In his introduction to the “Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools” catalogue, co-curator Scott Watson writes, “This exhibition was occasioned by a gathering, the Dialogue on the History and Legacy of the Indian Residential Schools, held at the University of British Columbia First Nations House of Learning on November 1, 2011.” Among the gathering’s attendees was Chief Robert Joseph, who “asked those of us present if we could act to raise awareness of the history and legacy of residential schools.” From this request, Watson and co-curators Geoffrey Carr, Dana Claxton, Tarah Hogue, Shelly Rosenblum, Charlotte Townsend-Gault and Keith Wallace spent the following two years gathering commitments from elders, artists, scholars and curators to share artworks, words and images pertinent to a government program that sought not to “protect a class of people who are able to stand alone,” to quote former Indian Affairs deputy superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott on the introduction of his department’s Bill 14 amendment to the Indian Act in 1920, but to have them “absorbed into the body politic”—until there is “no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”

As many of us have learned over the course of this exhibition, Bill 14 (which included mandatory school attendance for “Indian children” between the ages of 7 and 15) resulted not in a gentle assimilation of Aboriginal people through an educational system, but a veritable horror show that further alienated those it sought to integrate—not only from their own culture, which was the implied goal, but from a modernizing settler culture that saw Aboriginal people as downstairs workers in what is today a country transitioning from a market state to a market society. Indeed, Scott’s desire to see Bill 14 assist in the elimination of a federal department that, for better or for worse, has concerned itself with the lives of Aboriginal people tells us that the “body politic,” like the market state, is itself a transitional node from which human relations will no longer be governed by politics, but be brokered by finance.

Which brings us to Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper’s June 11, 2008 statement of apology on behalf of Canadians for the Indian Residential Schools system. What does it mean to hear an apology from a head of state on behalf of a country when the actions of this man’s government have made it clear that he views this country less as a political or philosophical entity than as a transnational trading post? Moreover, if a head of state does not seem to care about the apparatus that has created a wrong (and necessitated its apology), are we wrong to question the sincerity of that apology? And if that apology is insincere, then what might we expect, or not expect, from it?

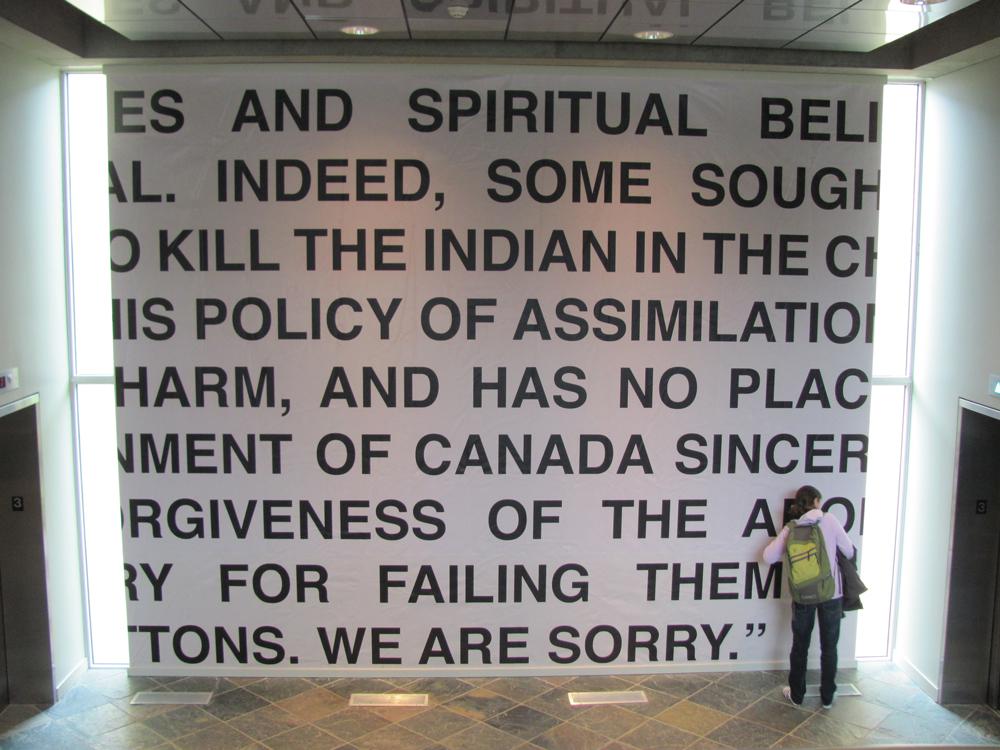

Among the 22 artists participating in “Witnesses,” it is Cathy Busby who has taken an excerpt from Harper’s apology, enlarged it and applied it to the exterior of buildings in Melbourne and Winnipeg. A piece of that text entitled WE ARE SORRY 2013 (2013) is now installed inside UBC’s Walter C. Koerner Library, where we are asked as witnesses to consider it once more. But as what? A text whose top and sides have been trimmed in an effort to fit it into this modernist building? A text whose resonance lies in its familiarity, and therefore its ability to regenerate what lies beyond those trimmed edges? I am not sure the occasion of this text is so familiar to us that we can complete it. Or if it is familiar, it is not its heartfelt content that comes to mind, but a rhetorical form that has more in common with the mechanical (and aesthetic) structure of the building than a road to truth and reconciliation.

Works that come closer to addressing the complexity of Aboriginal-settler relations are found within the Belkin Gallery proper. In Skeena Reece’s video Touch Me (2013), an Aboriginal woman, played by the artist, bathes a non-Aboriginal woman, played by artist Sandra Semchuk (who has also contributed work to the exhibition). However, as the video progresses we see from the actors’ expressions that their relationship is not simply one of economics, while at the same time being a relationship that does not preclude that form of exchange. A similar sensation arises in watching Lisa Jackson’s video Savage (2009), where the viewer is uncertain as to whether a grief-stricken woman (also played by Reece) whose daughter has been taken away is reacting as the mother of a child taken to a residential school, or, indeed, as a grown-up version of that child. (Perhaps, as in so many documented cases, the answer is both.)

Ambiguity of presence is also conveyed in Rebecca Belmore’s video Apparition (2013), where the artist kneels before the camera, her mouth taped shut. Although Belmore has said in the exhibition catalogue that this work “reflects my understanding of the loss of our language,” a loss brought on by “the deliberate role [residential schools] played in the silencing of our languages,” the gesture could also be read as a refusal to express that loss in the language of its exterminator. Not so with Gina Laing, a survivor of the Alberni Indian Residential School who, during the exhibition opening, sat beside a series of works on paper she made in the mid-1990s. For Laing, availing herself to those who want to know more about her haunting paintings and their accompanying texts was both an educational endeavour and part of the same therapeutic project that gave rise to these works. (In thinking of these works now, I am reminded of the paintings of Charlotte Salomon, whose own series Life, or Theatre?: A Song Play (1941–43), survived her silencing at the hands of Nazi jailers.)

Other notable works include Gerry Ambers’s Dzunukwa Dreaming of Summer Holidays (1992), a large acrylic painting that owes something to the whispering intensity of Edvard Munch while anticipating the dreamier paintings of Peter Doig and Daniel Richter. Set inside a residential school ward, Ambers’s canvas depicts an abstracted, silhouetted figure stretched out on a bed (one of the first works encountered in “Witnesses” is a serial silhouette print work by Faye HeavyShield) and a slightly more realized subject moving towards a coffin-shaped space made by the parting of window drapes. Both figures are dreamers, though each one could represent the dream of the other, with a third figure, half-hidden by a pillar, providing the means by which that relationship is enacted. Nearby is Adrian Stimson’s Sick and Tired (2004), which features a bed whose mattress has been removed, and behind it three window frames from a residential school that have been “stuffed” with feathers. Atop the bed is a bound presence evocative of the silhouetted figure in Ambers’s painting.

To say that Ambers’s painting and Stimson’s installation play well together reminds us how shared experiences generate within us a sympathetic system independent of the mediums that carry such works. It is also a testament to the role curators play in generating events both inside of and outside of the gallery space. An example of this can be found in the increasing importance of public programming, particularly where an assumed knowledge of modern art history, with its emphasis on formal innovation, is inadequate when faced with political-economic rationalizations that result in the internment and destruction of those identified by gender, race, ethnicity and class.

Held in the last weeks of the exhibition, the accompanying symposium Traumatic Histories, Artistic Practices and Working from the Margins offered a number of panels and presentations by elders, artists, scholars and curators that spoke equally of the work in the exhibition and the issues that gathered that work together. Elder Larry Grant began by reminding us that we were on unceded Musqueam territory, and also of his hybridity (he is of Chinese and Aboriginal descent), reflecting on how that status provides its own unique lens. Richard Hill followed with a formal analysis of the paintings of Norval Morrisseau; then came Ryan Rice, who told us about the colour red and the multi-media work of Carl Beam. In what was perhaps the symposium’s most fruitful session, scholar Charlotte Townsend-Gault—who appeared on a panel with David Garneau and Steven Loft—focused on the work of artists Rebecca Belmore, Dana Claxton, Beau Dick and Neil Eustache, at one point reminding us of Jimmie Durham’s oft-noted observation that the problem of colonialism lies not with indigenous people but with the concept of nation. This observation was echoed by Garneau and Loft when speaking of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a process geared not at those who survived the residential school system, but those eager to “assuage” themselves of its consequences.

Now in its closing days, “Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools” is already the best-attended exhibition ever mounted at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, a gallery that opened with paintings by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun and has, over its 18 years, given us important shows by Rebecca Belmore and Ki-Ke-In (Ron Hamilton). However, it was not the work of “Witnesses” artists and curators, nor of government policymakers, that came to mind when leaving the symposium for one last look at the exhibition, but a public art commission by Luis Camnitzer that the Belkin erected atop its building in 2011. For it is here, in language opposite that of the deliberately impenetrable Indian Act, that we are reminded how “THE MUSEUM/IS A SCHOOL:/THE ARTIST LEARNS/TO COMMUNICATE,/THE PUBLIC LEARNS/TO MAKE CONNECTIONS.”