The title of American photographer Taryn Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and other Chapters I–XVIII refers to a landowner in the Indian province of Uttar Pradesh forced to leave his home after learning that his death certificate has been processed by officials bribed by relatives in line to inherit the property. The legal case to right his falsified death—which, according to the exhibition’s text, is apparently unexceptional in the province—is many years deep into the purgatory of the local judicial system.

In her project, Simon explodes this man’s narrative into a totalizing index that traces the bloodlines of his family and several others. Rich with systems and sequencing, A Living Man Declared Dead and other Chapters I–XVIII charts linear chronologies of ascendency or inheritance against the friction of an organic logic whose tenets are arbitrary but inflexible: blood, birth and death. The unforgiving rigour of Simon’s methodology surfaces deep incongruities between the politics of territory, religion, history or power and the raw material of the human body.

This work is divided into 18 chapters; 9 are on display in the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Each chapter consists of a stylized investigation into a bloodline originating from a single individual, including a Kenyan healer known for treating illnesses ranging from evil spirits to HIV/AIDS (he is sometimes paid for his services in wives) and the first female ever to hijack a plane. Other bloodlines include early Israeli settlers, Australian lab rabbits infected with a disease intended to eliminate their wild counterparts, and a Chinese family selected by the government specifically for representing “a typical Chinese family” in Simon’s project.

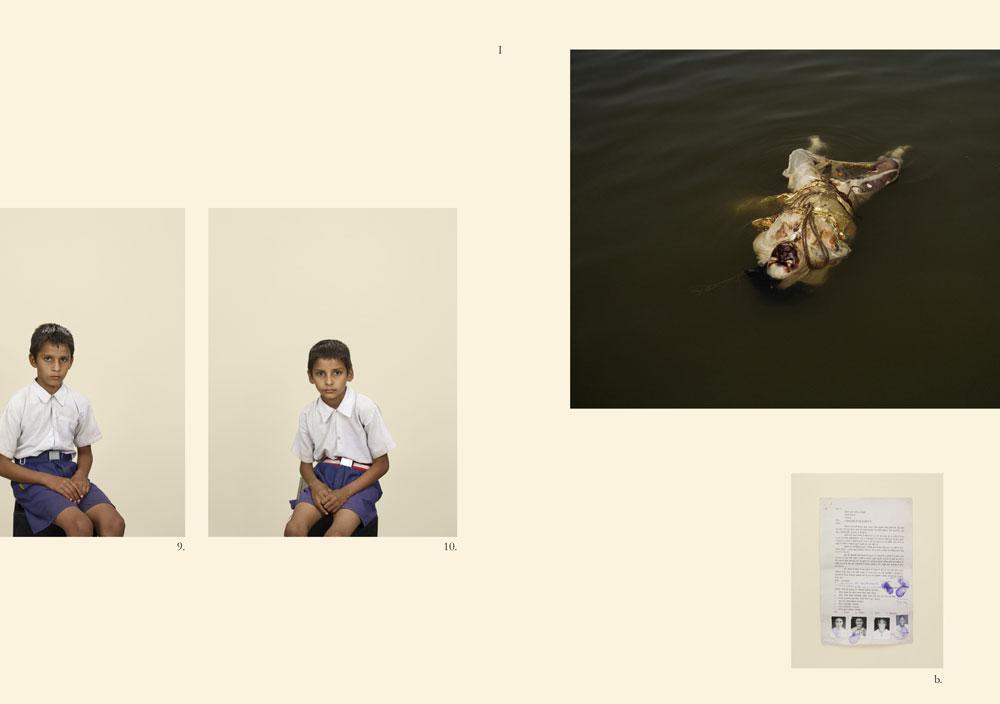

Each chapter is presented as a triptych. A left-hand panel displays rows of identically contrived portraits—a single subject sitting facing forward against a white backdrop—sequenced according to a formula of Simon’s design, published as a part of the exhibition’s didactic text, that allows viewers to read a bloodline from left to right. Several chapters include blank portraits to represent the absence of those who were unable or chose not to participate. In one chapter detailing the living history of a Bosnian family whose numbers shrank dramatically during the war of the early 1990s, photos of identified and archived remains collected from mass execution sites stand in for the presumed or confirmed dead.

A central panel provides a corresponding inventory of name, age, birthdate, location and occupation for each individual in the portrait grid. For those not pictured, a terse explanation is given for their non-appearance: some have declined on social or religious grounds; others could not be traced.

The right-hand panel hosts photographs of other material pertaining to a given bloodline’s narrative, supporting documents to Simon’s totalizing index. While some of this tertiary information’s relevance is self-evident—legal documents, newspaper articles, diary entries, cityscapes—other images provide more obtuse contexts for a particular historical moment: the ornate, decaying interiors of a Ukrainian orphanage, or a shrouded leprous corpse floating down the Ganges. It is in these photographs that viewers have access to the style that characterizes Simon’s earlier work, such as An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar: rich and dense, immaculately calculated, deeply narrative, communicating intimacy like a secret.

In the photographs mounted in these third, final panels, Simon’s system is designed to accommodate even that which is outside of itself. Their relationships to the portrait photographs are not unlike the relationships between the chapters: occasionally obscure and aesthetically consistent, creating within the space of the installation an anarchic constellation of sympathetic histories edited to emphasize the inscrutability of the contemporary moment.

This latter effect is what distinguishes Simon’s deadpan cataloguing from an anthropological endeavour. Whereas the anthropological motive is to explicate, rationalize and simplify, Simon’s systems work in the opposite direction—towards complication, compromise and subtlety. In Simon’s work, rigorous research methodologies can only illustrate their own fallacies.

While the photographer’s choice of subjects occasionally falls somewhere between the sensationalist and the unimaginative—the African polygamist, the German Nazi, the Palestinian freedom fighter—their inclusion here can only serve to disrupt the idea of a popular narrative. And Simon’s role as a photographer—as an alien and a rearranger—is never made obscure. If anything, her attempts to aestheticize these narratives into universality show just how heavy the hand of any photographer is in the image-making process.

Taryn Simon Excerpt from Chapter I of A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII 2008–11 © 2012 Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon Excerpt from Chapter I of A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII 2008–11 © 2012 Taryn Simon