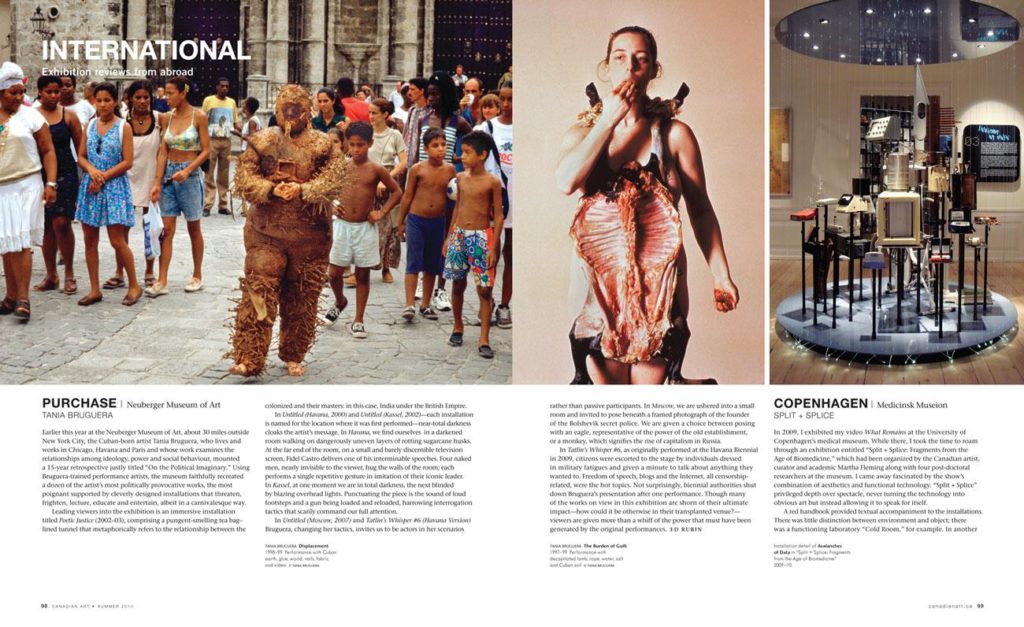

Earlier this year at the Neuberger Museum of Art, about 30 miles outside New York City, the Cuban-born artist Tania Bruguera, who lives and works in Chicago, Havana and Paris and whose work examines the relationships among ideology, power and social behaviour, mounted a 15-year retrospective justly titled “On the Political Imaginary.” Using Bruguera-trained performance artists, the museum faithfully recreated a dozen of the artist’s most politically provocative works, the most poignant supported by cleverly designed installations that threaten, frighten, lecture, educate and entertain, albeit in a carnivalesque way.

Leading viewers into the exhibition is an immersive installation titled Poetic Justice (2002–03), comprising a pungent-smelling tea bag–lined tunnel that metaphorically refers to the relationship between the colonized and their masters: in this case, India under the British Empire.

In Untitled (Havana, 2000) and Untitled (Kassel, 2002)—each installation is named for the location where it was first performed—near-total darkness cloaks the artist’s message. In Havana, we find ourselves in a darkened room walking on dangerously uneven layers of rotting sugarcane husks. At the far end of the room, on a small and barely discernible television screen, Fidel Castro delivers one of his interminable speeches. Four naked men, nearly invisible to the viewer, hug the walls of the room; each performs a single repetitive gesture in imitation of their iconic leader. In Kassel, at one moment we are in total darkness, the next blinded by blazing overhead lights. Punctuating the piece is the sound of loud footsteps and a gun being loaded and reloaded, harrowing interrogation tactics that scarily command our full attention.

In Untitled (Moscow, 2007) and Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version) Bruguera, changing her tactics, invites us to be actors in her scenarios rather than passive participants. In Moscow, we are ushered into a small room and invited to pose beneath a framed photograph of the founder of the Bolshevik secret police. We are given a choice between posing with an eagle, representative of the power of the old establishment, or a monkey, which signifies the rise of capitalism in Russia.

In Tatlin’s Whisper #6, as originally performed at the Havana Biennial in 2009, citizens were escorted to the stage by individuals dressed in military fatigues and given a minute to talk about anything they wanted to. Freedom of speech, blogs and the Internet, all censorship-related, were the hot topics. Not surprisingly, biennial authorities shut down Bruguera’s presentation after one performance. Though many of the works on view in this exhibition are shorn of their ultimate impact—how could it be otherwise in their transplanted venue?—viewers are given more than a whiff of the power that must have been generated by the original performances.

This is an article from the Summer 2010 issue of Canadian Art.

Spread from the Summer 2010 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Summer 2010 issue of Canadian Art