Provocation is not synonymous with social critique, as a glance at the contemporary-art section of any Sotheby’s auction catalogue will prove. Indeed, art that bills itself as “provocative” or “transgressive” is now so much a part of the ideological landscape of contemporary art that it is practically orthodox. As a result, “breaking taboos” has dwindled as a viable form of critique, and increasingly props up an inequitable and oppressive status quo.

For this reason, I usually avoid commenting on the work of Ottawa-based artist Jonathan Hobin. His previous body of work, which used young children to recreate disasters, threats and tragedies as diverse as 9/11, the murder of JonBenét Ramsey and the perils of nuclear war, seemed to court controversy for controversy’s sake, with a critique of the myth of childhood innocence merely serving as a convenient foil. And although In the Playroom (2010) often succeeded in outraging the conservative audience it seemed destined to annoy, in the final analysis it was no more disturbing than video games or Anne Geddes posters, and not as nuanced as other photographic projects tackling similar issues, such as Diana Thorneycroft’s The Doll Mouth Series (2004–05) and A People’s History (2008–12).

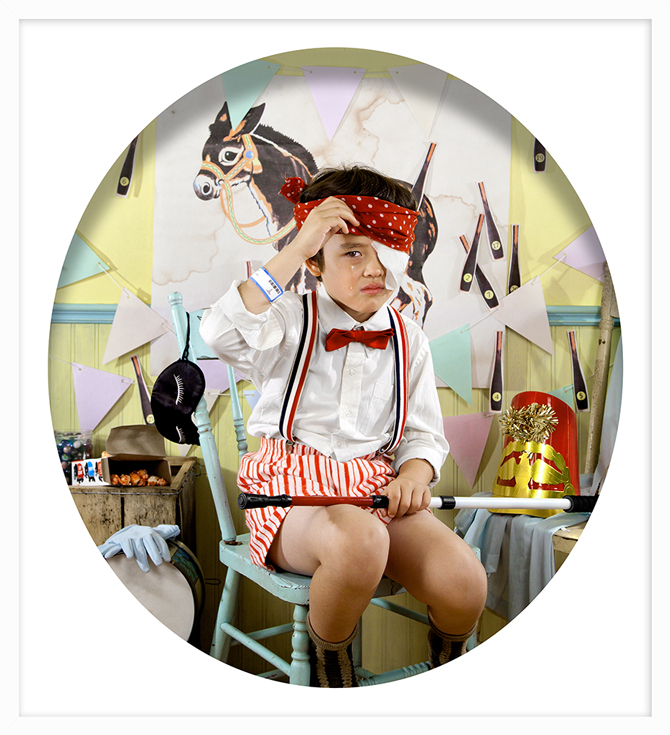

Hobin’s most recent body of work, however, finally delivers some content worthy of comment. Currently on display at the Montreal commercial gallery Art Mûr, Cry Babies (2015) features a series of cameo portraits of children dressed to personify an array of traumatic experiences, social stigmas and racial stereotypes. In Lonely Ranger, for instance, a white child in a cowboy costume cries while aiming a pistol at his open mouth. This photograph is presented alongside Honest Injun, in which another weeping child wears a kitsch headdress and clutches a bottle of Leinenkugel’s Chippewa Pride Beer. Meanwhile, a tearful white boy sporting blackface munches a watermelon (Pickaninny), while a disconsolate black girl dressed as a “mammy” confronts a stack of pancakes and a bottle of Aunt Jemima syrup (Aunt Mammy). To be fair, not all of these photographs deal with race—other works in the series tackle terminal illness, physical disabilities and gender identity—but the issue looms so large it warrants particular attention.

Ostensibly, Hobin’s work marshals the idioms of a particular kind of critical art, one that seeks to subvert oppressive stereotypes through grotesque exaggeration. The problem, as I see it, is that he has not fully considered the question of racial caricature, and particularly how it relates to his own social status as a white male. When Spike Lee made Bamboozled (2000), a satire centered on a televised modern minstrel show featuring black actors in blackface, he was critiquing both the contemporary and historical experience of blackness—an experience that was also his own. When Kent Monkman dons a headdress and stilettos to become his alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, he is exploding oppressive racial and gender stereotypes that he, a person of Cree ancestry, actually faces on a daily basis.

We must ask ourselves: What is Hobin performing through the image of a white child in blackface or a black child dressed up as Aunt Jemima? If the answer is, as I think it must be, his white privilege, then his use of racial caricatures becomes less a form of social critique and more a modality of appropriation, one that co-opts the political struggles of oppressed and marginalized groups in the name of provocative art. While I am critical of this approach, I cannot help but note that it also raises some rather important questions. For example: Can white people legitimately participate in an ironic critique of racial stereotypes borne out of white-supremacist ideologies? Or does any such critique merely amount to the co-optation of artistic strategies necessarily grounded in an actual experience of systemic racism? While Hobin’s work certainly doesn’t answer these questions, it nonetheless brings them to the fore, and herein lies its value.