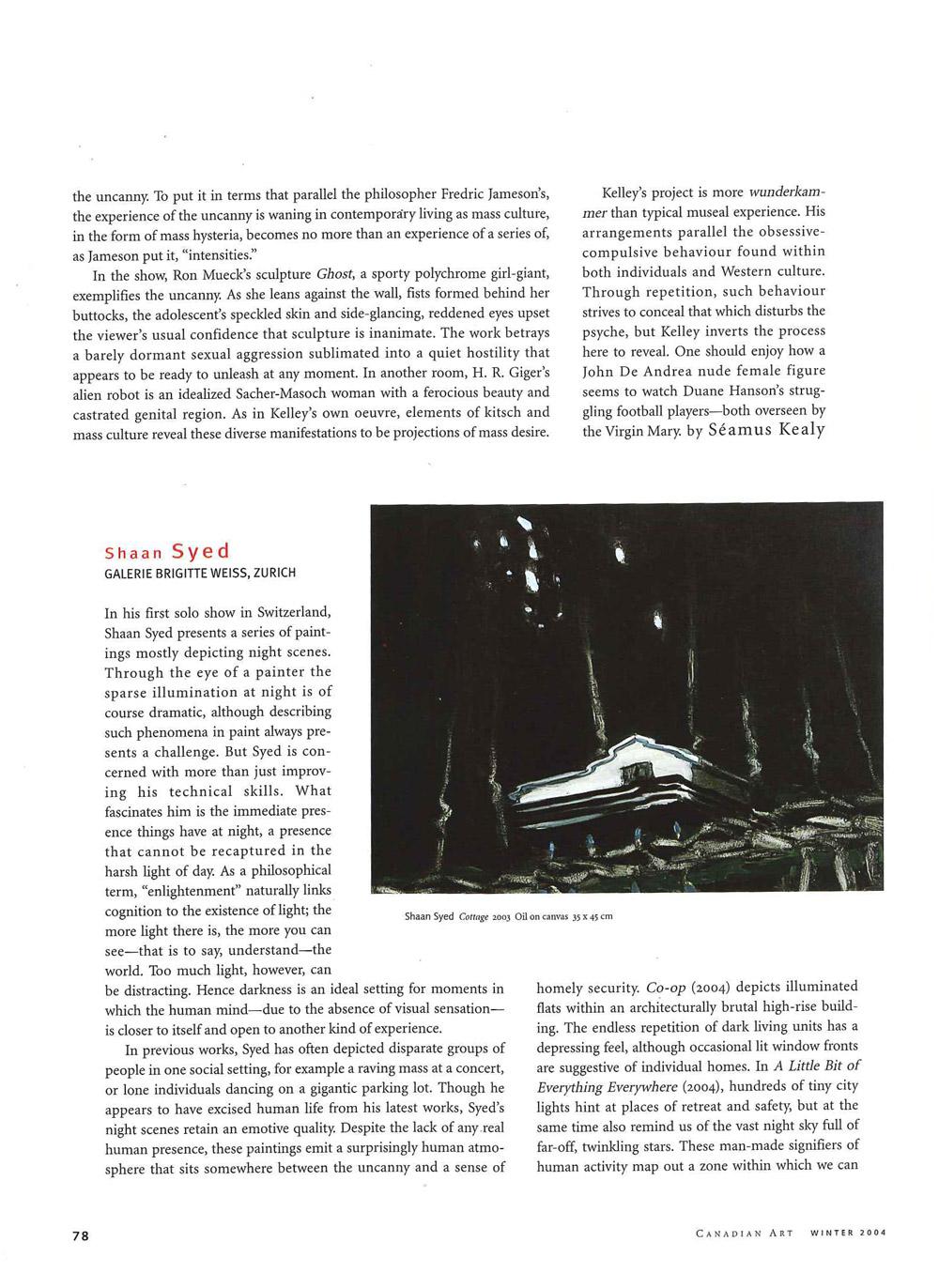

In his first solo show in Switzerland, Shaan Syed presents a series of paintings mostly depicting night scenes. Through the eye of a painter, the sparse illumination at night is of course dramatic, although describing such phenomena in paint always presents a challenge. But Syed is concerned with more than just improving his technical skills. What fascinates him is the immediate presence things have at night, a presence that cannot be recaptured in the harsh light of day. As a philosophical term, “enlightenment” naturally links cognition to the existence of light; the more light there is, the more you can see—that is to say, understand—the world. Too much light, however, can be distracting. Hence darkness is an ideal setting for moments in which the human mind—due to the absence of visual sensation—is closer to itself and open to another kind of experience.

In previous works, Syed has often depicted disparate groups of people in one social setting, for example a raving mass at a concert, or lone individuals dancing on a gigantic parking lot. Though he appears to have excised human life from his latest works, Syed’s night scenes retain an emotive quality. Despite the lack of any real human presence, these paintings emit a surprisingly human atmosphere that sits somewhere between the uncanny and a sense of homely security. Co-op (2004) depicts illuminated flats within an architecturally brutal high-rise building. The endless repetition of dark living units has a depressing feel, although occasional lit window fronts are suggestive of individual homes. In A Little Bit of Everything Everywhere (2004), hundreds of tiny city lights hint at places of retreat and safety, but at the same time also remind us of the vast night sky full of far-off, twinkling stars. These man-made signifiers of human activity map out a zone within which we can experience the sublime, and in such an epic setting they are afforded a touch of the sublime themselves.

When Syed presents social settings and activities they tend to remind us of the flip side of life. Rather than running from loneliness, his isolated and solipsistic figures appear to positively embrace it, as if consolation for the fundamental isolation we experience in life and the futility of existence is to be found in solitude. Deer (2003) and Stag (2004) provide perhaps the best examples of this existential tone. They describe the experience of walking into a forest and being confronted with a wild animal. For a split second, absolute self-confidence takes over and you feel momentarily in unison with the world.

This is a review from the Winter 2004 issue of Canadian Art.