The recent exhibition “The Keeper” at New York’s New Museum engaged the act of collecting and preserving objects along with the ideas they embody; included was the massive 2002 installation Partners (The Teddy Bear Project) by Canadian curator, collector and artist Ydessa Hendeles. Though Hendeles’s noted Toronto project space shut its doors in 2012, “Death to Pigs”—on at Barbara Edwards Contemporary in Toronto until December 10—provides a more intimate take on historical dystopian themes and their resurgence.

Swapping symbols ursine for porcine, Hendeles’s historic meditation is as much about the past as the present. As the show draws on uncomfortable histories like the Manson Family murders, I can’t help noticing the ideas embodied in Hendeles’s chosen objects echoed in recent electoral dystopias and Netflix’s social-media critique Black Mirror.

“We revel in cruelty…it’s a weakness that should be bred out of us,” says a hacker’s angst-ridden manifesto in “Hated in the Nation,” the final episode of season three of Black Mirror. The episode follows DCI Karin Parke and her partner Blue Colson in pursuit of a hacker who reprograms synthetic bees, developed to replace the extinct species, into weapons that bring accountability to Twitter trolls using the #DeathTo hashtag. Tweeting #DeathTo at a controversial journalist, a musician and a young woman who drunkenly urinated on a monument quickly turns into death to and for the tweeters. In its sprawling tales, Black Mirror functions as a dystopian satire of our techno-centric world, with brief visions of fleeting utopias on the brink of collapse.

As the episode illustrates, social-media platforms like Twitter offered an almost-utopian platform for global exchange when they were first launched, but they soon became places for violence. There is no shortage of racist, sexist, xenophobic and homophobic content alongside genuine exchanges of information. The distance and anonymity between users ultimately turned the Other into an account, handle or invisible code too distant and unreal to consider human.

Hendeles historicizes these “constructive forces” and their ultimate decline into “destructive ends.”

Ydessa Hendeles, Nose, 2015. Seven pigment prints on archival paper, framed in hand-painted white poplar frames, 46 5/8 x 55 5/8 x 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Nose, 2015. Seven pigment prints on archival paper, framed in hand-painted white poplar frames, 46 5/8 x 55 5/8 x 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Tracing the flickering line of (in)humanity, Hendeles asks: To what extent does “pig” signify immoral or unfavourable traits? Both Islam and Judaism cast pigs as unclean and unfit for consumption; the exhibition notably opened during the Jewish High Holy Days. After murdering the LaBianca family, Charles Manson and his followers scrawled “Death to Pigs” in blood on the walls of the household. This call against the immorality associated with the animal gives the exhibition its name. We use “pig” to insult law enforcement and those we consider slovenly. We even put our money in swollen and inflated “piggy banks.” “You’ve called women you don’t like ‘fat pigs,’ ‘dogs,’ ‘slobs’ and ‘disgusting animals,’” Megyn Kelly said to Donald Trump during the first Republican debate. “Only Rosie O’Donnell,” he replied with a smile. I wonder if anyone would admit their spirit animal is a pig?

Though the term “pig” is used to degrade, the children’s story of the Three Little Pigs features characters that outsmart the wolf pursuing them. Even movie-star pig Babe reflects traits of humility and bravery rarely associated with the species. So does the term represent a state of authority or subjugation, veneration or disgust?

Engaging literature, furniture, painting, anatomical models and children’s toys, Hendeles responds with a constellation of latent meanings—often uncomfortable, poignant and disturbing as they unfold.

Ydessa Hendeles, Sow (1904), 2015. One black-and-white and two colour pigment prints on archival paper, with custom blind deboss, mounted on museum-board, in ebonized ash frames. 32 3/4 x 88 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Sow (1904), 2015. One black-and-white and two colour pigment prints on archival paper, with custom blind deboss, mounted on museum-board, in ebonized ash frames. 32 3/4 x 88 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Sow (1904) (2015) features three enlarged panels from L. Leslie Brook’s The Story of the Three Little Pigs published by Warner and Co. in 1904, with Hendeles intentionally removing the remaining images from the book to emphasize the metaphoric journey of a single pig.

“The pig here has distinguished herself by learning to walk on two legs,” Hendeles writes in the accompanying notes. “She has found her feet to stand up for herself, survive the threat and do away with the predator.”

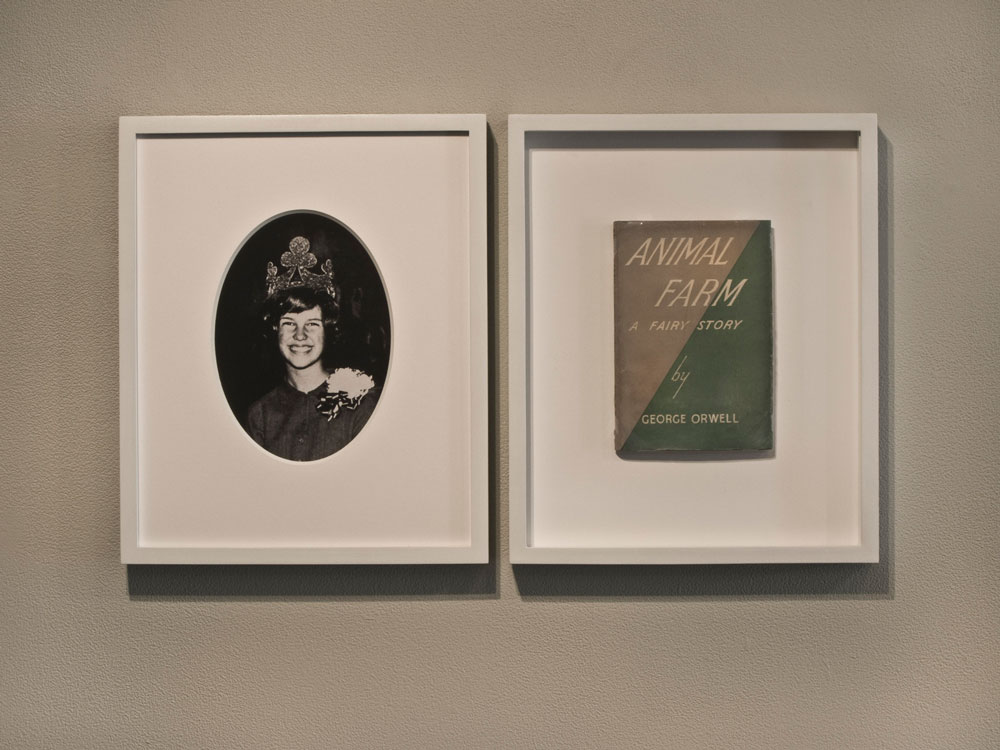

This bipedal turn, a progress from four legs to two, is carried forward in Princess (1964) (2015)—a first edition of George Orwell’s 1945 novel Animal Farm: A Fairy Story framed beside the enlarged yearbook photo of Manson Family member Leslie Van Houten at age 14 as homecoming princess.

Ydessa Hendeles, Princess (1964), 2015. Pigment print on archival paper and first edition copy of Animal Farm (1945) by George Orwell, both framed in hand-painted white poplar frames, 14 1/2 x 24 9/16 x 1 3/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Princess (1964), 2015. Pigment print on archival paper and first edition copy of Animal Farm (1945) by George Orwell, both framed in hand-painted white poplar frames, 14 1/2 x 24 9/16 x 1 3/8 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

“Chosen by the boys of their class to reign over Homecoming festivities, they enjoyed being known as Royalty for one week,” reads the original text in Van Houten’s yearbook. She is currently serving a life sentence for her role in the murders of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. Royalty one week, animal another—I can’t help reading this as an uneasy parallel to Trump crowning Alicia Machado Miss Universe one week and “Miss Piggy” the next.

Unlike the central figure in Sow, Van Houten fell victim to her predator as the 1960s utopian commune shattered. Hendeles’s notes suggest that Van Houten’s inability to “explain her transition from model teen to brutal killer” is the reason for her continued imprisonment. According to the courts, she is still more animal than human.

Orwell’s Animal Farm contrasts this particular trajectory of dehumanization when the pigs of the novel, once freed from captivity, reject any association with their human former masters. “Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy” initially defined their revolt. But as their utopia cracked and corrupted, it quickly became: “Four legs good, two legs better!” Together, the Van Houten photo and Animal Farm critique many factual and fictional utopian impulses.

Ydessa Hendeles, Three Little Pigs, 2015. Sound video housed in custom-made, wall-mounted 1/4-inch steel plate box with key-lock door and antique chain; cast-bronze sculpture on wall-mounted steel shelf installation, 22 3/8 x 35 x 4 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Three Little Pigs, 2015. Sound video housed in custom-made, wall-mounted 1/4-inch steel plate box with key-lock door and antique chain; cast-bronze sculpture on wall-mounted steel shelf installation, 22 3/8 x 35 x 4 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Tackling similar impulses concerning consumption and destruction is Three Little Pigs (2015), an installation containing an ominous locked metal box accompanied by a miniature sleeping (maybe dreaming) metallic pig. Turning the key to open the metal container reveals documentary footage of a “controlled-atmosphere killing” of three pigs—like a sinister episode of How It’s Made—mounted beside the gallery’s large kitchen. The video breaks into a kaleidoscope of cries and squeals, audible over an accompanying Jewish liturgical dirge reserved for mourning rites, as the three pigs struggle to escape a cage rapidly filling with carbon dioxide. The metal effigy—perhaps a full-body death mask—keeps dreaming amid the cries. After the viewing, the kitchen becomes much less appetizing.

These industrial killing protocols are constructed without acknowledgement of the many studies showing that pigs possess complex levels of intelligence, akin to those of dogs and primates. Pigs are emotionally and socially aware creatures. Yet, as Hendeles’s appropriation of the documentary video and accompanying text illustrate, they are rarely treated as such.

“Immigrants aren’t people, honey,” said one Trump supporter caught on video, and “Death to Pigs” contains many less than subtle hints at histories of dehumanization: the Germanic origins of The Story of the Three Little Pigs, the label “Made in Germany” emphasized on the back of the toy in Hope (2015), the inclusion of stories where farm animals represent historic dictators, and the torturous images of asphyxiating pigs concealed behind a locked metal door.

Ydessa Hendeles, Hope, 2015. Five pigment prints on archival paper, framed in hand-painted white poplar frames, 30 3/4 x 53 x 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Hope, 2015. Five pigment prints on archival paper, framed in hand-painted white poplar frames, 30 3/4 x 53 x 1 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

More concerning, these elements look out toward potential consequences of recent political events. One day after Trump was announced as president-elect, a spray-painted swastika appeared on a wall in New York with the words “Make America White Again.” In Ottawa, a red, almost blood-like swastika was painted on the entrance to a Jewish prayer centre. The symmetry—across times and national boundaries—is not lost on me.

Black Mirror‘s “We revel in cruelty…it’s a weakness that should be bred out of us,” is a contradictory call. Industrial killing machines remain in fact and fiction, whether in the form of a controlled carbon-dioxide chamber or a weaponized bee. The inescapable irony embedded in both #DeathTo and “Death to Pigs” is that in spite of ideas about the almost-utopian future/present, dystopian forces persist. It remains too easy for the outsider to become the other, losing their humanity in the process. The criteria for (in)humanity are more complex than walking on two legs.

The three bisque porcelain dolls in Family (2015), gradually morphing from human to pig—or pig to human, depending—stare blankly back at the exit of the gallery as if to ask: Are two legs really better than four? I am not so sure anymore.

Evan Pavka is the editorial intern at Canadian Art.

Ydessa Hendeles, Family, 2015. Pigment print on archival paper, framed in hand-painted white poplar frame. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Family, 2015. Pigment print on archival paper, framed in hand-painted white poplar frame. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Prize, 2015. Oil painting suspended from painted steel chains, anatomical model, child's table, 116 x 36 x 24 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Ydessa Hendeles, Prize, 2015. Oil painting suspended from painted steel chains, anatomical model, child's table, 116 x 36 x 24 inches. Courtesy the artist and Barbara Edwards Contemporary. Photo: Robert Keziere.