The Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art has an identity crisis. Well, maybe not an identity crisis so much as a locational crisis. After a decade on Toronto’s Queen Street West—a move that brought the gallery to the then-heart of the city’s art scene from the reaches of North York—MOCCA’s building lease is nearing its end. By this time next year, the gallery will be in a new home. The question is: Where will that be? At last word, the search for an appropriate space continues amid the ever-rising prices and competition in Toronto’s booming and inflated downtown property market.

An equally compelling question for the gallery’s board of directors and staff, not to mention the country’s contemporary artists, is how that future home will determine what MOCCA is or can be. Without the deep pockets of the Art Gallery of Ontario or the international ambitions of the Power Plant, MOCCA has long struggled to define itself at the top tier of Toronto’s cultural scene. There is a certain spontaneous freedom to that in-between position which has often given MOCCA and its tireless director, David Liss, the opportunity to program outside of rote institutional expectations. But with that flexibility comes unpredictability, a seemingly unavoidable circumstance that is at once MOCCA’s greatest strength, and its weakness.

“TBD,” the current feature exhibition at MOCCA, offers a case in point. Organized by the gallery’s assistant curator, Su-Ying Lee, the exhibition is designed, in light of MOCCA’s pending relocation, as a conceptual study of the ranging possibilities of a modern contemporary-art institution. It’s a show that promises to both disrupt and expand the often-restrictive definitions of an exhibition’s premise and premises, and to examine how those redetermined conditions relate both to location and community. As Lee puts it in the exhibition press release: “Contemporary art museums must be self-reflexive and self-motivated towards evolving, asking: How is a contemporary art gallery defined? What is the art institution’s function in society? Are contemporary art galleries, as they permanently exist, relevant?”

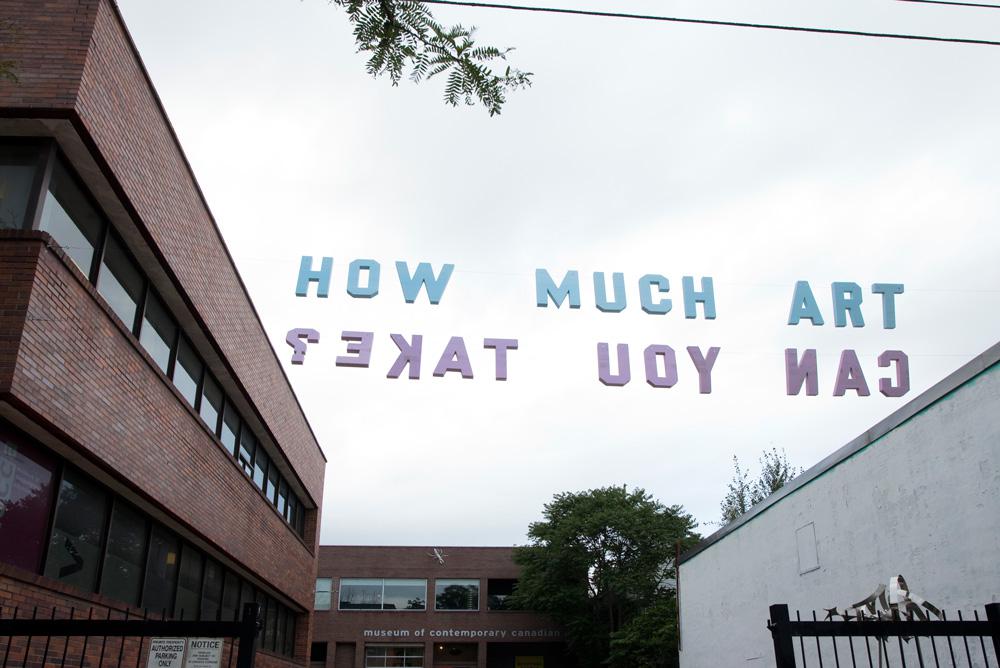

These are key questions for any contemporary art institution. But how they surface in Lee’s exhibition is a mixed affair. To start, Jesse Harris’s partially reversed Styrofoam text work How much art can you take? (2014) is cleverly installed dangling from (or clinging to) power lines above the courtyard entrance to the museum. It could be a comment on the precarious relationship between art and the conduits of institutional power, and the work’s lightweight materiality is possibly both a practical measure and a jab at the commodity value of art-world expectations. But aside from a prime social-media photo-op for visitors entering and exiting the exhibition (In the 15 minutes I spent looking at the work, I saw three different groups posing for pictures under the text), it’s hard to see what this rhetorical play says beyond, well, what it says. If anything, it carries an implied challenge in the anticipation of what’s ahead when you enter the show, then rubs in a kind of post-visit malaise as you walk past the work on the way out, perhaps offering a not entirely intentional answer to Lee’s question on relevancy.

For the museum itself, Lee and her architectural collaborator, Jennifer Davis, have created a new entryway into the main exhibition space, a clear path (and sightline) from the gallery’s doors into the show. For those familiar with the gallery, it is a surprising gesture that rationalizes the space, making it more accessible and open, and putting the initial emphasis back on the work on view instead of the museum foyer. Indeed, you wonder why MOCCA hadn’t done this long ago. There’s an intentional link here to the structural interventions of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Conical Intersects (1975), examples of which follow in three photo collages from the series on loan from the Canadian Centre for Architecture. But that’s a hard comparison to pull off: where Matta-Clark’s cuts radically deconstructed the densely built barriers of urban life, this new entryway seems merely pragmatic. That said, Lee and Davis’s action seems absolutely daring in comparison to the serial monotony of Dax Morrison’s Shop Series, which features architectural renderings of major Canadian museums highlighting space given over to gift shops.

Frustrating, too, was Justin A. Langlois’s Glossed Over (2014), with its white-vinyl-lettering-on-a-white-wall display of quotations drawn from the writings of Jean Baudrillard, Michel Foucault, Sol LeWitt and Jacques Rancière, among other notable thinkers on society and art. If there is meaning in this, it remains hopelessly elusive. In Jonah Brucker-Cohen’s Alerting Infrastructure! (2003), a hand drill mounted high against the gallery wall is activated by hits to the MOCCA website, theoretically destroying the wall as the virtual visits to the gallery mount. It’s a fine idea, and even though there were technical difficulties with the work when I visited the gallery, there was much promise to the minor destruction already underway. Yet I quickly found out that Brucker-Cohen’s drill is fixed, so that it merely spins in a single, pre-determined spot and depth, the surrounding gouges and holes in the gallery wall being simply cosmetic. Why render this work impotent and false when it has such forceful potential? And I still haven’t found my way to the tattoo shop with a small pine bench as described in the loosely mapped instructions of Arabella Campbell’s Ways of Seeing by Walking (2014). I’m starting to think (or hope, for the sake of the work) that maybe it doesn’t exist.

Maggie Groat’s sculpture-cum-discussion-table Fences Will Turn Into Tables (2010–13) is exactly what its title suggests. No doubt the work is designed to summon some kind of potential energy for greater democratic good, though on viewing it sitting empty in the gallery, one imagines it looking quite smart in a collector’s dining room. A better place for Groat’s table might be at the Brewality of Fact Beer Club, a series of micro-meetings during the exhibition facilitated by Gina Badger, the STAG Library collective and cheyanne turions, though this promises to be no less exclusive as these brew-club/discussion sessions (with the exception of a final members-only meeting at MOCCA) are limited to a small group of pre-registered participants and take place at turions’s private home. There’s something deeply paradoxical about closed-door collective action and it’s not clear how that makes a viable prototype for realigned institutional futures.

Lee has opened up the “TBD” debate to a wider public with a program of panel discussions, a critics forum, unconventional exhibition tours (a “blindfolds” and “wall + outlets” tour, both on October 19) and weekly performances by artist Jon Sasaki that take a new measure of gallery attendance protocols and tracking for the duration of the exhibition. And despite the troublesome aspects of some of the works in the show (one wonders, too, how much that had to do with the realities of trying to make the most of a lean exhibition budget, a not-unimportant consideration in this context), Lee should get full credit for providing a public opportunity to take a critical look at where art practices and institutional thinking are headed in advance of MOCCA’s eventual relocation.

All this leads to perhaps the most interesting and I think successful aspect of “TBD,” the open invitation in advance of the exhibition to submit architectural proposals based on the question “What is a contemporary art gallery?” The resulting installation, To Be Destroyed: A call for ideas, gathers 69 of those one-page submissions mapping a future MOCCA; these range from itinerant satellite exhibition venues housed in disused buildings across the GTA to personally customized virtual-art environments. Whether there’s anything realistic to any of this is another question, but in the end it doesn’t really matter. The value in this work is its engagement, an inclusive effort to give the random energies of public debate a say in the all-too-often exclusive process of artmaking and institution-building. The results may be wild and unpredictable but, after all, that’s exactly what MOCCA does best. Whether “TBD”’s radical propositions will lead to real institutional change remains, as it were, to be determined.