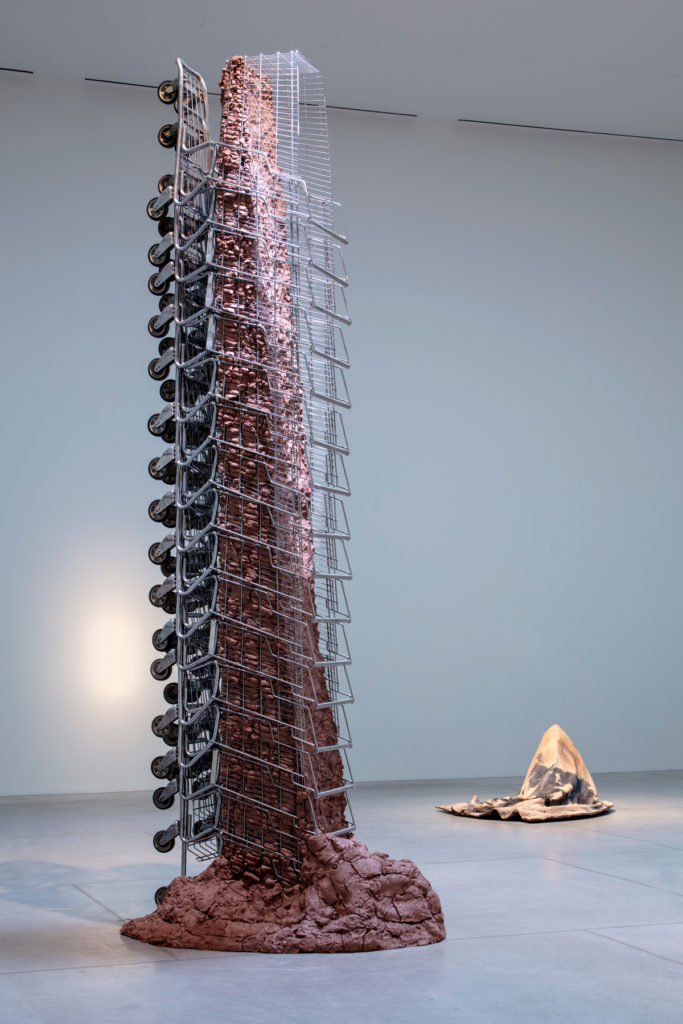

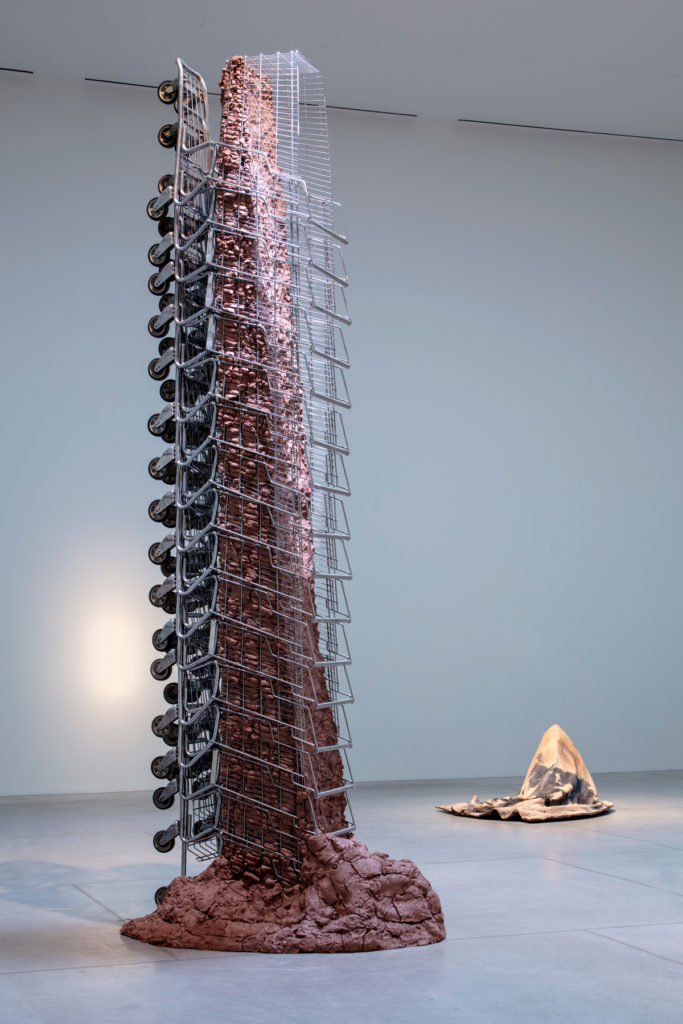

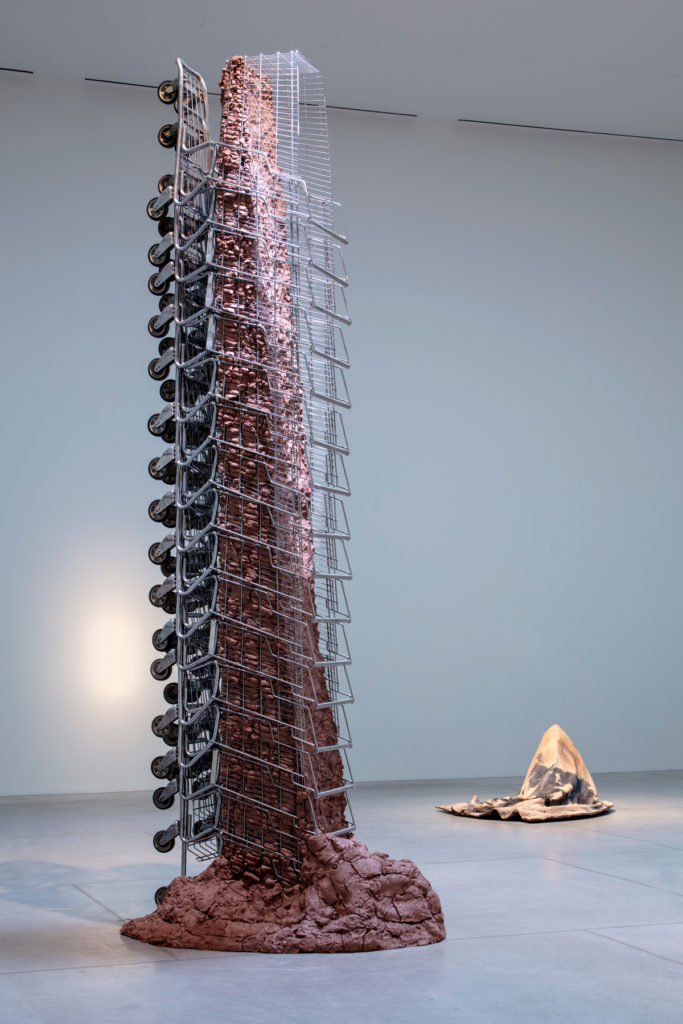

This leads into a discussion of tarps, which have shown up in both of our work, because of their utility, their inexpensive nature, their versatility and their aesthetic and material presence in our community. Belmore explains that one of her new sculptures is a blanket-sized tarpaulin made out of ceramic clay sourced from beneath the city of Winnipeg. From afar, it looks as if a figure is resting under the tarp, but as the viewer approaches, the tarp is empty. This work, titled simply tarpaulin (2018), is one of two new sculptures in the show. The other is Tower (2018), a 17-foot-long grouping of shopping carts that has been turned on its side into its titular form. The shopping carts are filled with clay.

I like that these two monuments will be installed in Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg territory. I like that Belmore comes to this city of Toronto and sees me and my people here and builds monuments to our presence, our life and our freedom—even those of us who struggle to find shelter in the urban. I like that she builds the monuments through which we can crawl towards the sky, even if bound by hand and ankle. Even if. Even if.

“Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental,” at the Art Gallery of Ontario, closes October 21, 2018.

Rebecca Belmore, Tower, 2018. Clay and shopping carts. Installed at the Art Gallery of Ontario. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, tarpaulin, 2018. Installed at the Art Gallery of Ontario. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Fountain, 2005. Single-channel video with sound projected onto falling water, 274 cm x 488 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Rising to the Occasion, 1987–1991. Mixed media, 200 x 120 x 100 cm. Gift from the Junior Volunteer Committee, 1995. Art Gallery of Ontario © Rebecca Belmore. Photo: Craig Boyko

Rebecca Belmore, State of Grace, 2002. Inkjet on paper, 122 x 152 cm. Collection of the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Quote,Misquote,Fact, 2003. Graphite on cotton rag vellum, 45.7 x 134.5 cm. Agnes Etherington Art Centre. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2008. Cibachrome transparency in fluorescent lightbox, 81.5 x 244.8 x 16.7 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Purchase, 2011. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Wave Sound, 2017. Banff National park, Alberta, Pukaskwa National Park, Ontario, Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland. Aluminum, dimensions variable. Installation at Art Gallery of Ontario. Commissioned by Partners in Art for LandMarks2017/Reperes2017 © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Vigil (from The Named and the Unnamed), 2002. Digital video disk (DVD), projection screen, and light bulbs. Projection screen: 94.5 x 124.5 x 12.5 in. National Gallery of Canada © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Blood on the Snow, 2002. Fabric dye, cotton, feathers, chair, 610 x 610 x 107 cm. Installation view at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Courtesy the Mendel Art Gallery collection at Remai Modern, purchased with the assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Mendel Art Gallery Foundation, 2004. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, Biinjiya'iing Onji (From Inside), 2017. Hand-carved marble, 143 cm x 209 cm x 209 cm. National Gallery of Canada, purchased 2018. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, sister, 2010. Colour ink-jet on transparencies, 2.13 x 3.66 m (overall). Courtesy the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.

Rebecca Belmore, sister, 2010. Colour ink-jet on transparencies, 2.13 x 3.66 m (overall). Courtesy the artist. © Rebecca Belmore.