Begin with the big picture, the largest frame. Tomorrow moved from Toronto to New York by way of Berlin. Its director, Tara Downs, founded the gallery in 2011 with Aleksander Hardashnakov and Hugh Scott-Douglas on Toronto’s Sterling Road. Eventually operating solo, Downs kept Tomorrow remote while clocking hours at Tanya Leighton Gallery in Berlin. Downs then properly set up shop in New York with “Eternal September,” an inaugural group exhibition that closed on October 5.

Then zoom in. “Eternal September” featured works by a number of local figures like Oto Gillen and Bradley Kronz, but also some by Mary Ann Aitken, who died in 2012 at age 52. Downs mentioned to me that she was interested in distancing Aitken from what she saw as Aitken’s outsider status, which I found an intelligent choice.

Now, zoom out. As Downs outlined to Art in America’s Nick Irvin, the show’s title refers to a historical moment in the Internet’s development. In September 1993, AOL expanded access to Usenet, an Internet discussion network, and thus broadened their typical customer base of university freshmen to include millions of new users. The result was waves of people perpetually finding their bearings, learning not only the skills of proper technological navigation but also the conventions and customs of e-discourse. The frame grew larger and the content wilder.

With this Internet-historical citation, “Eternal September” threatens to evoke the fashionable over-summoning of outdated cybertechnologies that characterizes so much Internet art and criticism. (It’s not for nothing that Tomorrow’s current show features Brad Troemel.) But Downs’s curatorial touch is light and sophisticated enough to avoid this. Rather, the show treats the digital as one aspect in a multitude of exhibitional apparatuses: Downs’s multimedia combo assembles work on canvas, wood, cardboard and through a readymade. If the historical Eternal September saw techno-novices adjusting to an entirely new frame of reference, then “Eternal September” refracts that angle. It takes on the way frames guide how we know things, and obscure them in equal measure.

Zoom in to each frame, starting with the broadest. Downs organized the exhibition into a series of pairs, of which Jason Matthew Lee’s stands as the most engaging. Towards the gallery door—it’s a small, narrow space—Lee installed a standard payphone high on the wall and placed curved text around the entrance with a handheld printing gun. The text, slightly illegible, hints at some mnemonic deficiency, beginning, “I reiterate that because the memories or apparent unfolding of events was nonsequitur.” The payphone symbolizes bygone communication in an analogue to the show’s title. Yet more contemporary technologies appear in Lena 1 (2014), an inkjet of intentionally dubious execution in which a nude model appears in kaleidoscopic disarray and scattered chromatic layers disfigure a faintly visible URL line, among other objects. Technology doesn’t behave like it’s supposed to in Lee’s work at Tomorrow, whether in the confusing words snaking around the architectural frame of the gallery or the techno-formlessness of Lena.

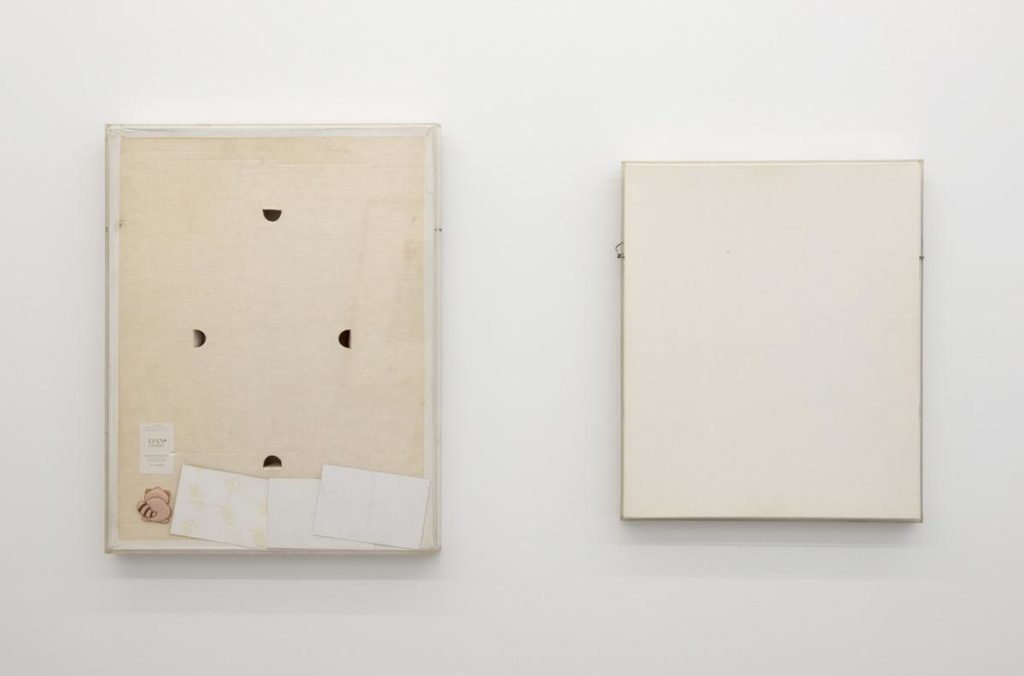

Framing is somewhat more explicit in the pair by Bradley Kronz. Two untitled works from this year physically reverse their presentation. Kronz frames the back of acrylic boxes directly on the wall, hinting at the box’s inside, which is cut off from view. He inverts the frame and sets off a whole host of queer, metaphoric reversals: on one of the boxes, we see the back with four indentations, the ass of an illustrated raccoon and a label indicating, “To remove place finger in hole, spread side, and pull out.” The erotics are heavy-handed and with the fairly lackadaisical arrangement, the untitled pieces condense into a series of references without formal dynamism.

Oto Gillen emphasizes the work of his frames more. His handcrafted wooden borders distort the proportions of his mats so that the centering of his images goes askew. The stoic conceptualism of one his pieces, which features two black-and-white photographs of a palm tree, first prostrate then erect, clashes with the larger off-kilter presentation. In that same piece, a computer inside the frame runs an LED light that inconspicuously flashes in intervals. It’s a bit too minimal to affect anything in the artwork, but Gillen’s addition of the computer touches on the exhibition’s interest in relegating action to the frames.

Downs selected three works by Mary Ann Aitken that are dissimilar in immediate appearance but connected, again, by frame. Her canvases utilize sand, resin and glass. In the most intriguing work (and in counterpoint to Gillen’s palms), Aitken painted over the mat, frame and photograph under display. The two images of Untitled (crosswalk diptych 1) (2012) show people and cars at a crosswalk. The slanted external perspective implies observation, maybe voyeurism. But it’s all obfuscated by oil—the visual borders between parts of the artwork, from its “material support” (as Rosalind Krauss would call it) down to its recorded content. If the ways of seeing in Aitken’s work are murky, so are their results.

Zooming out again, more broadly. It’s hard not to think of the passe-partout, or the French word for the mat between the image and the frame. For Jacques Derrida, the passe-partout was the structural in-between zone, at the midpoint of “content” and “context” (passe-partout also means “master key,” the way in to all things closed). “Eternal September” collects treatments on the passe-partout of visual representation, some more sophisticated than others. (There’s a sculpture, by Valerie Keane, of a professionally fabricated steel form, whose interjection in space feels lopsided in the architectural context of the show.) But as their first foray into New York, “Eternal Summer” shows Tomorrow as a gallery with promise—with the right frame of reference.