How do you define “downtown” in post-industrial cities like Windsor, Hamilton and Detroit? What is the nature of the downtown in cities where factories closed years ago? These cities offer opportunities for emerging artists who can’t afford Toronto—Ontario’s cultural hub. In “Downtown/s – Urban Renewals Today for Tomorrow: The 2017 Windsor-Essex Triennial of Contemporary Art,” 22 artists living and working in Southwestern Ontario explore the changing cultural landscape of post-industrial urbanism.

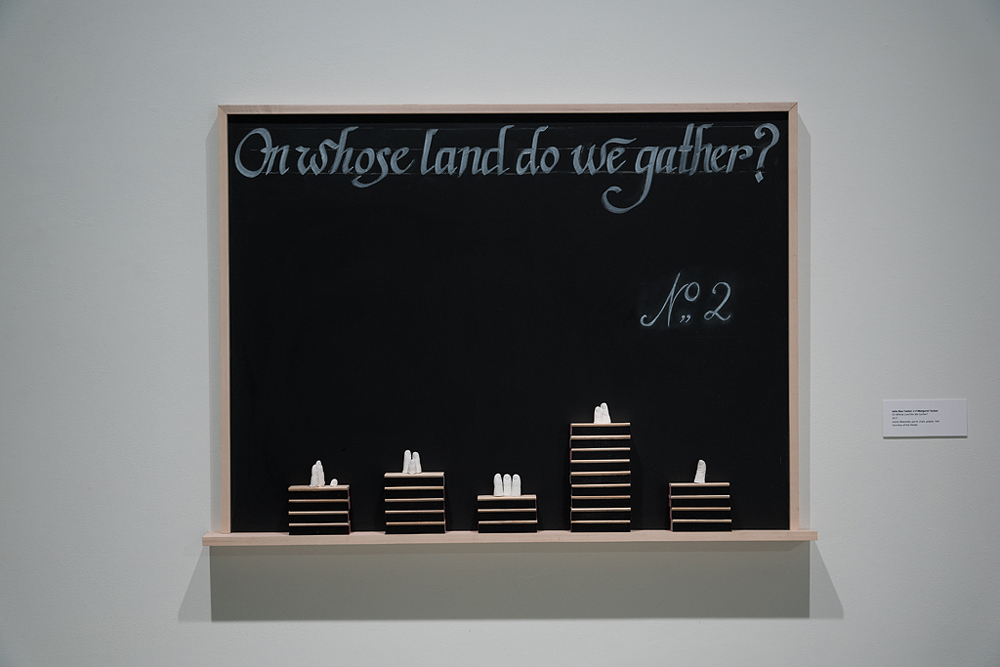

The first work I encountered upon entering the exhibition at the Art Gallery of Windsor was a collaboration by Julie Rae Tucker and her mother, Margaret Tucker, On Whose Land Do We Gather? (2017). Informed by Margaret’s experience in the residential school system, this chalkboard installation provides an important framework for an exhibition so rooted in place.

Inherent to ideas of place are our memories of them and the stories we tell. A performative work, Stories of Windsor: Reimagining places of fascination (2017) by Terry Sefton and Kathryn Ricketts, explores the primacy of place in memory through improvised music and dance. Spectators are asked to contribute short stories specific to a place, to be performed by the artists over the course of the exhibition.

Julie-Ray Tucker and Margaret Tucker, On Whose Land Do We Gather?, 2017. Wood, Masonite, paint, chalk, plaster, felt. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Julie-Ray Tucker and Margaret Tucker, On Whose Land Do We Gather?, 2017. Wood, Masonite, paint, chalk, plaster, felt. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

In contrast, Jessica Frelinghuysen’s work, Jessercise ArtFit Exercise Circuit (2015–2017) invites viewers to perform. Located around the gallery, in the museum elevators and along Windsor’s waterfront trail, her ArtFit plaques provide simple diagrams with easy to follow instructions.

“Neck Stretches” demonstrates how to stretch your neck while “contemplating art.” “Book Bag Rows” assure you that grunting helps with this workout that allows you to maintain your art-nerd status. “Ren-Cen Stand,” located in the sculpture garden of the AGW facing Detroit’s skyline, encourages you to perform a handstand, making yourself “tall and straight like that glass building across the river.”

This direct reference to the Renaissance Centre playfully criticizes Detroit’s 1970s attempt at revitalization via corporate displays of wealth. Conjuring the inevitable failure of sustaining a tall and straight handstand, Frelinghuysen reframes a seven-building skyscraper complex by General Motors as a monument to failed industry and a reminder of unemployment brought on by our post-industrial age.

Jessica Frelinghuysen, Jessercise ArtFit Exercise Circuit, 2017. Images printed on Dibond. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Jessica Frelinghuysen, Jessercise ArtFit Exercise Circuit, 2017. Images printed on Dibond. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Frelinghuysen is not the only one looking across the river.

Jessica Thompson’s vinyl text, Should we stay or should we go? (2017) literally points at Detroit through its installation on the gallery’s glass façade. Evoking a typeface from the 1850s which would later become known as “Jim Crow” and was used in advertisements by slave owners, Thompson imbues this seemingly simple and subtle work with historical baggage.

Thompson explained to me that the titular question reflects her family’s struggle as African Americans with migration and settlement after the Great Migration, as well as a renewed urgency around it with the election of the Trump administration.

Thompson’s family migrated from the southern United States, settling in Detroit and in Ontario. Her immediate family, who chose Ontario, grappled with the decision to leave the US—“Should we go?”—and now, the current political climate has her family in Detroit wondering, “Should we stay?” At a time when civil rights, racism and migration are back in the American political arena, it is important to revisit these histories.

Jessica Thompson, Should we stay or should we go?, 2017. Vinyl. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Jessica Thompson, Should we stay or should we go?, 2017. Vinyl. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Back inside the museum, I encountered another installation on the theme of migration in a work that refers to Windsor’s industrial economy in a most beautiful way.

Soheila K. Esfahani’s Cultured Pallets: Windsor (2017) uses a William Morris–inspired floral print to explore ornamentation as a form of “portable culture.” The ornamented shipping pallets thus combine understandings of portability and globalization. The items we bring with us when we migrate to a new place and the portability of the goods manufactured in our cities become part of the global economy.

These locally sourced shipping pallets will return to circulation after the exhibition closes.

Soheila K. Esfahani, Cultured Pallets: Windsor, 2017. Acrylic on wooden shipping pallets. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Soheila K. Esfahani, Cultured Pallets: Windsor, 2017. Acrylic on wooden shipping pallets. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Stress (2016) by furniture-makers Carey Jernigan and Julia Campbell-Such explores changing rhythms of work and industry in its resuscitation of hand-crafted ways of making.

Patterned after a wooden gear, carefully carved by the artists, are three cast cogs mounted on the wall, two aluminum and one bronze. William Morris rears his head again in this reference to the tension of the late 19th century Arts and Crafts movement’s reaction against an industrializing society. The rhythms of work are upset as the motion sensors linked to the cogs are triggered by my approach, spinning the cogs faster and faster.

The technology that moves these industrial objects belies their careful construction as art objects and emphasizes this tension between the history of industry and the resuscitation of hand-crafted works in our post-industrial age.

Carey Jernigan and Julia Campell-Such, Stress (on wall) and Play (on floor), 2016. Wood, nylon, cast aluminum, cast bronze, motion sensor, Arduino microcontroller, DC motor. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Carey Jernigan and Julia Campell-Such, Stress (on wall) and Play (on floor), 2016. Wood, nylon, cast aluminum, cast bronze, motion sensor, Arduino microcontroller, DC motor. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

I’m drawn to subjective mapping projects, and the one in this triennial is made more interesting by my complete lack of familiarity with Windsor’s downtown outside of my experiences with border-crossing.

A collaborative project between the In/Terminus Creative Research Collective (Michael Darroch and Lee Rodney) and the Hamilton Perambulatory Unit (Donna Akrey and Taien Ng-Chan), KM2: Reconaissance, Heart + Soul (2017) takes the theme of the downtown core and maps the things that both make up and break up the “heart” of a city. The collective believes that these things have an emotional weight that is woven into the historical and cultural fabrics of downtowns.

This participatory project began at noon the day of the triennial’s opening with a “strata walk.” Participants were led from the Windsor Armouries, the newly repurposed location of the University of Windsor’s School of Creative Arts, on a collaborative mapping project of the city that explored the relationships between Windsor’s military history as a border town, shifting practices of security, and the subjective ways in which we define our downtowns.

Individual maps of different neighbourhoods were marked by participants, with various symbols representing things like security cameras and guards, art and human interventions, and marks of capitalism and gentrification. These were then compiled into a single large map, pocked with red icons indicating of the composition of Windsor’s downtown. Like any good subjective mapping project, KM2 put bodies in the streets of Windsor, moving and feeling their way through the core, coming to individual and collective understandings of what makes this city’s heart beat.

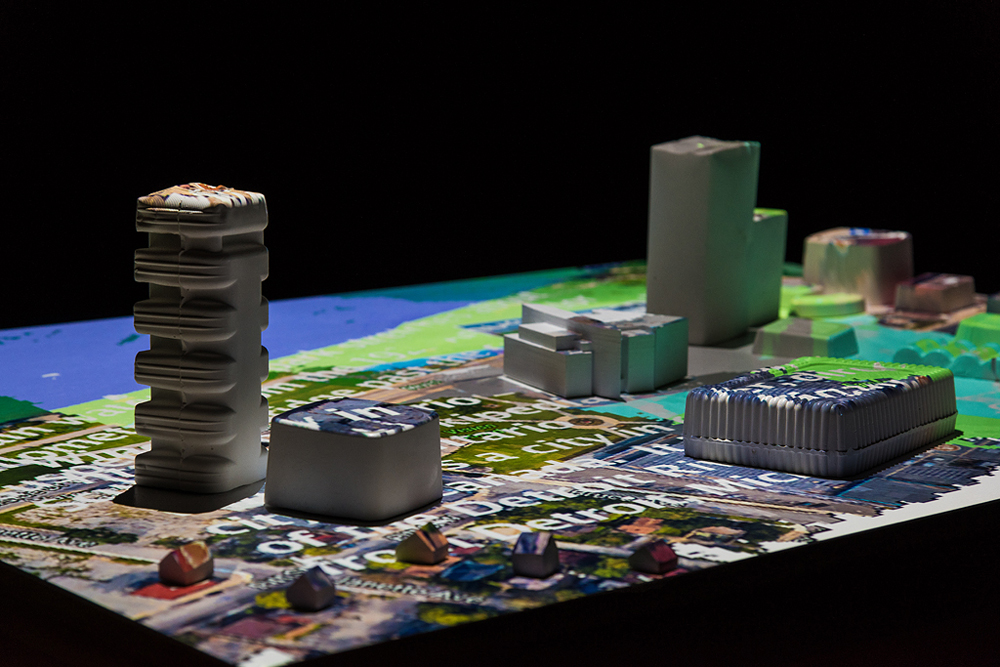

Taien Ng-Chan, Stratigraphic City, 2017. Plaster, wood, 3D-printed plastic, paint, various media. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Taien Ng-Chan, Stratigraphic City, 2017. Plaster, wood, 3D-printed plastic, paint, various media. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

“Downtown/s – Urban Renewals Today for Tomorrow” is an exhibition is about how place is embodied, how we move through and experience our downtowns and how we define and are defined by them. It is about the role of history in these definitions and our attempts at grasping that history to make sense of our future cities.

The choice of location and installation of its artworks creates an effective dialogue with the city of Windsor. As the artists included in the triennial form understandings of their different downtowns, we as spectators reflect upon our own.

Curator Jaclyn Meloche, a relative newcomer to the city, has made her passion for her new downtown abundantly clear through her organization of this exhibition. She has brought enthusiasm and a sense of excitement to a city many have not felt excited about for a while now. “Downtown/s – Urban Renewals Today for Tomorrow” gets viewers eager for the renaissance Meloche and others might see coming in Windsor’s near future.

“Downtown/s – Urban Renewals Today for Tomorrow” continues at the Art Gallery of Windsor until January 28, 2018.

This article was corrected on November 28, 2018. The original copy misspelled Terry Sefton’s name.