Despite the clouds that still loom over the Spanish economy, PhotoEspaña, Madrid’s annual photography festival, managed again this year to produce a strong exhibition schedule. Two exhibitions in the deco-designed Círculo de Bellas Artes were “Him, Her, It: Dialogues between Edward Weston and Harry Callahan” and “Woman: The Feminist Avant-Garde from the 1970s: Works from the Sammlung Verbund, Vienna.”

Weston’s and Callahan’s fine-art photographs of nude women in nature have their own value. But when viewed just before the feminist exhibition, they neatly exemplified the problems that women artists have faced—the male control of art, generally, and the same control over representations of women, specifically.

Women, of course, made art before the 1970s, but it was only in that decade that they formed an art movement with some critical mass. Joining a cluster of radicalizing social and political activisms from the preceding decade, they applied the methods and media introduced by Conceptual art to their own feminist concerns.

Through the then-new forms of photography, performance and video (thought to be less weighted with old ideas), and using low-tech aesthetics, women of the era explored gender identity and its construction within art history and media representations. Curator Gabriele Schor calls these artists the “Feminist Avant-Garde.” Her selection of works by 21 international artists—including Suzy Lake, who moved to Canada in 1968—demonstrates their innovations and influence on contemporary art.

Many of Ana Mendieta’s works express female identity as biologically based and innate, aligned with the body of Mother Earth. In her performance film Burial Pyramid, Yagul, Mexico (1974), the artist lies buried beneath rocks in a green landscape. Heaving great, volcanic breaths, Mendieta pushes the rocks away from her body. One of the artist’s well-known photographic series documents her bodily imprints in different natural locations, such as a riverbank, as in Untitled (1978) from her Silueta Works in Iowa. On the other hand, six colour photographs, from a larger group of 36, show that identity is constructed and malleable. In Glass on Body Imprints (1972) Mendieta’s distorted body is seen pressed against Plexiglas. In its resistance to normative ideals of beauty and in its method, Mendieta’s series prefigures British painter Jenny Saville’s collaborative photographs of the same type.

Renate Bertlmann’s photographic series Tender Pantomime (1976) presents the horrific underside of “woman as nature.” The artist, dressed in black fetish-wear and covered from head to fingertips in prosthetic nipples, represents woman’s (supposedly) sole function—to pleasure and feed others.

Work by the late Hannah Wilke plays up (and sends up) her own female sexuality and its media representations. The print Marxism and Art: Beware of Fascist Feminism (1977) is a semi-nude pin-up that mixes poses signifying both masculine and feminine power: wearing a necktie, Wilke also covers her body with tiny, vulvic sculptures. (In some performances, Wilke made the latter from gum chewed by gallery visitors.)

A photographic grid by Croatian artist Sanja Iveković’s documents her performance Opening at the Galleria Tommaseo (1977). During the performance, Iveković engaged in intimate touch and direct eye contact with individual audience members, while the sound of her amplified heartbeat was played over speakers. The work clearly prefigures Marina Ambramović’s later performances, such as The Artist is Present (2010) that involve audiences in sensual communication.

In the 1970s, women artists wrestled over ownership of their image—they undermined oppressive media representations by taking them apart and playing with them. This exhibition shows their lively genealogy. Cindy Sherman’s early, rarely seen student work displays the deep roots of her later practice and the fact that she was influenced by earlier artists who used make-up and masquerade. Sherman’s black and white photo series Bus Riders (1976) is a prototype for her better-known Untitled Film Stills (1977– 80), with Sherman occupying the identities of individual commuters through costume and gesture. Similarly, her charming film Doll Clothes (1975) shows the artist as a small, underwear-clad cutout doll stored in a plastic folder. The doll escapes to try on paper outfits, but a giant, authoritative hand plucks her up and imprisons her back in the folder.

Eleanor Antin’s video Representational Painting (1971) is a subtle and complex work. For 38 minutes, the artist gazes at what viewers understand as a mirror, but is actually the camera lens. Occasionally, thoughtfully, she applies make-up. “She,” as central subject of art historical figurative painting, here inhabits the roles of painter and painted, at once image, object and subject. Duration is a prominent feature in this and related works, suggesting the weighty time investments required for women’s image management.

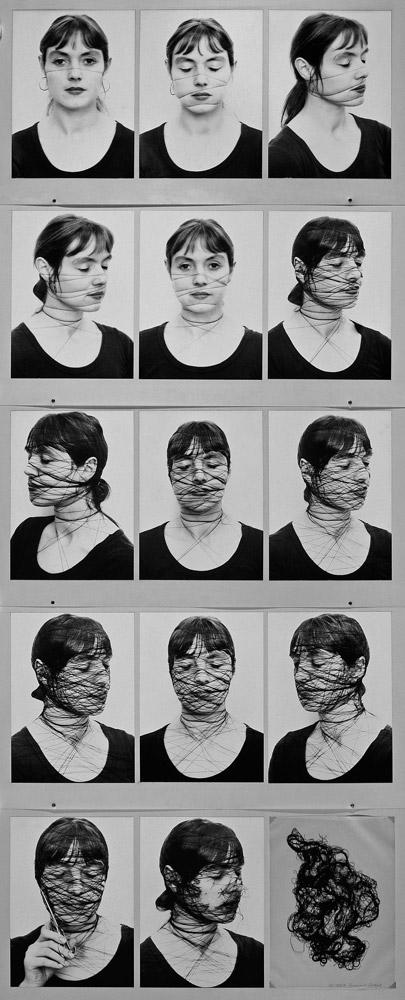

Seriality and the grid form are also common across many works; Suzy Lake uses these to playfully perform the construction of identity. Imitations of Myself (1973) is a grid of 48 colour photographs. In the first image, the artist blocks her face with a white sign that reads “Genuine Simulation of …” In consecutive images, her identity is emptied by “whiteface,” and is then remade as ideal feminine beauty. Lake also wears “whiteface” in Miss Chatelaine (1973), a grid of 12 small black and white photographs. Superimposed around each facial expression is a different hairstyle or hat culled from fashion magazines, creating a grotesque parody of the beauty ideals on offer.

Artists such as Martha Rosler tracked the ways that male-authored linguistic systems have shaped women’s lives. Her landmark Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) demonstrates the way language contributes to women’s confining domestic roles. Staged as a cooking show, the aproned Rosler’s deadpan performance grows increasingly violent as she calls out the alphabet and related kitchen utensils.

The neglect that late Austrian artist Birgit Jürgenssen’s intelligent and whimsical work has suffered received correction in Madrid. Her whimsical and stylish consideration of female roles is inflected with Surrealist playfulness. The visually and thematically tight FRAU (1972) outlines the role language plays in the control of women. The small black and white photograph shows the artist’s body, clad in black tights, contorted around the shapes of the red printed letters FRAU (woman).

Schor’s curation of this collection is based on her belief that these artists laid the foundation for much contemporary art that followed. Through her excavation project, she believes many more artists will yet be added to what some might call the “alternative canon.”