Could Canada ever produce an exhibition like the Whitney Biennial? Would we even want to? A national survey of contemporary art comprised primarily of newly commissioned work is no small task, and the Whitney Biennial has, inevitably, been a lightning rod for controversy in past years. It has been too busy, too white, too disparate, not disparate enough.

But this time around, the whole event left me feeling a little envious. It was the first iteration in the Renzo Piano–designed building, and the (relatively emerging) curators, Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, have walked a careful balance. It’s a show that feels urgent without making large pronouncements. There’s a sense of intimacy, even though you’re looking at the work of 63 artists and collectives. And even though the scope is national, many of the works are rooted in a specific sense of place.

Of course, this doesn’t mean the showing is free of flaws. There are plenty of disappointments, and I’m sure many visitors will leave feeling unmoored by the open-ended approach. But it feels like a show worth having, which is saying something.

If Canadians were to imagine a national biennial (or reimagine a national biennial, given that the National Gallery of Canada’s Canadian Biennial focuses solely on the gallery’s recent acquisitions), what could be gleaned from the strengths of this year’s Whitney Biennial, and how could they be distilled in another format? Here are five lessons based on the strengths of this year’s show.

1. Make it Intergenerational

The Whitney Biennial is often touted as a stage for exciting, young artists, which offers yet another reminder that the art world is about as youth-obsessed as Hollywood. Just switch out your rising star for an emerging artist and call it a day.

But make no mistake: the Whitney Biennial belongs to octogenarian women. Which is not to say that they’re the primary focus, far from it, but perhaps they should be. At the last biennial it was the then-89-year-old Etel Adnan; this year, it’s 87-year-old Jo Baer. Baer’s large paintings, pulled from her In the Land of Giants series, which she began in 2009, are spacey with just the right hint of New Age. The paintings come from her research into the prehistoric megalith of Hurlstone in Ireland, plenty of which was done on the Internet: there are large, flattened spaces of grey, megalithic rocks spouting fire and moody horizon lines. Baer is best known as a Minimalist, but her Whitney showing proves that all artists deserve a second life.

But it’s not just about giving Baer or Adnan their fair dues—it’s also the intergenerational exchange that happens when you put these works in proximity to others. An-My Lê is a generation or two younger than Baer, but the open spaces and flat planes of her meditative inkjet prints of Louisiana take on a different air when placed adjacent to the work of Baer. Lê’s work beautifully captures sugar-cane fields and buildings for lease (with scrawled graffiti that reads, “FUCK THIS RACIST ASSHOLE PRESIDENT”), but it’s her 2015 piece Film Set (“Free State of Jones”), Battle of Corinth, Bush, Louisiana that truly struck me. It’s almost like a history painting, but rather than conveying a myth, it’s a deft summation of myth-making itself.

Perhaps it’s the influence of art prizes and awards in Canada, where delineations of age are either explicit rules or unspoken criteria. The National Gallery of Canada’s biennial (slated to open its next edition in October 2017) has, in past outings, brought together a wide age range of artists—but not strictly contemporary work—and the retrospective collecting aspect has given it a decisively different feel. How often do we get a chance to see new work by artists of all ages brought together, outside of a specific thematic focus? Not nearly enough.

2. Indulge Site-Specificity

It’s little surprise that the Whitney indulged heavily in site-specificity in this iteration—it is, after all, its first biennial since the move downtown. Regardless of motive, the results are stunning.

Los Angeles artist Samara Golden has taken over the gallery’s west-facing windows, installing mirrors on the ceiling and floor of a little niche; miniature environments are built there, reflecting and refracting in the infinity room at every angle. Look one way and you see a penthouse apartment. In another direction, a cluttered office is revealed. Turn slightly again to find an abandoned institutional home of sorts, with feces-stained toilets and empty mechanized wheelchairs. It is entirely engrossing and confounding, and deeply unsettling.

Some of the other site-specific pieces are already Instagram hits. A more traditional, but still effective, approach to site-specificity is taken by Larry Bell, whose laminated-glass cubes catch the sunlight on the fifth-floor terrace. Raúl De Nieves has created 18 floor-to-ceiling windows with intricate panels that look like stained glass, but are carefully taped acetate sheets; a perfect backdrop for his beaded sculptures. The Occupy Museums installation, which embeds financial charts and work by a group of artists quite literally in a wall, offers a sobering take on artist debt—and the complicity that the boardrooms of galleries have with the austerity measures that are affecting the arts and artists.

Anicka Yi, still from The Flavor Genome, 2016. 3D high-definition video, color, sound; 22 min. Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist and 47 Canal, New York.

Anicka Yi, still from The Flavor Genome, 2016. 3D high-definition video, color, sound; 22 min. Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist and 47 Canal, New York.

3. Support New Work

Of course, site-specific work couldn’t happen without one of the Whitney Biennial’s most marked characteristics: that most of the works are new commissions. And supporting the production of new work means that artists can experiment with new technology.

In the past, the biennial has come under fire for being too in thrall with technology, at the expense of the work’s quality. This year, there were tech-heavy works that proved an exception to this. Anicka Yi’s 3-D video The Flavor Genome exploits the effects of this format for a deeply sensory experience—as the film’s “flavour chemist” hunts through the Brazilian Amazon for a mythical plant, images of modified fruit and flavour experiments flash across the screen, hypnotically. At one point, I could swear I smelt the swampy scene Yi was describing.

At other points, this immersive quality of technology was used to more disturbing ends. Jordan Wolfson’s virtual-reality piece, Real violence, was set up simply on a table, with VR headsets and little warning of the piece’s content: a life-like city scene, where, just ahead of you, Wolfson picks up a baseball bat and brutally, inexplicably attacks another person; a recording of Chanukah blessings is audible alongside the victim’s screams and crunching bones. The results are sickening, and I’ve found myself struggling to find any possible account of the work that isn’t simply an indulgence of barbarism.

In other cases, commissioning something means you won’t get a work at all. Cameron Rowland asked the Whitney to invest in a Social Impact Bond for his contribution, which displays the resultant documentation. “Typically used by city or country government as austerity measures, these bonds privatize social services… As of February 27, 2017, the Museum entered into an Agreement with Social Finance, Inc., and transferred funds to a Pay for Success project intended to reduce the rate of adult incarceration,” explained the didactic text.

4. It Might Be Hard to Preserve, and That Might Be Alright

If you’re following any New York art-news outlets on social media, by now you will have seen the bologna. Unless you made the trek to the meatpacking district, though, you will not have smelt the bologna. Pope.L, aka William Pope.L, has built a miniature gallery of his own in the second floor, a simple room painted in rose quartz and mint (just a shade or two off Pantone’s colour of the year in 2016), and affixed 2,755 pieces of the meat, a favourite in delis across the country, to its walls. Each one, we are told, bears a black-and-white portrait which supposedly corresponds to one of New York’s 1,086,000 Jewish residents. The numbers, and who precisely is depicted in the portraits, is up for debate, but the work’s staying effect—that haunting, fleshy, decaying scent—is not. Even almost 24 hours later, just looking at the photograph on my phone is enough to trigger a visceral sense memory.

Not every work with organic matter was quite as confrontational. Harold Mendez’s American Pictures (2016) was beautifully quiet: wrought iron carrying a piece of wood coated in crushed cochineal insects (whose pigmentation works its way into everything from red food to lipstick), all scattered around with carnation petals. The petals will be replenished by the gallery at intervals, offering a little ritual every now and then. In the meantime, the collections department will likely be working full tilt, figuring out a way to keep all this work intact once it heads to the vaults.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, production photograph for The Island, 2017. Ultra-high-definition video, colour, sound, 42:05 min. Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, production photograph for The Island, 2017. Ultra-high-definition video, colour, sound, 42:05 min. Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist.

5. Large, National Surveys Need Sensibilities, Not Prescriptions

The groundwork for large art productions like the biennial is built years in advance, which makes responding to rapidly changing current events—even in a tertiary manner—difficult. As Lew and Locks acknowledged in their opening press-preview remarks, when they started working on the show in 2015, there was no sense that Donald Trump would be elected president, or that the national divisions and tensions would be made as obvious as they have become in the last year.

And yet, while the show makes no grand claims to offer some kind of deep resistance or response to the current political climate, a clear awareness of the moment is embedded throughout: in Henry Taylor’s painting of Philando Castile, fatally shot by police; in Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s drawings and paintings of white poverty and Trump supporters at a rally. Even works that don’t draw a direct line to the recent election, like Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s video work depicting a dystopian future on Pulau Bidong, which housed the largest refugee camp after the Vietnam war, or Lyle Ashton Harris’s installation, which monumentalized personal snapshots and diaristic videos, hold lessons.

Ultimately, this year’s Whitney Biennial offers a snapshot of work that is occasionally uneven, but, on the whole, thoughtful and elegiac—which is perhaps as much respite as an exhibition can offer.

Caoimhe Morgan-Feir is associate editor at Canadian Art.

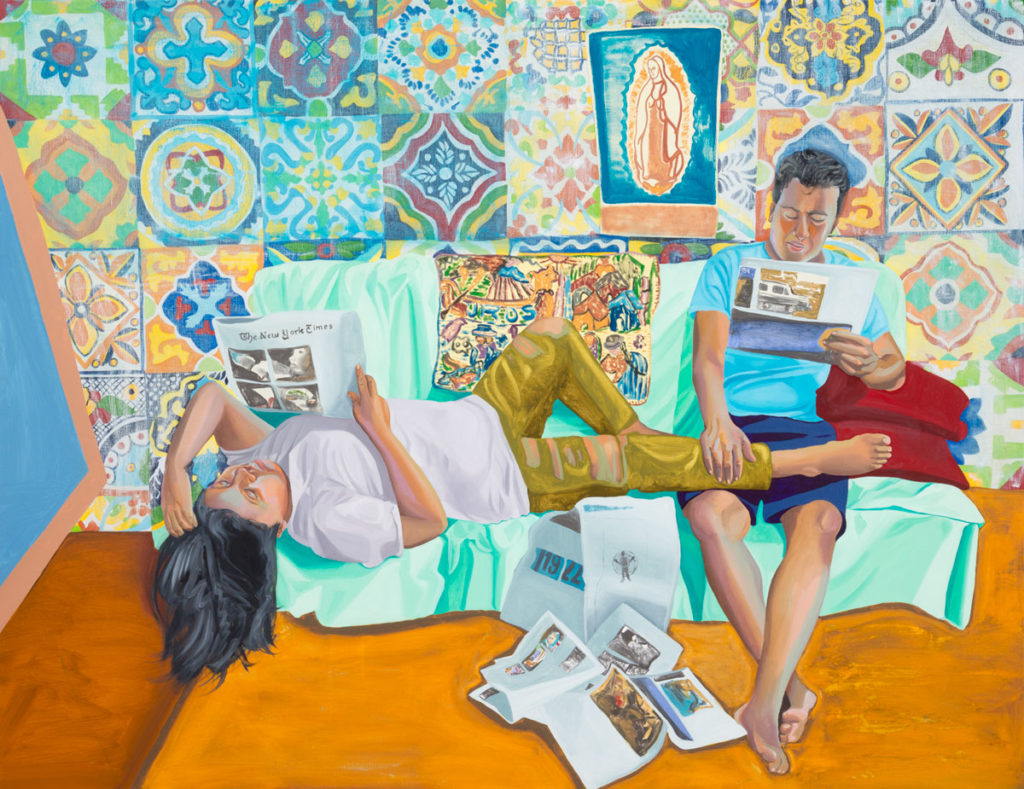

Aliza Nisenbaum, La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016. Oil on linen, 68 × 88 in. (172.7 × 223.5 cm). Collection of the artist; courtesy T293 Gallery, Rome and Mary Mary, Glasgow.

Aliza Nisenbaum, La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016. Oil on linen, 68 × 88 in. (172.7 × 223.5 cm). Collection of the artist; courtesy T293 Gallery, Rome and Mary Mary, Glasgow.