There are a few pieces of art that conjure up “home” for me, and Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) is one of them; not only for the domestic space in which Rosler enacts her anxious kitchen demo, but for my deep familiarity with the work, which was cited constantly throughout my undergraduate education. Rosler’s seminal video is the wellspring from which so much feminist work has grown, and its central placement in “Un-home-ly”—a show dealing with contemporary feminist media-art practices that filled the Oakville Galleries’ two locations—spoke to the depth and wit of the curation of Matthew Hyland, the galleries’ director.

The show, which promised to be the first of several exhibitions exploring contemporary feminist art, was premised in part on Sigmund Freud’s seminal notion of the uncanny. With this particular collection of artists, Hyland zeroed in on a sense of vague unease. The two galleries were replete with women casting a troubled eye on the ways in which they are allowed to fit in to their milieux; the atmosphere of “Un-home-ly” was not unlike the first act of a horror movie, in which something indefinable is ineffably askew.

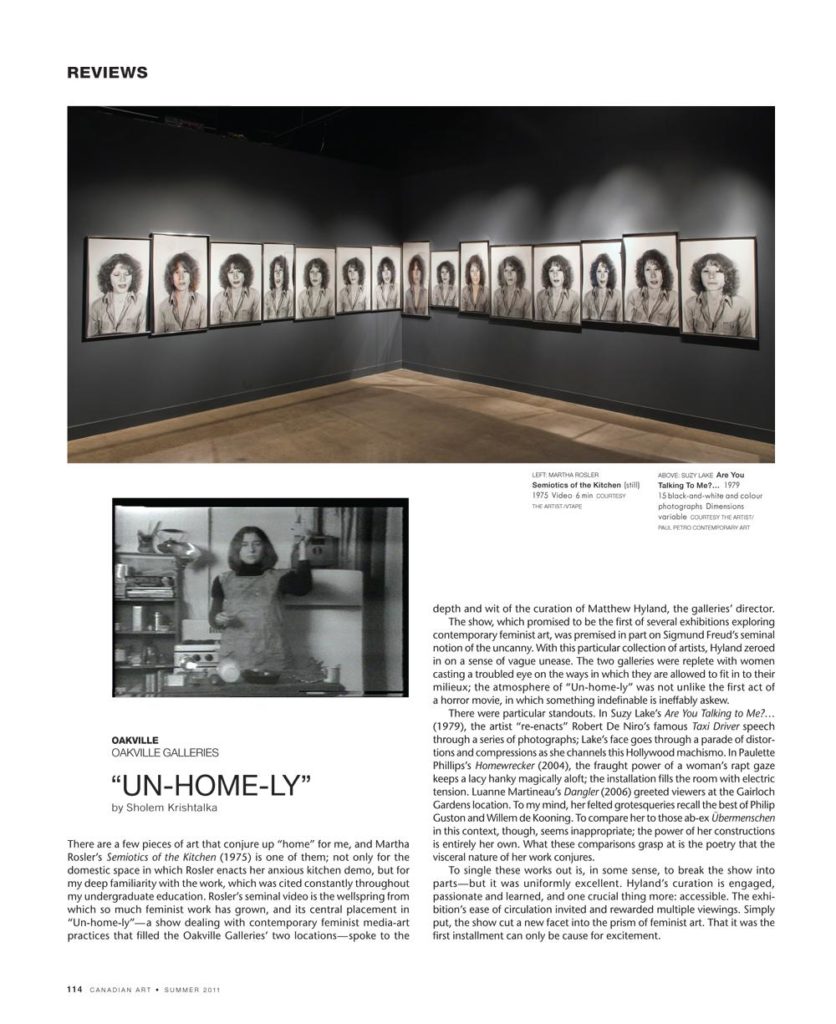

There were particular standouts. In Suzy Lake’s Are You Talking to Me?… (1979), the artist “re-enacts” Robert De Niro’s famous Taxi Driver speech through a series of photographs; Lake’s face goes through a parade of distortions and compressions as she channels this Hollywood machismo. In Paulette Phillips’s Homewrecker (2004), the fraught power of a woman’s rapt gaze keeps a lacy hanky magically aloft; the installation fills the room with electric tension. Luanne Martineau’s Dangler (2006) greeted viewers at the Gairloch Gardens location. To my mind, her felted grotesqueries recall the best of Philip Guston and Willem de Kooning. To compare her to those ab-ex Übermenschen in this context, though, seems inappropriate; the power of her constructions is entirely her own. What these comparisons grasp at is the poetry that the visceral nature of her work conjures.

To single these works out is, in some sense, to break the show into parts—but it was uniformly excellent. Hyland’s curation is engaged, passionate and learned, and one crucial thing more: accessible. The exhibition’s ease of circulation invited and rewarded multiple viewings. Simply put, the show cut a new facet into the prism of feminist art. That it was the first installment can only be cause for excitement.

This is an article from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.