It was immediately apparent, even before entering the recent exhibition “Negative Miracle” at Glasgow Sculpture Studios, that Canadian artist Scott Rogers conspired to enliven or disarm what we might usually (and mistakenly) take as neutral gallery space. A canvas dropcloth covered the entire floor, uniting the exhibition’s sparsely laid objects as if they were part of a room-sized horizontal painting, and I wasn’t sure whether to proceed past the entrance for fear I might be stepping on the art. The artist’s scheme to implicate the viewer in the work (visitors’ footprints inevitably left traces on the canvas) was much more subtle and ambiguous than that of a Gonzalez-Torres piece.

In his earlier 2010 work Wireframe, shown at Calgary’s Stride Gallery, Rogers created a similar provocation that forced the viewer into a pitch-black space delineated with phosphorescent tape. Even while seeming to be Wireframe’s visual opposite, the light, spacious “Negative Miracle” slowed you down. Unsure of your place, like a rabbit crossing a city street, you walked in softer, lighter and more precarious steps.

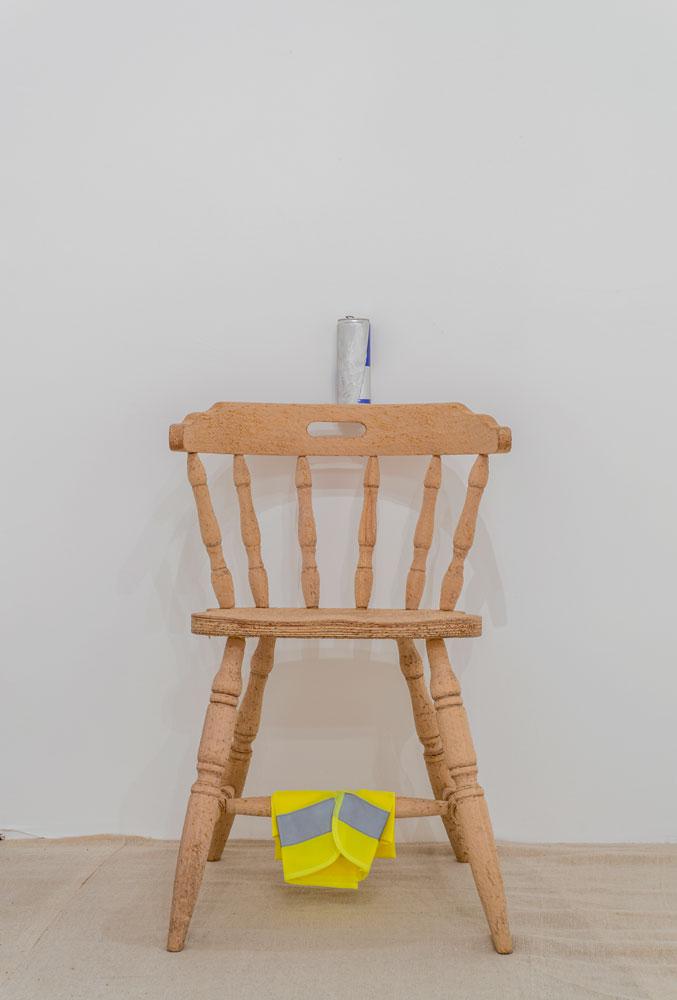

Rogers’s surface alteration of the floor also identified a rift between appearance and actuality—a premise that ran throughout the show—as we knew of, but were unaffected by, the hard, concrete and codified gallery floor underneath the dropcloth. The space felt somewhat romantic and enchanting, if not surreal. Treading on what felt like a soft forest floor, the viewer wound haphazardly through small clusters of dried flowers, bronze-painted ginger root, hand-whittled wood, and rusted metal. Even the objects that one could recognize as coming from an industrial or commercial world of hypersaturated colours—such as high-visibility vests, trendy aluminum water bottles, and cans of Red Bull—were physically stripped of high-chrome sheen, appearing “naturalized” or faded. A kind of nostalgic, sepia-toned atmosphere set in.

The tension set up between appearance and reality was kept in question by a conflation between natural and artificial processes of decay or corrosion. Many of the surfaces of Rogers’s objects had undergone processes of simulated aging, while others had undergone instantaneous transformations, such as a piece of New Brunswick sidewalk concrete that had been shattered apart by lightning. Baudrillard’s counterpoint between “design” and “atmosphere” turned seamless as we slowly realized that this atmosphere of gentle decay and “natural” process was, more often than not, achieved by design.

Take, for instance, the work Like Water in Water (2013), in which four wooden chairs appear to have been carved from a natural, untreated piece of lumber. These are actually readymade chairs whose stain and sealant has been meticulously chipped away by the artist. An accompanying exhibition text asks what differences there are between “artificial” and “anonymous” sources of surface corrosion. Clued in by a wooden massage tool and a rubber hand-trainer sitting on or near the chairs, we guessed that yes, there absolutely are differences—differences at the level of labour and muscle exertion, even if we can’t see them.

We don’t need to turn to the recent philosophical developments of the Speculative Realists, who work against the privileging of man’s knowledge of being, to know that appearances can be deceiving. Like these thinkers, Rogers highlights that everything we think we know is based on accidental appearances that have no correlation to things as they really are. In the case of Pre-Trackers (2013)—resin castings of digital cameras with glow-in-the-dark pigment added in—our assumption of being able to access the “site” of the art was upturned when we discovered the glowing could only be perceived when the gallery was shut down for the day.

A camera which records nothing, and which has “no function other than to act as a reminder of what it once was and what it once did,” alludes to a world that happens outside of human use, and even out of human sight or mind. What function might such a recording device serve when it outlives us?

Two other pieces from the exhibition are also caught up in this question of human apocalypse. The video No Date (2013) chronicles the activities of non-human animals as they tend to their own directives within the city, as if humans weren’t there. Warholian in pace, the video follows a snail’s slow journey, among other phenomena. In the exhibition context, one pondered the intended use and misuse of this image-recording technology, as well as its place in a world without us. An audio piece, which perhaps added to the romantic, bucolic feel, offered a recording of Alexander Scriabin’s unfinished symphony Mysterium (1903–1915), which the late composer hoped would cause a kind of “armageddon” or a somehow-pleasant human apocalypse.

Through this audio piece and its references, the exhibition once again troubled any correlation between thought and reality. It seemed to ask, “Why shouldn’t the apocalypse be pleasant?” Our knowledge of death may be one thing, but there is evidence that death means something infinitely different to other beings. Death can even become a patina or surface element, as the constellation of altered or aged objects in the exhibition suggested. In these, we saw the limits to a “belief in surface,” as a bronze-painted ginger root continued to grow beyond the paint.

If the title “Negative Miracle” referred to a contradiction between intention and artifact, surface and essence, thought and reality, then maybe I should second-guess my first impression of the room’s romantic atmosphere. Then again, it might be with renewed optimism that I now comprehend life, vitalism, lastingness and complexity—beyond the gallery, beyond human sight, beyond human understanding. Like the accidental footsteps I left behind, unintentionally straining and distressing the art, Rogers’s exhibition drew attention to the parenthetical systems of meaning that exist between and beyond the ones we think we know.