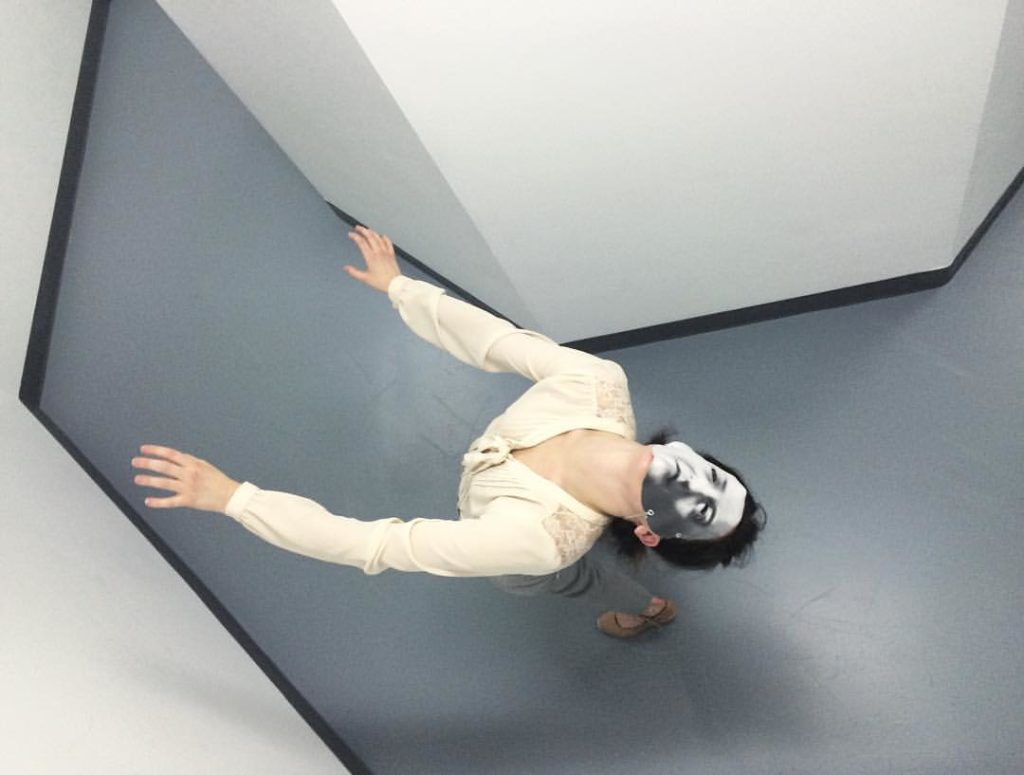

A woman with a mask over her face is walking backwards. The mask is black and white, like a photocopy, like flesh that is no longer alive, like a memory photographed in the 1940s.

But wet, living eyes blink behind the grey skin of the mask, and the arms that reach out from the woman’s torso are yellow-pink, and they tremble as she reaches towards something that her body moves ever further away from. Some parts of her are alive, even if other important parts of her are dead.

It takes great effort for the woman to walk backwards. She is in heels—beige heels—and slim grey slacks, and a proper cream-coloured blouse with a fussy bow. Her hair is in a low bun that unfurls at regular intervals as the woman enacts a series of disturbing gestures. These gestures include running into walls at full force, so that the drywall shakes and trembles; they include twitching, upside down propped against a wall, in a manner that suggests electrocution or seizure; they include curling up into the fetal position, and slowly spinning, slowly spinning, an action that suggests a wish to both ground out, to become solid, and to disappear, to evaporate into air.

Sometimes, the woman tumbles along the grey floor sideways, turning it into a picture plane for those of us standing above on a platform, like doctors in a surgical theatre. This flattening of vigorous human activity against a grey background recalls the absurd (yet revelatory, yet canonical, yet sublime) experiments of Muybridge—black-and-white matrices in which women, sometimes nude, hoisted vases and descended staircases, monochromatic grids in which the mysteries and complexities of the human body were seemingly elucidated, exposed and (at last) understood.

Postpartum depression, by contrast, is something that is difficult for many people to picture, and therefore difficult for many people to understand. This difficulty persists despite the fact that as many as one in six new parents experience it at some point.

Part of what Winnipeg artist Sarah Anne Johnson does in her performance piece Hospital Hallway, recently enacted at Toronto’s Division Gallery as part of the Images Festival and described in part above—as well as in her installation The Kitchen, on view at Gallery 44 until April 23, also via Images—is represent this phenomenon of postpartum depression, and make it visible.

Both Hospital Hallway and The Kitchen are inspired by the life of Johnson’s grandmother, Velma Orlikow, who suffered from postpartum depression in the 1950s.

Yet for me to connect The Kitchen and Hospital Hallway to postpartum depression alone is its own kind of exercise in the flattening and simplification of female experience.

The fact is, Velma Orlikow not only suffered from postpartum depression—a debilitating enough condition in itself. She was also, quite horrifically, abused and traumatized when she attempted to seek help for her condition.

In a scenario worthy of a Margaret Atwood or Philip K. Dick novel—truth is stranger than fiction, always—Orlikow was not, in fact, treated for depression when she entered the care of then-respected psychiatrist Dr. Ewen Cameron in 1956.

Instead, Orlikow unwittingly, and without her consent, became a test subject in a CIA experiment in drug-induced mind control. Yes: a CIA experiment in drug-induced mind control.

Rather than receiving proper drug and talk therapies that could have returned her to herself, and to her family, Orlikow was subjected to methods of so-called “de-patterning” that by the 1980s were revealed to include sleep deprivation (an already existing aspect of early parenthood that has today been strongly correlated to the occurrence and worsening of postpartum depression), multiple doses of daily electroshock therapy (a therapy which can be helpful to some suffering depression, but was mostly likely the opposite when administered in a “de-patterning” regime), and other methods akin to contemporary interrogation techniques.

When this ersatz “treatment” had been completed, and Orlikow was sent home, she could no longer concentrate long enough to read a page of a book. She also suffered, unsurprisingly, from episodes of intense frustration and low mood.

I have experienced postpartum depression and anxiety. The onset came around this time last year, when I found I could not eat and I could not sleep. All I felt was scared. As soon as my baby turned 12 weeks old, my symptoms began. When I would close my eyes, things like dreams would move across my eyelids, though I could also hear whatever else was happening in the house. It was not rest; it was continuation of a nightmare that brought despair and intrusive, destructive thoughts. I sat on the phone with a friend in the dark and I cried as she simply listened. “It’s hard,” she said. “It’s so, so hard.” Her words, wrung from her own experience with this illness, were a lifeline.

Fortunately, the psychiatric, public-health, social and drug supports I received as a white, middle-class, urban woman did, in fact, return me to myself and to my family. For this return, I am grateful, and for this reason, I hesitate to say that I identify even to a certain extent with Johnson’s performances, with her tribute to a grandmother who suffered so much more than me, more than anyone ever should.

However, in Johnson’s video installation The Kitchen, we meet another woman with a mask—this one with the face placed the back of her head—another woman who walks backwards. This woman has to do everything backwards, not just walking. She has to slice bread behind her back, wash dishes, crack eggs, cook spaghetti, make salad and cake, and clean up when, inevitably, she spills it all on the floor and has to start over again.

The woman in The Kitchen wears a prim dress and apron, and heels. Her outfit recalls an earlier era, the 1950s, when expectations of women in North America were even more limiting and circumscribed than they are today. Those expectations are glaringly wrong to most of us now; the expectation that women be beautiful as they labour, be spotless as they scrub, be pleasant even when they are rotting inside.

Yet I doubt that I am the only woman in 2016 who sees her own experience of feeling terribly ill and backward and isolated at least partly mirrored in these screens and scenes. Ultimately, I appreciate Johnson’s efforts here—they are part of a practice that has long been (atypically, in the contemporary-art context) grounded in personal and family experience, and (even more atypically) readable as such. The Kitchen’s exhibition brochure promises more works in future exploring the traumatic narrative that has touched Johnson and her loved ones; I look forward to them.

Leah Sandals is managing editor, online, at Canadian Art.

Sarah Anne Johnson performs in Hospital Hallway at Division Gallery in Toronto. Photo: Stephen Bulger Gallery Facebook Page.

Sarah Anne Johnson performs in Hospital Hallway at Division Gallery in Toronto. Photo: Stephen Bulger Gallery Facebook Page.