The present image of history resides in a wastebasket, a vast garbage heap where photographs, image clippings, wrappers and pixilated screens pile up with no end in sight. As waste, these products are no longer trapped in unbroken, homogenous time, but accumulate and accrue in constellations bursting with contradictions. “UNDERTHESUN,” Roy Arden’s exhibition at the Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG) in Vancouver, dove headlong into the garbage pile and rose to face the blinding noonday sun. In his new pieces, Arden no longer plays the role of photographer, but instead works with and through history’s detritus: he collects, cuts, paints and reassembles photographs, magazine clippings and other images in order to shock history into an electrically charged force field of tension.

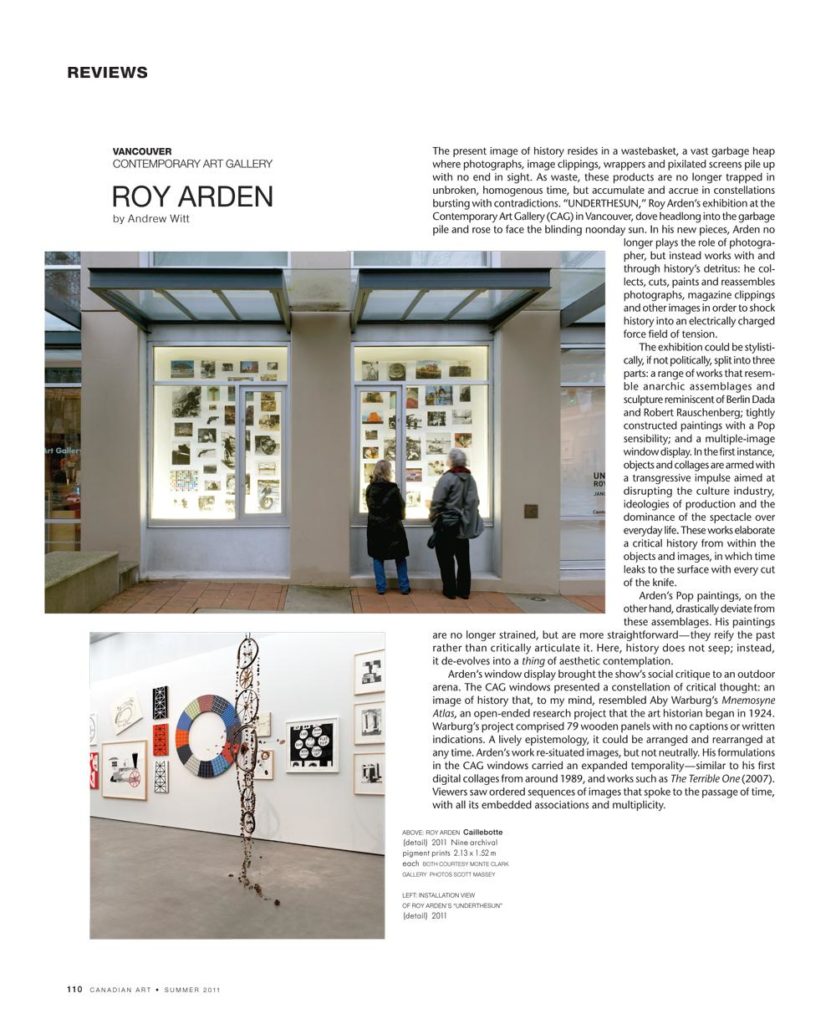

The exhibition could be stylistically, if not politically, split into three parts: a range of works that resemble anarchic assemblages and sculpture reminiscent of Berlin Dada and Robert Rauschenberg; tightly constructed paintings with a Pop sensibility; and a multiple-image window display. In the first instance, objects and collages are armed with a transgressive impulse aimed at disrupting the culture industry, ideologies of production and the dominance of the spectacle over everyday life. These works elaborate a critical history from within the objects and images, in which time leaks to the surface with every cut of the knife.

Arden’s Pop paintings, on the other hand, drastically deviate from these assemblages. His paintings are no longer strained, but are more straightforward—they reify the past rather than critically articulate it. Here, history does not seep; instead, it de-evolves into a thing of aesthetic contemplation.

Arden’s window display brought the show’s social critique to an outdoor arena. The CAG windows presented a constellation of critical thought: an image of history that, to my mind, resembled Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, an open-ended research project that the art historian began in 1924. Warburg’s project comprised 79 wooden panels with no captions or written indications. A lively epistemology, it could be arranged and rearranged at any time. Arden’s work re-situated images, but not neutrally. His formulations in the CAG windows carried an expanded temporality—similar to his first digital collages from around 1989, and works such as The Terrible One (2007). Viewers saw ordered sequences of images that spoke to the passage of time, with all its embedded associations and multiplicity.

This is an article from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art