As Winnipeg tilts toward the annual false start of spring, artworks and exhibitions around here seem to be showing the lingering effects of the season. Though it’s cliché to mention the extreme weather in our sun-chilled city, the very real early darkness and isolating cold remain catalysts for seasonal-affective activities such as mental time travel. While this can be a worrying trend to apply to creative practice, as artwork concerning memory can often be heavy on nostalgia and light on conceptual rigour, Winnipeg artists are creating sensitive, complex and exciting work on this subject that can spark life into a dim winter brain.

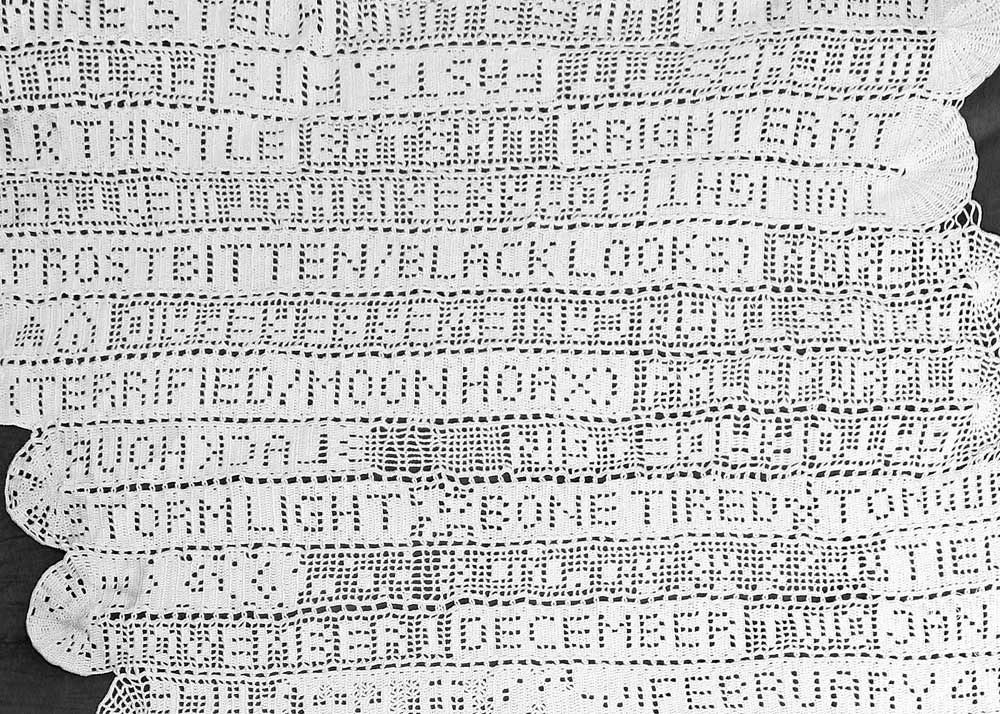

When I visited Steven Leyden Cochrane’s studio earlier in the season, his banner-cum-blanket of crocheted text already took up most of the dining table. Beginning with a memory of a train of thought, the artist has been transcribing a sequence in yarn. Sometimes working without a pattern, Cochrane here and there has put in bits of static to indicate missing memory, using a coin toss simulator to decide which dots will be empty and which will be filled; elsewhere, he has run bits of text through a software version of Conway’s Game of Life. Every fired synapse and pixel has been translated into the physical realm with the looping and spinning of yarn.

As a line in Cochrane’s banner/blanket flows onward, it turns a corner and is joined to the previous line, the path collecting in a way that resembles of the folds of a human brain. Throughout the winter, this winding mesh tract has multiplied before the eyes of @svlc_’s Instagram followers, who have been able to witness the process, feeling every moment of the feverish coziness of this faulty quilt, whose holes render it ineffective at physical comfort.

Divya Mehra’s neon sign at the Tallest Poppy in Winnipeg—like the sandwich she has added to the restaurant’s menu—evokes her parents’ experience running a Jewish-style deli, among other events. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Divya Mehra’s neon sign at the Tallest Poppy in Winnipeg—like the sandwich she has added to the restaurant’s menu—evokes her parents’ experience running a Jewish-style deli, among other events. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

George Steiner’s reflection that “it is not the literal past that rules us…. It is images of the past” is brought to light by the work Divya Mehra created during her January residency (facilitated by Synonym Art Consultation) at the Tallest Poppy restaurant. The artwork was inspired by her family’s experiences emigrating to Winnipeg, including the creation of a drawing of an impossible sandwich by the artist’s father, Kamal, for the first menu of Mehra’s Deli, which Kamal and Mehra’s mother, Sudha, opened in the mid-1970s.

In Winnipeg, Kamal first worked in a restaurant called Deli Deli, where he gained experience making sandwiches. When he and Sudha opened a restaurant of their own, they didn’t start with Indian food because, in that time and place, as Mehra said, “no one would eat it.” Instead, having seen Deli Deli’s success, the two South Asian newcomers started a traditional Jewish-style delicatessen. Initially sticking with classics like a Reuben with fries, coleslaw and a dill pickle, they began sneaking Indian food onto the menu.

Some 30 years later, working with Talia Syrie, chef and owner of the Tallest Poppy (itself a contemporary take on a Jewish diner), Mehra performed the experience of her parents, offering an interpretation of an interpretation of a traditional Jewish sandwich. Mingling the original menu with childhood memory, Mehra created a deli sandwich with five inches of stacked meat and several slices of cheese on bread, complete with a flag created by the artist bearing the “Mehra’s” logo, to be served at the restaurant until summertime at its original price of $6.95.

When Mehra’s mother learned of the sandwich’s creation, a chasm between memory and reality was revealed. As Mehra paraphrased for me via text message, her mother’s reaction was along the lines of “IT’S FIVE OUNCES OF MEAT, NOT FIVE INCHES! WHY ISN’T THE CHEESE MELTED? WHY ISN’T THE MEAT ROLLED? I THOUGHT TALIA WAS JEWISH?” On day two of the residency, Sudha showed up at the restaurant and schooled Syrie and Mehra on how to make the Mehra’s Special.

In conversation with Synonym Art Consultation about the project, Mehra’s spoken notes were misinterpreted and, instead of relaying that Kamal worked at Deli Deli, the press release stated that he was from Deli Delhi, India, a nonexistent place. In response, Mehra created a tongue-in-cheek neon sign for the front window of the Tallest Poppy called New age Delhi, under old management and the East India Company. The neon sculpture glows with an image of the sandwich surrounded by the words “DELI DELHI CLUB,” the letter H flashing off and on, flickering between layers of public and personal, expectation and interpretation, performance and identity.

The collective CONSTELACIONES (with Roewan Crowe, Doris Difarnecio, Christina Hajjar, Monica Mercedes Martinez and Helene Vosters) helped bring a member’s ceramic sculptures to the Chilean desert in the performance Return Atacama (2016). Photo: Cassie Scott via MAWA Facebook page.

The collective CONSTELACIONES (with Roewan Crowe, Doris Difarnecio, Christina Hajjar, Monica Mercedes Martinez and Helene Vosters) helped bring a member’s ceramic sculptures to the Chilean desert in the performance Return Atacama (2016). Photo: Cassie Scott via MAWA Facebook page.

At the Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art annual Caroline Dukes Memorial Artist Talk on March 3, the collective CONSTELACIONES, dedicated to process-based, trans-hemispheric collaboration, gave a talk about their work as a multidisciplinary group.

In a recent performance titled Return Atacama, the group carefully wrapped and then carried Chilean-born, Edmonton-based member Monica Mercedes Martinez’s heavy, cross-shaped, ceramic forms from Winnipeg to Chile’s Atacama Desert. They worked together in order to create community and solidarity around Martinez’s return to the land that her family fled in 1974 due to Chile’s military coup, migrating as a group to the landscape she has struggled to connect with her entire life.

As they stood before the crowd at MAWA describing their work, the members of CONSTELACIONES shouldered the heavy weight of ceramic shards they had returned to Winnipeg piled inside a blanket. They also invited audience members to relieve them of this burden, passing along their share of the weight as each member moved to the front of the room to speak about their contribution to and experience of Return Atacama.

Martinez described placing her artwork in the Chilean desert—a site of trauma—working in the punishing desert elements, unwrapping and then carrying the forms to the gathered witnesses, and laying them before the witnesses’ feet, over and over again. The labour of transporting these materials was, as CONSTELACIONES described, a process of release, allowing the forms to return to sand. Following the talk, members of the audience were invited to take home pieces of the sculptures that were carried on the collective’s shoulders, lightening the artists’ loads and opening the possibility for new ritual and engagement with these fragments of memory.

Dana Kletke’s yarn sculpture, which refers to the blood clots impacting her mother’s brain structure and function, is part of “Neurocraft” at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre.

Dana Kletke’s yarn sculpture, which refers to the blood clots impacting her mother’s brain structure and function, is part of “Neurocraft” at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre.

Delving into the depths of memory from a scientific perspective, “Neurocraft,” a collaboration between the Manitoba Neuroscience Network and the Manitoba Craft Council, pairs artists with neuroscientists to help present research around the brain to the general public. Nine artists were given access to hospital settings and doctors in order to develop a project that spoke to their interests.

The exhibition of the final artworks runs until March 31 at the Health Sciences Centre’s John Buhler Research Centre. Video, yarn, ceramic, light, printmaking and drawing are among the many media used to create this tactile and engaging show.

Dana Kletke’s works make the personal universal, speaking to experiences with her mother’s stroke and the ongoing fear, difficulty and acute awareness of personality change that accompany recovery from a brain bleed. On one side of a small false wall, Kletke’s two diminutive and detailed pencil drawings refuse to give up an answer as to what they depict.

Nose almost touching the glass, frustrated, I finally turn to the exhibition catalogue for guidance, feeling acutely the effectiveness of the artworks in illustrating their point. The answer flushed my brain with relief—understanding—but also a germ of worry. The tiny, pedantic drawings are of washcloths, a seemingly innocuous symbol of the domestic dailiness of Kletke’s mother’s precise life and habits. The washcloths are rendered slightly askew, revealing the depth of a stroke’s damage and the loss of the kind of memory that involves our very way of being.

On the other side of the wall, a stunning red sculpture is comprised of hundreds of single, lengthy threads of yarn, which are held at the top with long pins and cascade down almost to the ground, collecting near the bottom. A quarter of the way down the strings, Kletke has teased each length of yarn into its own large, fuzzy clump. The tactile loveliness of the sculpture is held in tension with its troubling meaning: as Kletke writes, “blood clots reflect the daily ritual of thinning the blood and the ever present damage…how memories are lost and how some memories can be recovered in time.”

As with the washcloths, the artist’s careful, repeated actions bring to mind the kind of repetition it takes to create (and re-create) muscle memory. These actions also recall the double-edged nature of remembering itself, which is always tricky, giving and slipping from grasp.

Letch Kinloch is an arts administrator and founder of Also As Well Too Artist Book Library in Winnipeg.