There are moments when the stars collide and ideal artistic partnerships are forged—sometimes across the centuries, and spanning different creative media. Such was the case in 2010, when the revolutionary 1928 Vladimir Shostakovich opera The Nose was brought to new life at New York’s Metropolitan Opera thanks to the ingenious set designs of South African artist William Kentridge. Based on an 1836 short story by Russian master Nikolai Gogol, Shostakovich’s opera was written as a thinly veiled, comic attack on Soviet bureaucracy and thuggery, and Kentridge was just the man to update their political dialogue. Like David Hockney’s incandescent set designs for The Rake’s Progress and The Magic Flute at the Glyndebourne Festival in the 1970s, this production was a marriage of true minds, a kind of cross-cultural and trans-historical three-way between creative soulmates whose imaginations, together, engendered something rare and wonderful.

If you missed the Kentridge production in New York, though, you needn’t despair. This month at Barbara Edwards Gallery in Toronto, you can get a taste of it in 30 prints he made while working on his staging, works that reflect the artist’s intrigue with Gogol’s absurd narrative, and with the modernist musical masterpiece that Gogol inspired. A Russian bureaucrat of absurd pomposity, Gogol’s Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov awakens to find that his nose is missing. To his consternation, it appears that his nose is gadding about town, upstaging him in rank and making mischief, while the sudden and mysterious facial deformity threatens Kovalyov’s precarious grasp on societal privilege. He attempts to place an advertisement in the local newspaper for his missing body part, only to be rebuffed. He accuses his prospective mother-in-law of witchcraft for the abduction of his nose, threatening his own carefully crafted social ascent. At the conclusion, though, both his peace and his nose are restored, and all is well.

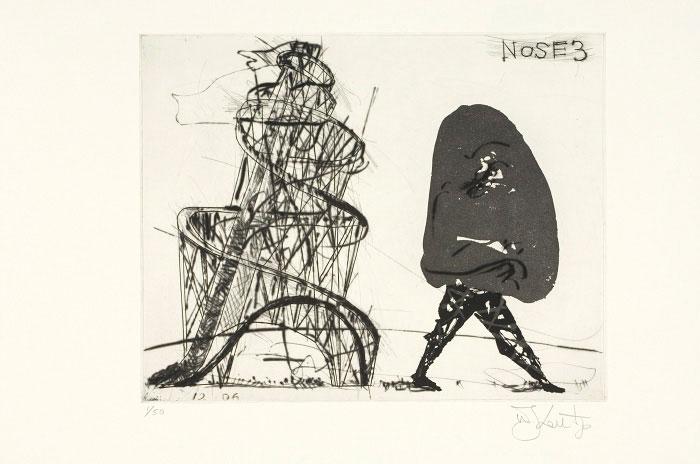

Looking at Kentridge’s suite of prints, one senses his inner ruminations on the nose as a symbol, and his creative fellowship with both Gogol and Shostakovich before him. A fleshy protuberance of inordinate sensual sensitivity, the nose is an obvious stand-in for the male member; could this be a tale about castration anxiety? (One of the prints has a nose poised to burrow between the legs of a reclining odalisque, a swollen paragon of voracious olfaction.) The nose, too, is seen by some as an ungainly body part, a source of potential embarrassment—is it too big, too small, too unkempt? Is it runny or pimply?—a humble and all-too-conspicuous body part around which strong feelings of shame and self-doubt can accrue. In several of these prints, Kentridge’s nose (and, indeed, this nose would seem to be a sort of self-portrait) seems to emanate an Eeyore-like, melancholy disposition, lumpy and alone. Like the boots and soles in the paintings of American artist Philip Guston, it conjures a common humanity (though Kentridge has also likened its form to Guston’s hooded Klansmen heads).

In other moments, though, the nose assumes a jaunty air, and art history is its playground. Kentridge pictures the pudgy proboscis chatting up one of Manet’s salopes at the bar, crowning a heroic statuary bust and a Picasso nude, and standing in as coy voyeur to one of Degas’s nude bathers, ever the connoisseur. Blithely transgressing gender—the nose appears astride a steed as an equestrian soldier (an homage to Cervantes, another kindred absurdist) and as a ballerina à la Anna Pavlova—the nose is everyman and everywoman, a kind of free-floating signifier capable of absorbing all the multiple readings one can ascribe to it and reconciling them in a symbol more complex than language alone could allow.

In many of these prints, as in the operatic staging, Kentridge borrows the visual vernacular of the Russian Revolution, applying Constructivist geometries to his scenes (in one, the nose ambles past the tilting form of Tatlin’s Tower), evoking the utopian aspirations of Communism in its glory days, before the descending horrors of the Great Purge. Kentridge makes of that history a humanistic cautionary tale, offering a critique of the kind of political structures and rigidly held beliefs that separate us from our fellow man, and from our own humanity. The son of South African civil-rights lawyers, Kentridge grew up under apartheid, exposed from childhood to its twisted logic of difference, sensitized to its madness. In his staging of The Nose, and in the further iterations of his thinking to which these prints attest, he mines those veins of reason and unreason with dark humour, sharp insight and—most winningly—dazzling creativity. These are classics of our time, and for all times.

William Kentridge’s Nose series (published by David Krut Print Workshop, Johannesburg) will remain on view at Barbara Edwards Contemporary in Toronto until June 28. The suite will be shown again at Edwards’s Calgary gallery from September 12 to October 25.