More than most artists of his age and stature, Rodney Graham has largely avoided branding himself and settling into a repetitive groove of diminishing returns. His prolific, eclectic practice has included painting, sculpture, performance, installation, public art, film, video and photography. However, one area he has returned to frequently in recent years is a kind of ironic self-portrait/self-performance that makes explicit the elements of self-negation, self-concealment and self-invention embedded in any performance or portrait.

This strand first appeared in moving-image works, such as Graham’s video Halcion Sleep (1994) and continued in a glossier vein with his celebrated cinematic loops, including Vexation Island (1997), How I Became a Ramblin’ Man (1999) and City Self/Country Self (2001).

Graham then shifted to a photographic variation on this theme. The C-print diptych Fishing on a Jetty (2000) featured Graham impersonating Cary Grant in a composition based on a scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief. This was followed in 2002 by another diptych self-portrait, Fantasia for Four Hands (2002), in which Graham doubled down on Jeff Wall’s Double Self-Portrait (1979) in a composition inspired by album art from the popular easy-listening piano duo Ferrante and Teicher (with an allusion to Yves Klein thrown in for good measure).

With their idiosyncratic references to art history, cinema and 20th-century culture, as well as their conscious repurposing of Wall’s “cinematography” methods, Fishing… and Fantasia… can be seen as direct precursors to the series of large-scale light box self-portraits Graham has been making off and on since 2005, and which are accumulating into a major body of work. Often presented as diptychs or triptychs, they feature Graham, meticulously costumed but always recognizable, portraying a variety of characters in elaborately staged period-specific scenes.

Graham’s latest exhibition at 303 Gallery in New York featured four recent works in this loose series. The show found the seemingly tireless 64-year-old Graham ruminating playfully on aging, solitude and the unsettling flipside of repose. The press release described the large backlit photographs as a continuation of Graham’s “allegorical self-portraiture.” However, as with the rest of the series, any autobiographical content seemed secondary to the detailed artifice of Graham’s mise en scène. The works attest to Graham’s continuing interest in merging the artist’s studio with the film studio and assuming the role of auteur/star.

Graham’s light boxes, like his film loops, are certainly more accessible than some of his more intellectually ambitious conceptual projects. Indeed, investigating the overlap between “serious” art and “light” entertainment seems to be part of what Graham is up to with these works. With his gift for maintaining a familiar charisma and consistent persona while inhabiting a wide range of characters, Graham’s performance style often recalls that of a classic Hollywood movie star (Cary Grant was an apt choice for impersonation).

Though always amusing, Graham’s anchoring presence can initially make the works feel a bit one-note, like endless variations of an experiment testing his capacity to project affable, deadpan ambivalence through a variety of settings and character types. However, Graham’s performances and compositions reward close consideration and provide a distinct kind of pleasure, which increases in complexity with each new photograph in the series.

Cactus Fan (2013), a single-panel light box on based Carl Spitzweg’s 1850 painting The Cactus Enthusiast, features Graham as a scientist in a laboratory staring at a cactus on the countertop. The muted green of the cactus matches the tones of the fluorescent-lit lab, but the plant pot is wrapped in bright yellow paper and decorated with colourful helium balloons, the festive childishness of which contrasts with the antiseptic setting.

Standing a few steps back from the apparent gift with his arms crossed, Graham’s scientist regards this alien presence of life with an intense but ambivalent gaze signalling perhaps fascination, perhaps consternation. However one reads his expression, characterizing him as a “fan” strikes an amusingly discordant note similar to the irony of Spitzweg’s title in relation to the stooped, bulbous figure in his painting.

Old Punk on Pay Phone (2012), also a single panel, is a study of concealment as character expression. As the old punk, Graham’s face is mostly hidden behind the receiver of the pay phone, but his wide eyes, his alert posture and his wardrobe speak volumes. The combat boots, the wallet chain with oversized safety pin, the eyeliner, the spiked grey hair and the studded black leather jacket all appear as a kind of character armour, at once an aggressive form of self-expression and an elaborate protective disguise. Bright blue and yellow graffiti on the brick wall acts as a vibrant Lichtenstein-esque Pop art backdrop. As with the balloons in Cactus Fan, the youthful blast of colour undermines the carefully constructed identity of the protagonist, making him seem both more ridiculous and more sympathetic.

The Drywaller (2012) is a diptych featuring Graham as the title character taking a smoke break while casually standing on work stilts. The black and red of his plaid shirt in the left panel rhymes with the black space heater bearing glowing orange filaments in the right panel, while an off-white wall marked with a grid pattern and dots stretches across both panels. This faux–Abstract Expressionist backdrop, along with the listless expression worn by Graham’s worker and the incidental vaudeville of his stilts, emphasizes in a darkly humourous manner that this is, decidedly, a portrait of a non-artist as an aging man. As artist/performer, Graham can be both in on the joke and the butt of it at the same time—a move he pulls off in all of these works.

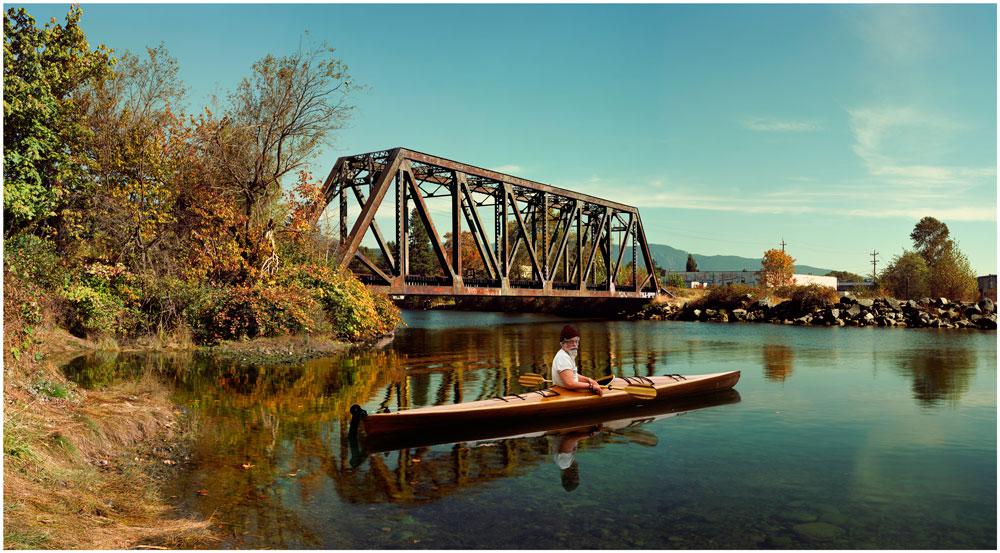

At 18 feet wide, the triptych Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour (2012–13) is the largest work in the exhibition, though the only one with the figure presented at significantly less than human scale. Graham occupies the centre panel as a white-bearded kayaker floating in front of an old bridge. It’s hard to say what the paddler’s odd look signifies, except that it is the opposite of peaceful and content.

The composition is based pretty directly on Thomas Eakins’s 1871 painting The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull), though Graham shifts the blue-dominant tones of the original to a more autumnal register to go along with the increase in age of Eakins’s youthful competitive rower to Graham’s late-middle-aged hobbyist.

Aesthetically, Paddler… was the most complex work in the exhibition. The rich array of greens, browns and oranges provided by the foliage in the left panel are picked up by the rusted bridge and wooden kayak in the centre panel, where they bleed into the reflection of the turquoise water before the pale blue of the sky takes over in the right panel. The hyperreal aesthetic Graham achieves is like a Technicolor reimagining of 19th-century painting—Thomas Eakins meets Douglas Sirk.

Whether Graham’s “allegorical self-portraiture,” in moving or in still imagery, adds up to a fragmentarily revealing self-portrait or a series of sly allegories on the pleasures of perpetual evasion inherent in inhabiting and constructing images is a question that remains open. One might suspect that pursuing variations of this ambiguity over dozens of works would eventually lead to that rut of diminishing returns Graham has thus far avoided. And yet, as 303 Gallery’s exhibition demonstrated, his seemingly limitless reservoir of scenarios and characters continues to command fresh admiration and, perhaps more importantly, continues to entertain.