While a life’s narrative is often described in terms of dramatic high points and low points, the more ubiquitous and familiar realities of our day-to-day lives can be the most difficult aspects of experience to understand. This much is suggested by “Movement Never Lies,” an exhibition by Toronto-based collective Soft Turns at O’Born Contemporary.

Soft Turns members Sarah Jane Gorlitz and Wojciech Olejnik use mundane materials to create artificial representations of recognizable things and spaces; these are then used in stop-motion animations. Working collaboratively since 2006, the duo’s meticulous attention to detail is manifested in stunning and labour-intensive video works that, like a haiku, point to a few related images or ideas. The light that casts a glow over the spaces they construct brings to mind the otherworldly atmosphere of white nights in Sweden, where Gorlitz completed her MFA at the Malmö Art Academy in 2011.

Since its birth, the photograph has sometimes been described as a static object that captures a moment in time: something that has been, but no longer is. Soft Turns’ stop-motion animations might be read as extensions of photography—in them, individual photographs are strung together in endless loops to create the illusion of movement and time’s passage.

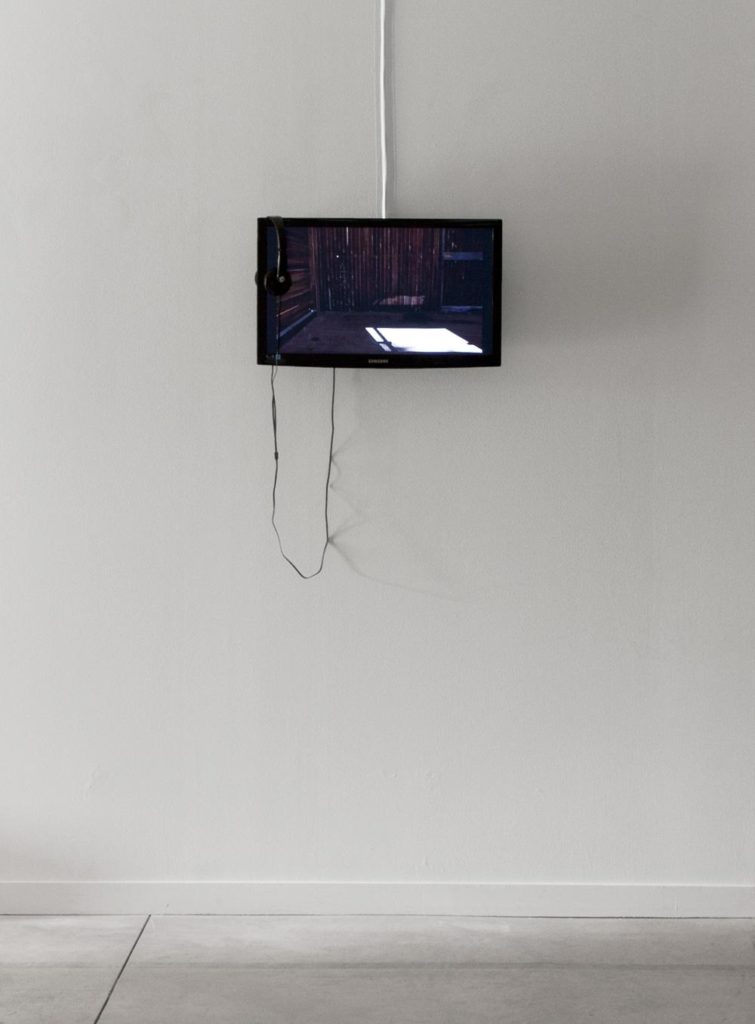

In A Passage (2010), the screen of a turned-off television mirrors and frames the reflection of a private living room. A projection of a moving train is occasionally superimposed on top of the screen to disrupt the otherwise peaceful scene. Public space and private space merge as the viewer attempts to make sense of the layers of reflective surfaces, with the train’s windows matching up to the ones of the living room. Train travel, like film and television, transports travellers out of the quotidian; in this anticlimactic and continuous loop, Soft Turns brings together the ordinary and the unusual to invite reconsideration of how we perceive and understand reality.

A journey on a train is also the starting point for Behind the High Grass (2011). In it, the quiet rumbles of a tranquil ride contrast with the bustle of a freight train’s exterior. Images of a boxcar’s interior corner—a space that invites introspection—are repeatedly disrupted by a noisy sequence showing the train from the outside. On the floor inside the train, the illusion of movement is created from a peaceful passage of a grey-scale landscape seen through a window. From the outside, the loud train accelerates rapidly. As the work seems to suggest, time is layered and diverse, and the world around us is composed of many speeds which often overlap.

In another work titled Just Add Water (2007), empty public spaces such as subway stations, corridors or platforms appear to be flooded at an unnatural speed. The miniature sets appear both strange and familiar; the artists used rectangular pieces of green gum to construct the tiled wall of a long, empty corridor in a deserted subway station, for instance. The work seems to invite meditations on how we occupy places of transience, sites where travellers might pause in between while going from one place to another.

The mesmerizing work St. Helena Olive Tree, Extinct 1884–1977, 2003–2010 (2011) is based on a tree that was thought to have gone extinct until a single plant was discovered in 1977, only to disappear again in 2010. At the beginning of the 19th century, many photographers were fascinated with the medium’s ability to freeze a slice of time, to isolate and preserve a transitory moment from the flux of life. Before the invention of photography, however, drawings served to classify and identify plants. In this work, a large black-and-white projection captures the play of light and shadow cast by a paper reproduction of the extinct tree modelled from a botanical drawing of it found on the Internet. The paper leaves dance gently in the wind, and a copy of the drawing is appended to the wall. The tree is then doubly reproduced; it’s a model of a replica that still looks uncannily like a living tree. And it evokes the subjectivity that characterizes interpretations of the past.

The St. Helena olive tree seems to have come in and out of being, and the paper sculpture in Soft Turns’ sequence of images is, likewise, a ghostly apparition. Artifice and reality are intermingled as the frozen moments are transformed into a sensual cycle, a painting with light that seems to breathe new life into the extinct plant. Since the shadows created by the model occupy almost half the screen, the olive tree appears to be both tangible and immaterial. Fact and fiction also merge in a soundtrack of crinkling paper, a suggestion of how the plant may have sounded while fluctuating in the wind.

Overall, the works in this exhibition challenge received wisdom about the distance between the artificial and the natural.