A photograph by Joseph Strohan, currently featured in “A Terrible Signal,” an exhibition on darkness at Access Gallery.

A photograph by Joseph Strohan, currently featured in “A Terrible Signal,” an exhibition on darkness at Access Gallery.

I’m living next to a graveyard, sleeping in the quietest bedroom I’ve had to date. In the mornings, I hear only distant traffic, sporadic caws, rain drizzle and the periodic buzzing tones of my space heater cutting in. Staring up at the ceiling without my glasses, blurred highlights and contours echo muffled sounds in visual form. When Vancouver skies are overcast, the dulling begins like this in the early hours and persists, a cloaking mist, until evening.

“A Terrible Signal” at Access Gallery features recent work relating to darkness by Vancouver-based artists Megan Hepburn, M.E. Sparks, Daniel Phillips, Carolyn Stockbridge and Joseph Strohan. The curatorial premise is evident at first glance, the gallery space punctuated with dark, rectangular shapes—several oil paintings on canvas, murky silver gelatin prints and a heavy-curtained video booth. Director/curator Kimberly Phillips, in her exhibition essay, proposes the darkness here as representative of a density of information, rather than a void or lack.

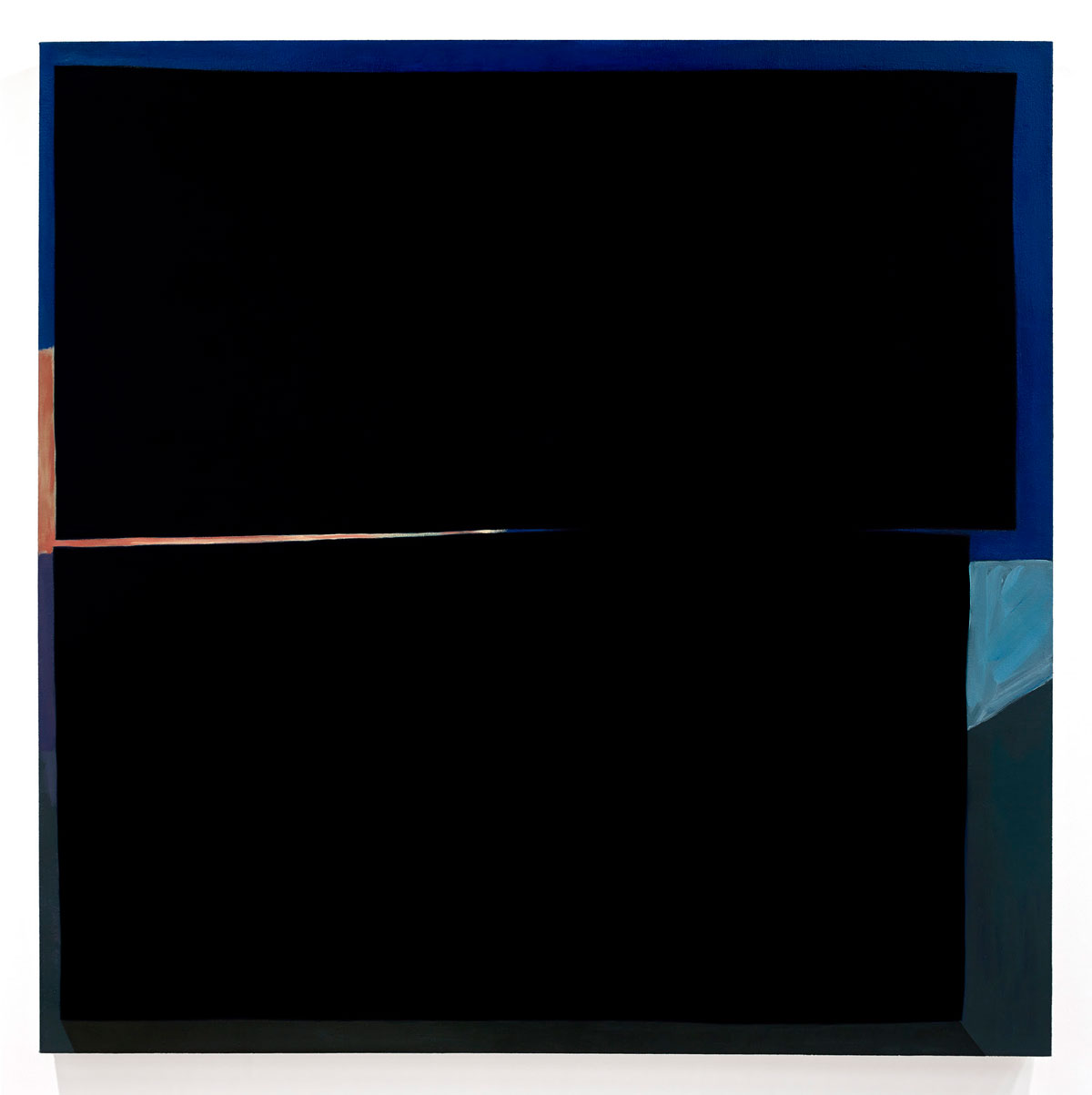

Chromatic black comes to mind, a painter’s hue achieved by blending pigments, allowing for subtly perceivable complexity of colour not afforded to flat mars or ivory black. Its metaphor is most obviously conjured by the commanding form in M.E. Sparks’s painting Pitch Apart (2016), where applied layers have gradually amounted to a domineering shadow, covering preceding gestures—save for the painting’s edges, and in one bright, bisecting slice.

M.E. Sparks, Pitch Apart, 2016. Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Collection of Sara Safran. Image courtesy of the artist.

M.E. Sparks, Pitch Apart, 2016. Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches. Collection of Sara Safran. Image courtesy of the artist.

Joseph Strohan’s small photographs, taken at night without flash, depict banal details from residential streets—dim views of doorways, vehicles, fences and minor landscape elements. While limited in visual information, they convey a compression of time—a compression articulated through the images’ implied wandering, and the scant lighting that would necessitate long exposures.

Megan Hepburn’s painted abstractions are often referred to as “luminescent,” but “incandescent” is a more appropriate descriptor for When this dance is done (2015) and Leave-taking (2016), each simmering warm like compost heaps, halfway through becoming deep soil. Vacillating with finger-like marks of matte and dark gloss, their glowing colour is emphasized by the other monochromatic works in the room.

Carolyn Stockbridge’s decided shift from a colourful to a black palette in 2013 distills a personal narrative: her grief response to great loss that year. The exhibition essay informs us that the shift included a painting-over of preceding works, an intentional obfuscation not quite like burning an oeuvre—the previous paintings are rendered inaccessible, not obliterated. While the large, slick-looking duo here do not entomb ancestors, they reach for them with an unsettling ache.

The Flayed Man (2015), a single-channel video by Daniel Phillips, is the work in the exhibition with the most lasting impact. Its partitioned booth and headphones accommodate an audience of one—a shutting-out that forces prolonged attention. As the camera pans a darkened domestic space, the video employs a number of low-production cinematic tropes, such as views through peepholes, a lagging focus and a voice-over by way of covertly recorded phone call.

The exhibition’s title, drawn from the lyrics of “The Overload” (1980) by the Talking Heads, is apt here. Conveying at first an informal ease with its uncomplicated gestures, however moody, The Flayed Man grows increasingly disconcerting, amounting to a series of foreboding signs that overshadow the desire for narrative coherence. A frantic bird, an alarmingly sudden drip—this imagery returns to me in the following days.

In foreground: Ann Lislegaard, Oracles, Owls… Some Animals Never Sleep (installation view), 2012–14. In background: Neil Wedman, House of Mirrors #2 (installation view), 2014–15. Courtesy Or Gallery.

In foreground: Ann Lislegaard, Oracles, Owls… Some Animals Never Sleep (installation view), 2012–14. In background: Neil Wedman, House of Mirrors #2 (installation view), 2014–15. Courtesy Or Gallery.

The sister exhibition to “A Terrible Signal” is “Uncertain Reflections” at the Or Gallery, curated by Mark Lanctôt and Jonathan Middleton, and featuring works by Ann Lislegaard and Neil Wedman. Both exhibitions are part of an ongoing series, conceived by Lanctôt and Middleton, titled “The Troubled Pastoral,” and the thematic links between them are apparent.

House of Mirrors #1, #2, and #3 (2014–15) by Wedman are towering oil-on-canvas paintings featuring straightforward views of empty mirror mazes. As with actual attractions of this kind, the images are arduous to navigate without identifiable reference points, such as the manifold bodies of beguiled beholders. The excessive multiplication of represented mirrors is confounding, amounting to a blinding density of information. They become hidden in plain sight, retreating into the materiality of their accumulated brush strokes, washes and tape lines.

The owls in Lislegaard’s video installation Oracles, Owls… Some Animals Never Sleep (2012–14) are the menacing overlords to the startled budgie that appears in the Phillips video at Access Gallery. They are at once amusing and terrifying, barking clipped phrases taken from the I Ching, glitchy with mechanical chirps and growls. Identical, the pair move together, but adequately out-of-sync so as to produce a specific distrust. While familiar in some regard, their ability to replicate, and to disappear and reappear in fitful intervals, prophesies part-mechanical beasts that can exceed natural limits.

Walter Scott with astrologer Kelly Benson, who was reading Wendy’s Natal Birth chart for the launch of Scott’s graphic novel Wendy’s Revenge. Courtesy 221A.

Walter Scott with astrologer Kelly Benson, who was reading Wendy’s Natal Birth chart for the launch of Scott’s graphic novel Wendy’s Revenge. Courtesy 221A.

From prophecy to divination—consulting astrologer Kelly Benson recently performed a natal birth chart reading at 221A for Walter Scott’s fictional character Wendy. The occasion: to celebrate the launch of Scott’s second graphic novel, Wendy’s Revenge (2016). The abundantly post-millennial crowd in attendance responded with a collective chuckle as Benson answered Scott’s questions concerning Wendy’s career, love life and friendships. “She’s a real wildcat,” Benson offered.

Wendy’s Revenge, published by Koyama Press, follows our charmingly fallible protagonist as she travels from Montreal to the West Coast to Tokyo, continuing her ongoing pursuit of art stardom and self-discovery. Subsections feature the independent storylines of recurring characters and friends—notably that of Winona, fellow artist and Wendy confidant, who returns for a time to her mother’s Indigenous community in “Back on the Rez!” While injecting the novel with more discernible Indigenous perspective, Winona’s chapters stay on brand, still largely about navigating interpersonal relationships, text-message interpretation and art-world anxiety.

This novel, in many ways, mirrors Scott’s own personal and artistic trajectory, which is why his insights resonate so successfully with readers—the books brim with a lived authenticity and with thinly veiled real-world references, easily decipherable by those in the know. Scott, like Wendy, spent a recent period of time as a Vancouver resident, and the playful jabs at the city in Wendy’s Revenge start early—a welcome sign boasts a population of 700, and Winona, who greets Wendy when she arrives, drops candida-cleanse and kombucha buzzwords. Later, when they speak on the phone, Wendy asserts “I don’t know how you could live here,” to which Winona replies, “Yeah, it’s a bit vibey.”

There were ample vibes at a February 21 performance by Hubbub, “a foray into experimental acoustic and electronic music” featuring voices, theremin, electric cello and a small collection of glassware. The performance was part of D.B. Boyko’s contribution to the sparse exhibition “Noise gives the listener duration as an artifact,” on now at Artspeak, and also featuring work by Gabi Dao and Steve Hubert.

Hubbub’s improvisational concert saw Boyko, joined by musician Christine Duncan and interdisciplinary artist Andreas Kahre, serenading the audience with lyrics only ad-libbing could spawn—notes on Instagram and cannibalism emerged, along with the rhythmic invocation of gallery staff by name.

Director/curator Bopha Chhay’s exhibition text frames the Hubbub trio as playing the reverberations of Artspeak’s space, which inevitably also includes sonic bleed from the artist-run centre’s lively Gastown locale. A high-pitched vocal shriek was answered by a passing police siren at comparable frequency, and the event’s last sounds, apart from applause, were the dragging clinks of glass bottles in the street.

Gabi Dao, Curled Up In a Spiral, 2017. Photo: Dennis Ha. Courtesy Artspeak.

Gabi Dao, Curled Up In a Spiral, 2017. Photo: Dennis Ha. Courtesy Artspeak.

Dao’s Curled Up In a Spiral (2017) and Polished Like a Shell (2017) are resin-coated sculptures of seashells, pigmented with soap and eyeshadow, on polystyrene-oval platforms with vintage portable radios. They transport me to 1980s bathrooms in pastel seashore themes, with scallop-shaped sinks and perfumed bath-oil beads.

Playing from each sculpture is the audio work Voices Tuned (Like a Native Speaker Speaking, 1988) (2017), in which Dao responds to recordings of her mother practicing English, reflecting on the lineage of her own speech and likening the wound-up tape of the found cassette to spiral forms of seashells and to depictions of the Tower of Babel. As Dao’s mother sounds canned phrases and disconnected monologues to a tapping metronome, I picture the calculated movements of her mouth as though magnified by vanity mirror.

The exhibition text refers to Hubert’s The Rich Interior Life II (2015–17) as “a mind map that sketches out the process of listening.” An assembled web of unceremonious shapes in wood, Plexiglas, concrete and other materials, the work encapsulates spontaneity similar to that of Hubbub’s live performance.

Poster Designs 1–6 (2017) are ink on translucent paper; Hubert made them by loosely tracing movie posters displayed via underlying, glowing screen. During Boyko’s second in-gallery live event, an embodied listening workshop session titled The Empty Vessel Makes the Loudest Sound, I stare up at the ink drawings while wearing her distributed earplugs. A convergence of deliberate mufflings occurs, both gestures serving to highlight alternative ways of mapping rhythm.

Finally, in the late evening hours of a Tuesday in February, I headed to artist Casey Wei’s monthly curated program at the Astoria pub titled Art rock?, presenting its 16th iteration since 2015. The series showcases experimental practices that demonstrate aspects of blurring music and art, all within the casual atmosphere one would expect from a local bar gig. While easygoing in her approach to ambiance, Wei is unwaveringly committed to documentation, meticulously recording each performance, which she catalogues and publishes online under the YouTube username beepa boopo.

Facilitating multidisciplinary contexts for artists and musicians, Art rock? also navigates the expectations of inadvertent patrons, which is part of its charm. Catching Wei at the door, I overhear a conversation with a chance attendee weighing the evening’s modest cover charge. “Is it any good?” the woman asks. It is good. While sipping bottles of Pilsner on special, I listen to successive acts death.drive, SAUCE and Puzzlehead, until the day’s fog gives way to a numbing beer buzz, a rousing pulse and the swirling flash of coloured stage lights on checkered tile floors.

Lucien Durey is an artist based in Vancouver. His performative works engage with collections, found objects and ephemera.

This post was corrected on March 9, 2016. The original post referred to Megan Hepburn’s painting Goat Hair (2016) when actually intending to refer to her painting When this dance is done (2015).

A photograph by Joseph Strohan.

A photograph by Joseph Strohan.