The conjoining of art and language is a cornerstone of postmodernity. Art and literature combine less readily. Hamilton artist Stephanie Vegh was commissioned by the Leeds College of Art to participate in an international exhibition of visual artists inspired by the Brontë sisters. With immaculate alterations of existing illustrations, or new illustrations for non-existent books, Vegh’s practice might be termed meta-illustrative, and as she holds a degree in studio art and comparative literature, she seized on the opportunity.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (published in 1847 under the pseudonym Currer Bell) is a bellwether of English literature. Its story of a thoughtful and forbearing orphan framed remonstrations about dominant stances on politics, gender, education and religion as England moved further toward an urban population and industrial economy. The novel’s rural settings illustrate a society at the edge of crisis. On page two of the book, Jane, while in the library of her aunt and warden, browses a copy of Thomas Bewick’s A History of British Birds, a then-standard ornithological reference book, only to have her cousin snatch it away and throw it at her in his fury at her handling property that does not belong to her.

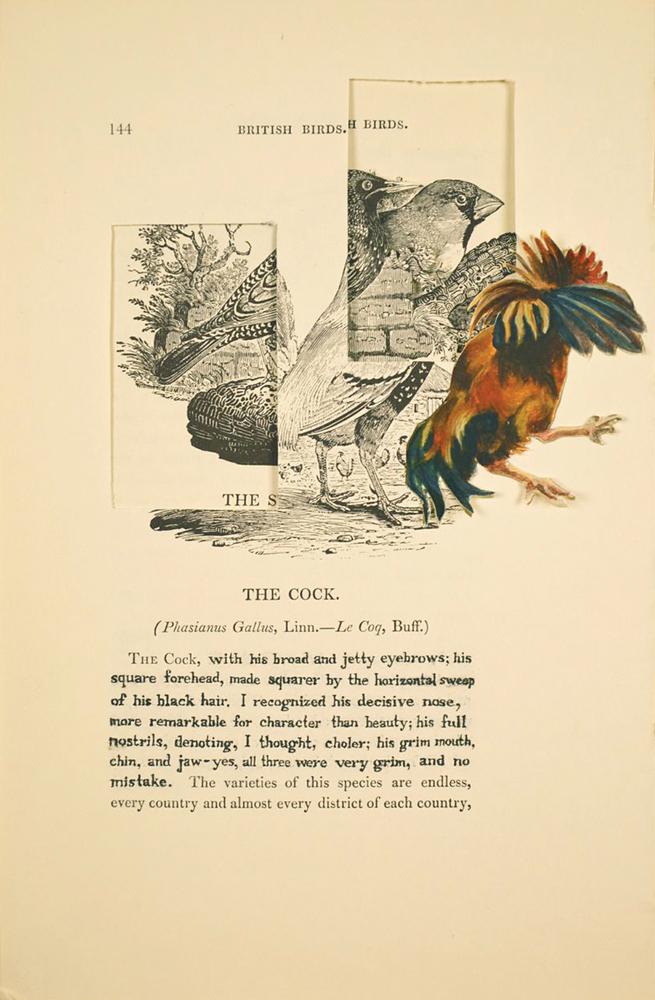

Vegh obtained a facsimile of Bewick’s book and went to work with scalpel and fine-bristled brushes. For each of the characters in the novel, Vegh selected a symbolically representative bird. Jane is the Female Short-Eared Owl, Alice Fairfax the Heron, and so on. Edward Rochester, the brooding alpha male, is the Cock. In A History of British Birds, each entry features a line engraving of the bird above its name, taxonomy and descriptive notes. Vegh defaced the illustrations by cutting rectangles to reveal other closely related or misleadingly heterogeneous species below. In detailed watercolour, she reintroduced the subject in flight from this genetically addled substrate. She also replaced each partially scraped-away typeset description with Brontë’s observations on the respective character. For example, “The Cock [Rochester], with his broad and jetty eyebrows; his square forehead, made squarer by the horizontal sweep of his black hair. I recognized his decisive nose, more remarkable for character than beauty…”

Vegh prevails by identifying with both author and heroine. Jane herself is something of an artist. Rueing her inferiority to a rival for Rochester’s affection, she imagines drawing her self-portrait in chalk “without softening one defect,” labelling it “disconnected, poor, and plain.” By comparison, she pictures painting her rival on ivory in “freshest, finest, clearest tints; [to] delineate carefully the loveliest face you can imagine….” Vegh combines both methods—objective caricature and idealized likeness—into one enigmatic analogy to a literary fact: we never see a face as envisioned by the author, but at best formulate a substitute or rely on the illustrator.

The very name Eyre underscores Vegh’s treatment. It reads like “eye,” or “eyrie” (a nest made on high) but sounds like “air”—invisible, everywhere, part of every breath.

This is a review from the Fall 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents.

Stephanie Vegh Edward Rochester/The Cock 2012 Ink and watercolour on book pages 23 x 15.5 cm

Stephanie Vegh Edward Rochester/The Cock 2012 Ink and watercolour on book pages 23 x 15.5 cm