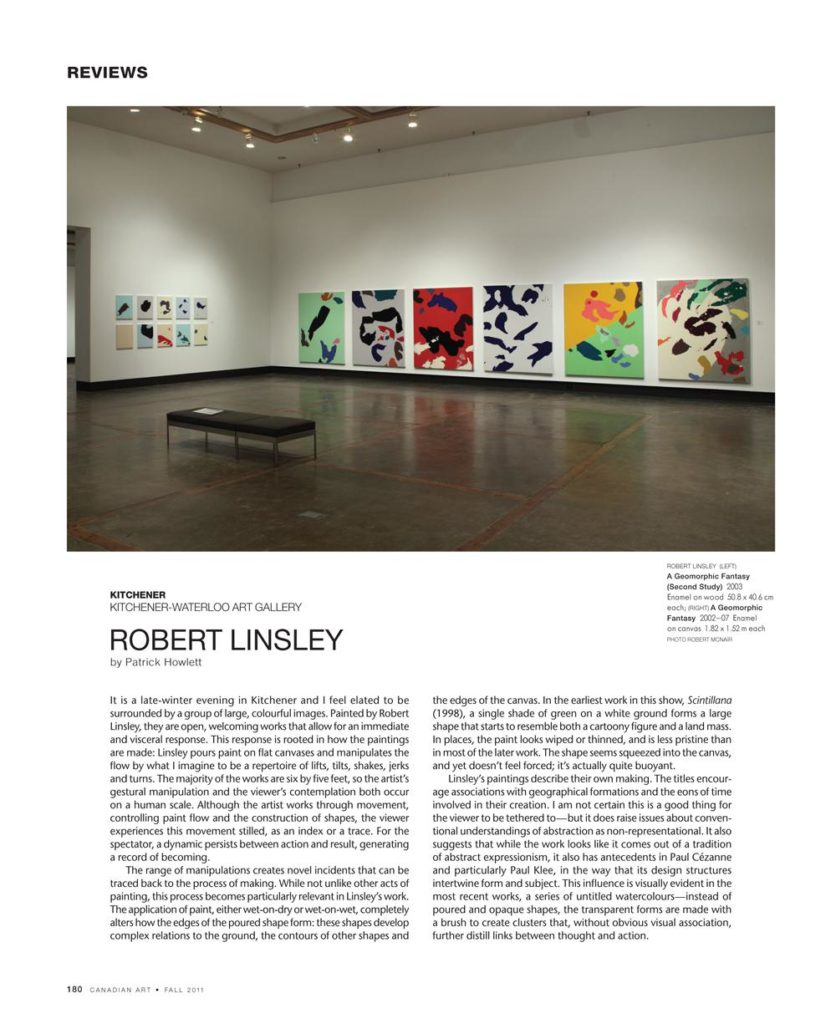

It is a late-winter evening in Kitchener and I feel elated to be surrounded by a group of large, colourful images. Painted by Robert Linsley, they are open, welcoming works that allow for an immediate and visceral response. This response is rooted in how the paintings are made: Linsley pours paint on flat canvases and manipulates the flow by what I imagine to be a repertoire of lifts, tilts, shakes, jerks and turns. The majority of the works are six by five feet, so the artist’s gestural manipulation and the viewer’s contemplation both occur on a human scale. Although the artist works through movement, controlling paint flow and the construction of shapes, the viewer experiences this movement stilled, as an index or a trace. For the spectator, a dynamic persists between action and result, generating a record of becoming.

The range of manipulations creates novel incidents that can be traced back to the process of making. While not unlike other acts of painting, this process becomes particularly relevant in Linsley’s work. The application of paint, either wet-on-dry or wet-on-wet, completely alters how the edges of the poured shape form: these shapes develop complex relations to the ground, the contours of other shapes and the edges of the canvas. In the earliest work in this show, Scintillana (1998), a single shade of green on a white ground forms a large shape that starts to resemble both a cartoony figure and a land mass. In places, the paint looks wiped or thinned, and is less pristine than in most of the later work. The shape seems squeezed into the canvas, and yet doesn’t feel forced; it’s actually quite buoyant.

Linsley’s paintings describe their own making. The titles encourage associations with geographical formations and the eons of time involved in their creation. I am not certain this is a good thing for the viewer to be tethered to—but it does raise issues about conventional understandings of abstraction as non-representational. It also suggests that while the work looks like it comes out of a tradition of abstract expressionism, it also has antecedents in Paul Cézanne and particularly Paul Klee, in the way that its design structures intertwine form and subject. This influence is visually evident in the most recent works, a series of untitled watercolours—instead of poured and opaque shapes, the transparent forms are made with a brush to create clusters that, without obvious visual association, further distill links between thought and action.

This is an article from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

A spread from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art

A spread from the Fall 2011 issue of Canadian Art