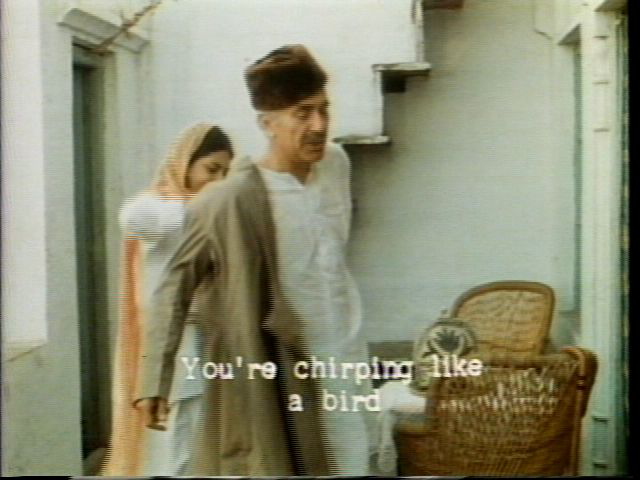

In M.S. Sathyu’s 1974 Indian film Garm Hava (Scorching Winds), the tremors following the Partition of India in 1947, as felt by the everyday, middle-class small-towner, are quiet. In the opening scene, Salim Mirza—a Muslim patriarch and business owner, caught in the tragic dilemma of leaving his home in Agra, northern India, with his family for Pakistan—sits in a horse cart to head to work. Gazing at the barren, decrepit streets, he says to the rider, “They’re uprooting so many flowering trees,” while removing his cashmere topi (skull cap) briefly to let his head cool. “They’ll wither in these scorching winds,” the rider responds.

In Garm Hava, gradual, scorching wind signals the mundanity of losing ground; it recalls the uncharacteristically dry warmth that, following 1947, often accompanied the post-partition refugee experience: parched journeys, blistering soles and days spent waiting on either side of the border.

The melancholy of the landscape in partition narratives could be seen as moments of pathetic fallacy, a literary trope where weather, animals and vegetation mirror and are attributed with characters’ sentiments. The flight of migrants, a physical relocation, imprints nature, fracturing the land and, often, destabilizing the earth’s patterns of survival.

The weathering landscape parallels migrant departure in “Yonder,” a group show—co-curated by Mona Filip and Matthew Brower at Toronto’s Koffler Gallery, now opened at the University of Waterloo Art Gallery—featuring 17 artists from all over Canada with works loosely themed on migration and translation.

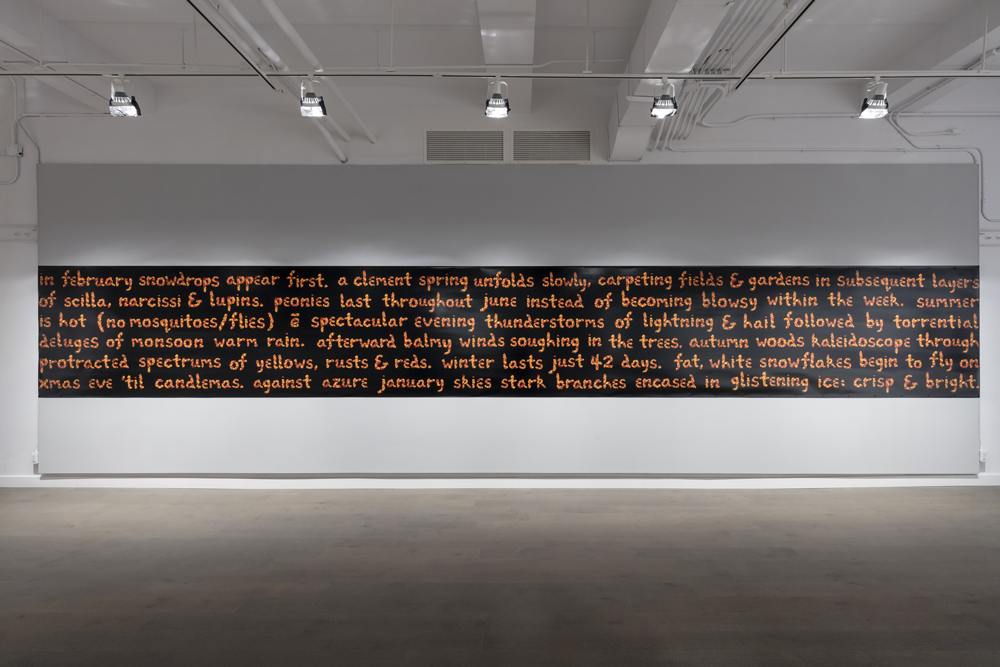

Sarindar Dhaliwal, Weather: an Immigrant Perspective, 2016. Chromira print. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Sarindar Dhaliwal, Weather: an Immigrant Perspective, 2016. Chromira print. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The fallen flowers struck me first. Sarindar Dhaliwal’s Weather: an Immigrant Perspective (2016) is part of the cartographer’s mistake, a larger project by the artist. Here, Dhaliwal has picked plump marigold clusters to construct text, which is then photographed and printed on a black surface. The font seduces, reading like a colonial travelogue: “in february snowdrops appear first. a clement spring unfolds slowly, carpeting fields & gardens.” Marigolds, at once uprooted yet ornamentally laid on the ground, become purveyors of collective trauma, mourning the lives separated and lost by the colonial construction of the Indo-Pakistan border. Dhaliwal’s text reads as both poignant and predatory. She fictionalizes narration by Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who, in 1947, created the Radcliffe Line that divides India and Pakistan. The British cartographer, here, is a racially neutral, genderless force, reincarnated as a bird to undo his past life’s colonial wrongs.

Marigolds, objects of both celebration and memorial in the Indian subcontinent, and the words they craft, come across as darkly comic, gentle reparations of the wandering, white man.

Jérôme Havre, Poetics of Geopolitics, 2016. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Jérôme Havre, Poetics of Geopolitics, 2016. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The flowers also appear contorted and elongated when reflected in mylar on the adjacent wall, a part of Jérôme Havre’s installation Poetics of Geopolitics (2016). In the installation, Havre deconstructs his sense of place and identity through a sterile meditation on the relationship between the earth’s geography and modern bureaucracy. A neon-red streak of light mimicking the tectonic fissure between South America and Africa is positioned across the mylar wall, striking the viewer’s reflection of themselves. To its right is a framed display of the artist’s two passports (during my visit, one of the passports was removed for Havre’s travel purposes), next to which are two nearly-identical wooden,, rectangular sculptures painted with TV colour-test patterns, hanging by straps like briefcases. Thick black stripes alternating with white are painted on them, the monochrome laden with horizontal strips filled in with bright colour. At first, the object looks like a cross between a briefcase and a TV set. I later looked at the lines of colour weft against black print, and noticed what seems like a conveyor belt carrying luggage.

The cold, muted metallic tones recall the site where home can feel most unstable: the airport. Viewers looking at their twisted reflections on the glinting surface, while also assessing Havre’s materials, begin to resemble passengers. You see yourself here, like you do in lines for customs, along random security checks, against baggage carousels. You anxiously judge and scrutinize yourself, you wait.

“Yonder” (installation view), 2016. Courtesy Koffler Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

“Yonder” (installation view), 2016. Courtesy Koffler Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

When you’re sitting on a plane during turbulence, there are times when the cabin floor feels like it’s falling from below your feet. Within seconds, you find your feet, and your heartbeat feels more intact. Before this happens, you feel a weightlessness, a capacity for flight.

Alfred Hitchcock, The Birds (still), 1963.

Alfred Hitchcock, The Birds (still), 1963.

Flight is tied to the ground left behind. The illusion of inertia felt on a plane often numbs the passenger, and its possibility for destruction is a threat to those on land. The alien capacity to fly preludes danger in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), where crows mysteriously attack people walking on the streets in Bodega Bay, California. Without ground to permanently perch on, the maddened figure of the bird is a flying, dangerous “other” for the film’s white-only characters; no human being can make sense of it.

When I first approached Jinny Yu’s Don’t You Like Us? (2016)—a sound installation that remixes and loops audio from Hitchcock’s The Birds—at the staircase by the door, steps away from Koffler’s main gallery space, I came across a sign. It was at the foot of the stairs, and warned, “This includes sounds of screaming and running, as well as monologues expressing fear. If you do not wish to experience it, please use the elevator…”

Yu’s looped-audio installation (not presented at a staircase but rather in a vestibule entrance to the visual-arts department at the UWAG, with two speakers overhead) requires the viewer to climb up and down two flights of stairs, filled with frantic sounds of Hitchcockian terror. Hearing the protagonist Melanie Daniels’s screaming voice, for once without the visual of Tippi Hedren’s fluffy blonde hair and stately, sharp nose, disarms the senses, and exposes the premise of many horror films: the (white) woman’s socialized terror of the often racialized other. By eliminating the visual of the fearful, white body, and placing only her sounds of fear, Yu makes those afraid in Hitchcock’s horror film seem equally dangerous.

Through the absence of image, Yu conceives the noise of xenophobia. Her birds are freer, less alarming, more determined to seek home than those in The Birds. They speak, but are invisible, overshadowed by the noise of human hysteria. They are migrants, rarely invaders.

Julius Poncelet Manapul, Balikbayan Bakla Maya, 2016. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Julius Poncelet Manapul, Balikbayan Bakla Maya, 2016. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Birds feature continually in “Yonder,” as symbols of both diasporic flight as well as the colonial gaze. They are rendered closest to flesh, however, only in Julius Poncelet Manapul’s Balikbayan Bakla Maya (2016). This mixed-media installation suspends paper cut-outs of Maya birds, exotic to the Philippines, from the ceiling, as they hover above a cardboard “balikbayan” box, which refers to care packages Filipino/a migrants send back home as both remittance and gift. Most of these birds are frozen mid-flight around a white birdcage that hangs above the work. Some, however, seem to emerge (along with 26 butterflies crafted from paper clippings) from within the box, peeking out of its perfectly rounded holes, their paper wings cut precisely to replicate feathers.

Manapul rejects the idea of the migrant as simply a corporeal being, choosing instead to craft a diasporic spirit, armed with the body’s many remains, absences, desires and shame. In place of the three toes typically found on the feet of the passerine birds are Manapul’s own fingernails; thin and tiny and insignificant, they pierce the air like talons, the birds swaying lightly. The birds and butterflies themselves are queered, constructed from printouts of online-sourced gay porn (“bakla” means “queer”). As the didactic mentions, these creatures are symbolically (and visually), “castrated.” The box that they seem to spring out of is plain and white. It reads, “BALIKBAYAN,” in black text. “Balik” means to “return,” and “bayan” means “village or country.”

Divya Mehra, There are Greater Tragedies, 2014.

Divya Mehra, There are Greater Tragedies, 2014.

What does bodily desire have to do with the likelihood of return? Who gets to leave, when, and on what terms? Where does the ground lie, and how do you lose it? What does it mean to traverse, to fly, to leave behind, queer, turn, return?

Exiting the gallery, I see Divya Mehra’s There are Greater Tragedies (2014) for the second time. Hoisted by the main entrance outside Artscape Youngplace, Mehra’s installation, a black flag crafted from 70-denier high-tenacity nylon, reads in white text: “MY ARRIVAL IS YOUR UNDOING.” Although the fabric waltzes in the wind, flying away from the pole, the work embodies a permanent fixture, a mark of being rooted to this ground. The monochromatic text is threatening, bleakly confrontational. One is haunted by the sense that this flag exposes an invisible border that only thinly veils—the distinctly Canadian, and ongoing—white-supremacist terms of occupation and entry on stolen land.

Mehra’s installation seems to expect an impending arrival, conjuring, for me, a port that first sights a boat filled with bodies approaching its shore.

In all of the works, flight from land, often the only option, feels intimately bound to the site of departure. Visions of a “yonder home” undo immigrant arrival, and choose, instead, to inhabit ground. They pull attention away from the bodies that leave home and (invisibly) return, and draw it instead, towards the earth, warmth and air that respond to and witness their movement.

Before landing, you discover a stillness in flight. The land you glide toward, and eventually set foot on, even momentarily, begins to feel like a home. This ground carries remnants of many like you, stray and saint alike. But whose ground are you on? And how did you find it?

M. S. Sathyu, Garm Hava (still), 1974.

M. S. Sathyu, Garm Hava (still), 1974.