In mounting the first Canadian solo exhibition of LA artist Paul Sietsema—who has been a Guggenheim Fellow and received solo exhibitions at MoMA and the Whitney—Mercer Union and the Images Festival have been faced with the challenge of fostering a discussion around works that seem almost impossible to pin down, and that often intentionally explore (mis)communication.

But encountering this difficulty is, overall, worthwhile. The exhibition, humbly titled “Four Works,” serves as an introduction for Canadians to Sietsema’s approach to creation. Its one film and three ink-on-paper pieces offer austere withdrawal from our image-saturated culture, employing slowness, meticulous attention to detail, and repetition to lull viewers into a meditative, reflective state.

Through all four works, Sietsema blends personal history and cultural memory, creating a poetic offshoot of West Coast conceptualism. His approach raises questions about when a single artwork is finished (if ever), and it evokes simultaneous feelings of wonder, unease and dislocation as one material is translated into another seemingly ad infinitum.

***

Sietsema’s 16mm film Telegraph (2012) occupies the main Mercer space. Each of its short sequences displays an array of scrap wood, individual pieces of which disappear through a classic dissolve technique. These dissolves create active, breathing notions of temporality distinct from the jerky start-and-stop sequencing of other kinds of animation; they hint at classic cinematic approaches for transitioning between scenes and times while also evoking the ebb and flow of tides.

Parallel to this visual flux in the film is the alternating obscurity and clarity of its symbolic message. The wooden scraps in each scene form an alphabetical character as part of a larger communiqué, and in viewing the work one wavers between reading each symbol/letter and observing the textured components that create it.

Eventually, however, this Telegraph does relay a message: over its 12-minute duration, it spells out “L/E/T/T/E/R/ T/O/ A/ Y/O/U/N/G/ P/A/I/N/T/E/R,” a reference to Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, which were addressed to an aspiring writer caught between military service and literary ambitions. Sietsema’s “painter” seems a far less specific entity, and his cryptic communication delicately hovers between transmission and breakdown—though the artist has painstakingly relayed a message here, few viewers will likely decipher it.

It’s worth noting that in Sietsema’s practice, the history of materials is never an aside. The wooden fragments in Telegraph have three distinct sources: the remains of buildings damaged during Hurricane Katrina; detritus from Sietsema’s former homes and studios; and objects the artist found by chance in the street. In mixing personal with cultural, and public with private, Sietsema creates an open-ended inter-subjectivity that seems to define his notion of history.

***

In Mercer’s back room are three meticulously hand-rendered works on paper that engage with ideas of materiality and reproduction. Though these often resemble prints in their level of detail, they are in fact ink drawings created by Sietsema by means of what Mercer curator Sarah Robayo Sheridan calls “arcane hand photo-finishing techniques.”

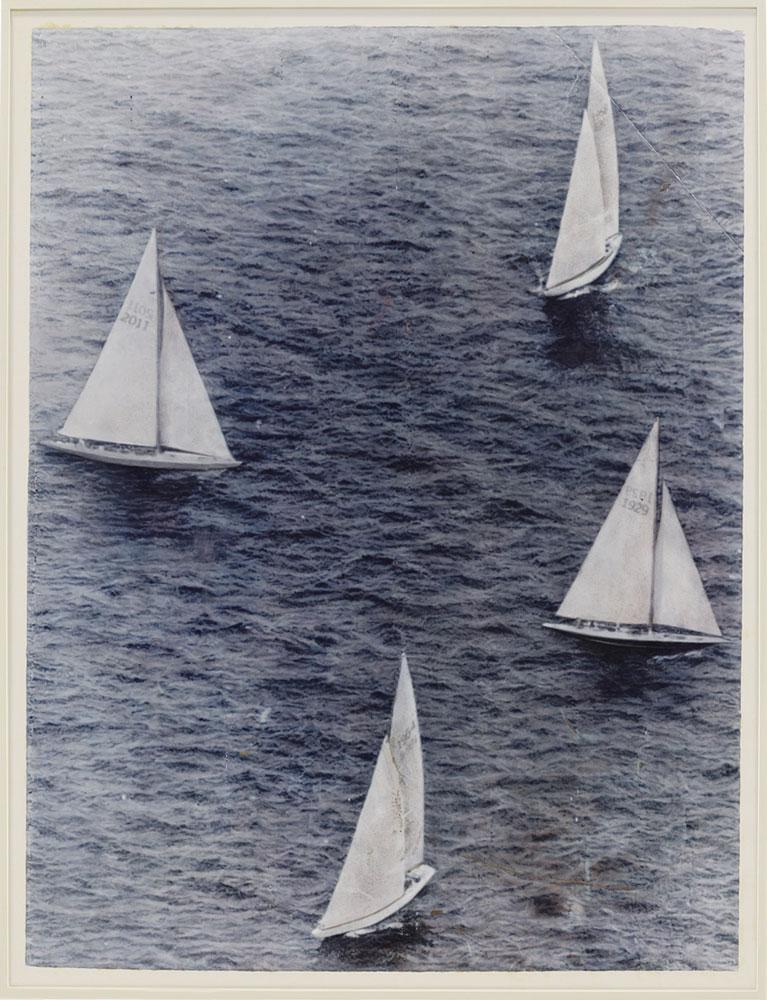

Folded Corner (2012) is a large ink drawing of a photograph of four boats. Like Sietsema’s Calendar Boats (2012)—a series of four nearly identical images a sailboat, based on a single photograph—each boat in Folded Corner is labelled with a year that can be assumed as significant to the artist, a gesture that again generates connections between self-portraiture and socio-cultural histories. The upheavals and conflicts of the past remain present in some way, but are relegated to the placid sea of memory.

Like much of Sietsema’s ink-on-paper work, Folded Corner is equally interested in three things: its direct subject, its own materiality and the materiality of its source artifact. In this case, Sietsema’s attention to the subtle hazing, reverse vignetting and cracked emulsion around the folded corner of the source photograph exude physicality paired with fragility—an effect heightened though its translation of media and scale.

Untitled figure ground study (New York Times) (2009) methodically reproduces a section from the New York Times opened to a review of Sietsema’s 2003 exhibition “Empire” at the Whitney. The just noticeably larger-than-life-sized facsimile’s yellowing pages and dirty, folded corners again bring material concerns to the forefront.

Throughout Sietsema’s Untitled figure ground study series, the newspapers represented—though they may not intersect as directly with his practice—convey a physical immediacy that is heightened by a violent, thickly painted abstraction on the work’s surface. These globby protuberances sitting on top of the newspaper images generate resonances with Abstract Expressionism, yet also call to mind the soiled newspaper refuse of a domestic painting project. As can be seen online, Sietsema has played up this duplicity throughout the series, with some works bearing choreographed formations of rings marks from the bottom of paint cans.

The enormous (approximately two-metre-by-two-and-a-half-metre) piece Light fall 4 (hand to hand) (2012) seems the most enigmatic of the four works at Mercer, though it is conspicuously absent from the accompanying catalogue essay. Like other works in Sietsema’s Light fall series, the source image comes from a 1950s MoMA publication on Abstract Expressionism which includes visitor’s reactions and response-drawings to the then-radical-seeming paintings.

Light fall 4’s hand-rendered replication of the half-tone printing process translates the MoMA catalogue’s small illustrations back to the scale of the Abstract Expressionist artworks they reference—though we never know if these are the catalogue’s reproductions of “official” Ab Ex artworks or simply ones of the “responsive” imitations created by exhibition visitors. The visual connections between the Light fall works and the canvases of Robert Motherwell immediately emphasize the disparity between the vehement ferocity of postwar painters (whose anxieties seem to be signalled through the combative “hand to hand” part of the work’s title) and Sietsema’s reflexively measured gaze.

***

A small aside on hospitality and accessibility: Sietsema’s exhibition, and others like it at Mercer, would be improved with the addition of some benches so that visitors could properly absorb the works on display. “Four Works” is the second Mercer Union show in a row with a single, slow-paced and meditative work in the main exhibition area, but no seating to be found. (The first was Matt Rogalsky’s “Discipline.”) Though it may seem trivial, the simple gesture of providing benches offers comfort to the viewer while making the institutional statement that “we think this work is worth spending time with.” Though I sat on the floor or stood to enjoy these shows, I watched as many other viewers passed by with little engagement, unsure how to interact with the space.

Benches aside, “Four Works” functions well as an introduction to Sietsema’s practice. While an exhibition of this relatively small size cannot convey the repetition and nonlinear seriality that seems plays an important role in Sietsema’s work, Mercer and Images have successfully brought one of Sietsema’s most fascinating qualities into focus: his ability to transcend conversations around originality and appropriation.

Sietsema works not with, but through, source materials, deliberating on their physicality and translating them through media, size and context. This imbues his materials and his works with a complex web of social, cultural, political and personal associations.