Neither a broad-based overview nor a wrapped-up retrospective, the recently closed “Winnipeg Now” was a sharp-focus look at 13 artists with creative roots in this mid-continental city. Curated by Border Crossings’ Meeka Walsh and Robert Enright as part of the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s centenary programming, this exhibit featured big, ambitious site-specific installations.

In a town that can experience life-threatening cold, it came as no surprise that several works explored the borders between culture and nature. In Sarah Anne Johnson’s multimedia construction Untitled (Schooner and Fireworks), stumpy Sculpey figurines drink and fight on an Arctic-bound ship underneath a canopy of fireworks made from vacuum-moulded plastic. Johnson subverts the Lawren Harris–inflected ideal of the pristine polar landscape with messy exuberance.

The title of Rodney LaTourelle’s Winnipeg Supply references a now-defunct hardware store. Vaguely functional-looking, the large-scale wood-and-metal construction is transformed by LaTourelle’s immaculate colour sense, its pale, pearlescent hues suggesting the muffled light of a snowbound landscape.

KC Adams‘s forest of fragile porcelain trees titled Birch Bark Ltd. was created by riffing on the traditional indigenous technique of birchbark biting to etch familiar corporate logos into each tree’s trunk. (Significantly, at least for me, the piece was positioned across from the show’s sponsor wall.) Jennifer Stillwell’s works in poured paint and epoxy resin settle into topographical runnels to suggest a vast winter panorama. A closer look, however, reveals that the ridges are formed by multicoloured baking sprinkles, and the scale suddenly flips to the cozy and domestic.

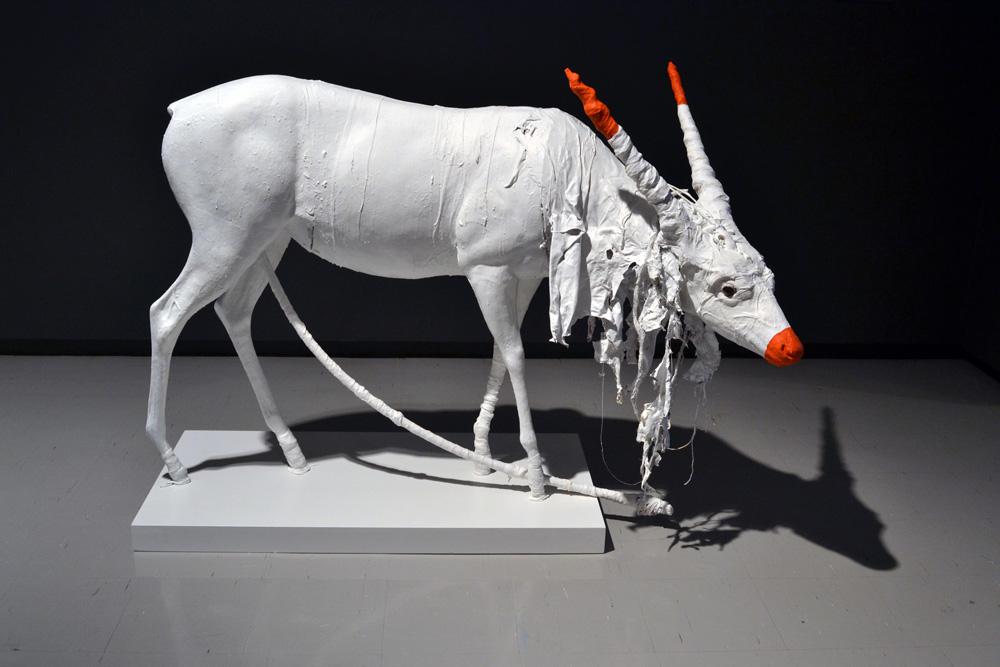

Surrounded by the temporal layers of a slow-growth city, Winnipeg artists often look to the past or conjure up elaborate personal mythologies. Self-declared “artist witchdoctor” Michael Dudeck’s queer cosmology was represented in “Winnipeg Now” by some of his startling hybrid beasts. Marcel Dzama’s multimedia works for the show mine art history with a black-and-white chess ballet that references Duchamp, Dada and expressionist film.

A figurative piece by Kent Monkman, an artist of Cree ancestry, fuses the forcible relocation of the artist’s great-grandmother from the shores of the Red River with the biblical story of Lot’s wife. In it, a two-spirited berdache figure is punished for the sin of looking back, but through her punishment—frozen in melancholy glamour and white chiffon in the middle of the grasslands—she becomes a moving symbol of remembrance.

Filmmaker Guy Maddin is closely connected to the city’s visual arts community, his work lately veering toward intimate cinematic installations or huge, Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerks. Only Dream Things calls up the sudden death of his older brother, Cameron, when Guy was a young boy, a trauma compounded by the fact that he immediately inherited Cameron’s eternally adolescent bedroom. While obsessively literal in its detail—the stacks of National Geographic issues, the blond pine furniture—the room also functions as a film set haunted by (as Maddin has put it) “myths, perfervid myths!” Exhibited along with layers of projected footage, it stands as both the genesis and generator of Maddin’s dreamy, inward-looking oeuvre.

Paul Butler’s latest work takes on the North American myth of self-improvement, using photo-collage to deftly tweak the shiny surfaces and preternaturally peppy tones of aspirational advertising. In a Winnipeggish bit of self-deprecation, Butler implicates himself in what he’s satirizing, with a video that scans through years of his scrawled personal notebooks and Oprah-esque to-do lists, resolutions and goals.

Several artists express a locally prevalent love for outdated technologies. Daniel Barrow’s distinctive drawing style, in which ripe beauty is always about to tip over into rot, is conveyed through lo-fi mechanics that seem both jury-rigged and incredibly ingenious. His bank of overhead projectors in this show had as much aesthetic weight as his projected imagery.

Bedtime Stories for the Edge of the World, by Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan, can be experienced as an exquisite bookwork/multiple; in this show, one of the stories could also be listened to on an old-timey phonograph that slowly unreeled the precision of Dempsey’s confidential, chummy voice. The stories are cheeky comic tales of pirate queens and radical inventrixes, but it’s the medium that matters too: The phonograph edition seemed politely insist that the listener actually sit still.

Dominique Rey’s works shown in “Winnipeg Now” also explore slowness. The installation Greenhouse meticulously replicates a local nuns’ greenhouse right down to banal details like a half-full watering can. Her video Les Filles de la Croix further explores communities of elderly nuns, the unhurried footage embodying a radically different experience of time.

In the last decade, Winnipeg’s artists have pulled off some high-profile successes, but taken together, these works reflect an art scene still characterized by stubborn particularities and unexpected idiosyncrasies. “Winnipeg Now” couldn’t be be neatly summed up—which is hard for art reviewers, but probably good for art.