I mediate my anxiety with my phone, in turn causing my anxiety to amplify. I reach for my phone when I think of an email I have to reply to, when I think of a recent mistake I made, read a sentence I don’t understand or remember how much work I have to do. And then, my time scrolling through Instagram leads to new anxieties: I should be working, I should be eating healthier, getting more likes. I should be working.

It seems like the cruelest irony that we now turn to our phones, which arguably cause a good deal of our problems, to try to alleviate said problems. We use a heart rate as a password, daily steps as points towards a movie ticket, gain stickers for meditating. There are apps that track your sleep cycle and wake you up at an optimal time, forgetting, it would seem, that the glare of a screen before bed provably disrupts sleep.

At the end of the opening for “Worldbuilding,” which brings together four works of art using virtual reality at Trinity Square Video in Toronto, a wave of dread hit me from seemingly out of nowhere. I snuck a glimpse at my phone. Earlier that night, my friend Nyla posted a picture of me with VR goggles on experiencing Eshrat Erfanian’s Waiting for Rostam, the light in the room only hitting me. I made her promise not to photograph me when lying on a mattress on the floor viewing Yam Lau’s Out of This World, which was having technical difficulties (thereby saving me from any photos of me lying in bed with a 21st-century sleep mask on my head circulating on social media).

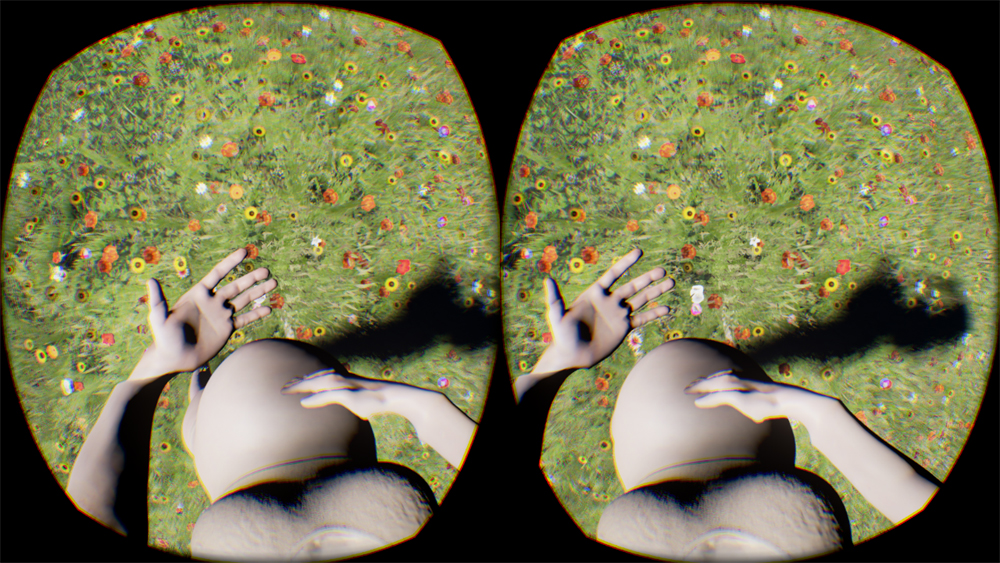

That sudden wave of anxiety was brought on by a conversation with Jeremy Bailey, whose VR piece Preterna was created with artist Kristen D. Schaffer, who is also his partner. Preterna simulates pregnancy by allowing the wearer to look down at their body (their avatar?) and see the addition of a pregnant stomach and breasts. Upon donning the VR headset—entering the art piece—you are transported into an idyllic meadow, complete with flowers moving in a breeze and birds chirping. In the distance there is a fellow pregnant woman, arms extended, scarecrow style. Bailey and Schaffer talk you through your new body and setting in an auditory artist statement.

Jeremy Bailey and Kristen D. Schaffer, Preterna (still), 2017.

Jeremy Bailey and Kristen D. Schaffer, Preterna (still), 2017.

Due to a glitch in the code, which Bailey and Schaffer address in the voice-over, it appears that your arms (your avatar’s arms?) are severed from your body. When I first put on the VR headset a friend moved me a couple steps over, causing the program to glitch further. Then, instead of being the pregnant woman with detached arms, I was standing next to her, like an image out of a horror film. I abruptly pulled the headset off (I’m easily spooked these days).

This accidental glitch accentuated the vulgarity of a technology that can morph your body into something it isn’t, or possibly never could be. (Unsurprisingly, most people I saw viewing Preterna throughout the night were men, embodying a position that would be impossible for them to recreate.) On re-entering the VR simulation I did not feel pregnant—there’s a huge gap between looking pregnant and being pregnant—but I appreciated the voice-over dialogue between Bailey and Schaffer that highlighted the inspiration behind the project: the conflict of partners who disagree about wanting children. I was skeptical at first about a meadow and billowing breeze as an overly saccharine representation of pregnancy, but the spouses’ commentary between highlights the irony of the project; you begin to realize the birds are actually crows.

Talking with Bailey after experiencing Preterna, he told me, “According to Marx, capitalism is an exploitation of the body. This used to be in the form of violence against the body, factory workers dying on the job. Now this exploitation is also cultural: the body is appropriated, or gender, emotions are appropriated.”

Jeremy Bailey and Kristen D. Schaffer, Preterna, 2017. Installation view at Trinity Square Video. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Jeremy Bailey and Kristen D. Schaffer, Preterna, 2017. Installation view at Trinity Square Video. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

VR can tap into this exploitation, appropriating our bodies by re-imagining them completely. In the sphere of VR, bodies no longer belong to the physical realm, but instead become avatars of the artist’s creation. The body participates in the artwork, visually taking on a new role or place in time. Looking pregnant may be different from feeling pregnant, but entering a VR work that places your body into a new one is enough to make you feel detached from yourself.

None of the works in “Worldbuilding” take advantage of these body-monitoring technologies more powerfully than Erin Gee’s VR game Project H.E.A.R.T., made in collaboration with Alex M. Lee. Floating above an animated battlefield, the viewer becomes the holographic pop star Yowane Haku. The premise of the game is to channel “genuine” enthusiasm and empathy towards the soldiers down below as a salve against PTSD. The game tracks your heart rate and perspiration using a biosensor: the more excited you are, the more soldiers your avatar is able to save.

Erin Gee with Alex M. Lee, Project H.E.A.R.T., 2017. Installation view at Trinity Square Video. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Erin Gee with Alex M. Lee, Project H.E.A.R.T., 2017. Installation view at Trinity Square Video. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bailey’s articulation that technology has become a bodily intervention is literalized in Gee’s project. With the use of biosensors, our bodies become an extension of the game. This is similar to how phones—mindfulness apps, step counters and sleep trackers—mine our bodies for data that is translated into statistics and then marketed to us as a guide to self-improvement. The gamification of our bodies renders the physical form void, replaced by screens where our bodies and emotions can be morphed and manipulated. Perhaps the only way to create art with technology as advanced and recent as VR is to reckon with its potential consequences.

Gee’s project, the most realized out of the four artists in the exhibition, masters this reckoning. I spoke with Gee in the lead-up to the exhibition, and she explained the conceptual backbone of the piece. “I’m working through questions of emotional sincerity when it comes to self-help. In theory, if you can technologically master your emotions, if you can just make yourself excited, then you can make yourself a better, happier person. I don’t know how sincere that is, because real life isn’t always a string of happy events.”

“A lot of [being able to control your emotions] is marketed to people as: if you have excellent mental health, you must be a morally excellent person and be very successful. And there’s something very capitalistic about this. With anxiety levels on the rise, I can’t help but see that this is probably tied to the economy.” Gee continues, “I feel like a lot of these soldiers [in the game] are saying things that people can relate to. When you approach them they say things like, ‘Am I motivated enough to follow my dreams?’ or, ‘Your sincerity is inspiring me.’”

Erin Gee with Alex M. Lee, Project H.E.A.R.T (Holographic Empathy Attack Robotics Team) (still), 2017.

Erin Gee with Alex M. Lee, Project H.E.A.R.T (Holographic Empathy Attack Robotics Team) (still), 2017.

Project H.E.A.R.T shares a particular irony with Preterna. It uses the tropes of wellness and makes them hyperbolic in an attempt to make the viewer aware of the absurdity of it all. When I was young, maybe 13, I went to Camp Olympia for triathlon and competitive-swimming training. I did not have a good time—perhaps that’s an understatement. The cold lake water was giving me headaches, I got my period for the first time, I didn’t have any friends.

I spent a lot of time at Camp Olympia in the HeartMath lab. The lab was filled with PCs connected to wires that tracked your heart rate, and on each computer was a game that allowed you to float through clouds: the calmer your heart rate, the better you did. So I would sit in this computer lab, at sports camp, and hold my breath to try to game the system into giving me a better score.

Gee is right: even if you can trick technology into thinking you’re happy or excited, it’s not extended to emotional sincerity, and it doesn’t necessarily make you happier. I was not happy at camp, and my phone and all of its self-help apps do not make me happy now.

Tatum Dooley is a writer living in Toronto.

Yam Lau, Out of this World, 2017. Installation view at Trinity Square Video. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Yam Lau, Out of this World, 2017. Installation view at Trinity Square Video. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.