When an exhibition focuses on two artists, it often indicates some link between them: for example, because they were collaborators (as in “Pioneering Modern Painting: Cézanne and Pissarro 1865–1885” at the Museum of Modern Art) or because they had shared a source of inspiration (as in “I Had an Interesting French Artist to See Me This Summer: Emily Carr and Wolfgang Paalen in British Columbia” at the Vancouver Art Gallery).

In “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson and Joyce Wieland”—which opened on Canada Day at the McMichael—there is a thematic link, even though these two artists belonged to different generations. Chief curator Sarah Stanners has brought Thomson and Wieland together in order to compose a passionate “love letter” to them while raising questions about gender, myth-making and nationalism in Canadian art.

“The story of Tom Thomson is the male viewpoint, the man in the woods. I’m tired of that,” says curator Stanners in an interview. “So [the exhibition] tells the story through a feminist lens.”

Stanners, who has taught Canadian art, including in-depth study of Joyce Wieland, explains that her intention with “Passion Over Reason” was also “to think not academically but romantically, with imagination. Both artists were so passionate—they lived for their art.”

Tom Thomson, Smoke Lake, 1915. Oil on split panel marouflaged onto plywood, 21.5 x 26.9 cm. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. W.D. Patterson. McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Tom Thomson, Smoke Lake, 1915. Oil on split panel marouflaged onto plywood, 21.5 x 26.9 cm. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. W.D. Patterson. McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

“Passion Over Reason” succeeds in overcoming any skepticism about its unusual premise. Thomson and Wieland lived in very different times and worked in divergent genres and styles. Despite this, Stanners and her exhibition help us understand the strong connection between these two artists—mainly by demonstrating Wieland’s own passion for Thomson’s work.

Moreover, there is much to enjoy in the show. There is a strong showing of Wieland’s art in varied media, including her show-stopping 1968 quilt Reason Over Passion. The presentation of Thomson’s landscape sketches is breathtaking.

Issues of nation and institution are also at stake. The exhibition’s title is a deliberate reversal of Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s famous quip, “Reason over passion”—a comment that Wieland herself reworked, and later gifted back to the Trudeaus. This is a sesquicentennial project which also commemorates the centenary of Thomson’s death. And here, the McMichael—an institution whose collection is based mainly in the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson—is displaying almost all of its holdings of Thomson’s paintings, drawings, photographs and personal objects. (The Wieland artworks are loans from other institutions and collectors, plus one promised gift.)

Speaking with Canadian Art, Stanners said that part of her aim is to consider Wieland’s patriotism and to show Thomson in a new context. The press release for the show underlines this feeling: “Taking cues from…Joyce Wieland, who imbued her vision of Thomson and Canada with…femininity, love and sex, and whose work encourages one to let go of the story of Thomson as a lone man-of-the-woods, ‘Passion Over Reason’ confirms what Wieland pointed to in the 1970s: Thomson is Canada.”

Further, the exhibition considers Thomson as both image-maker and image. On view are a wealth of his beloved paintings, but the aim is also to show how Thomson’s sparsely documented life and mysterious death make him “a blank canvas upon which our nation imagines an icon of pure creativity and connectedness to nature,” as a wall text puts it.

A view of the first room of “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland” at the McMichael, with oil sketches by Thomson at left and large textile works by Wieland at right. Photo: Courtesy the McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

A view of the first room of “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland” at the McMichael, with oil sketches by Thomson at left and large textile works by Wieland at right. Photo: Courtesy the McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

The exhibition’s first room dramatically juxtaposes works by Thomson and Wieland on facing walls. On the left-hand wall, 55 Thomson oil sketches float, forming a wing-like shape. Each one shows an effort to record a particular place and time. On the right-hand wall is Wieland’s large quilt Reason Over Passion.

Stanners finds commonalities here and elsewhere in the lives of Thomson and Wieland. “Both…spent time working in the United States…and returned to Canada with a driving impulse to capture the spirit of their country through their art,” says a wall text.

Tom Thomson (1877–1917) grew up in Leith, Ontario, near Owen Sound. He worked as a commercial artist in Seattle and Toronto. In 1912, he made his first visit to Algonquin Park; inspired by the landscape, he arranged his life so that he spent most of each year there, earning money as a guide and forest ranger. He returned to Toronto during the winter months to work in his studio.

Joyce Wieland (1931–1998) was born in Toronto; her parents were immigrants from Britain. Like Thomson, she worked for a time as a commercial artist. Her quilt Reason Over Passion is a large work, over three metres wide, which plays with and subverts language. Each three-dimensional letter in the motto has a contrasting border colour and backing colour, giving it a vivid effect. Yet the many colourful hearts scattered all over the work, some three-dimensional and others flat, disrupt Trudeau’s motto, bringing passion to the fore.

Also on the theme of nation and nationalism, Wieland’s 1969 film Reason Over Passion is shown on continuous loop within the exhibition space. The film celebrates the Canadian landscape as it flowed past her camera during a cross-country journey.

Thomson and the Group of Seven inspired Wieland to undertake this film project. In a 1974 interview about the film, she recalled, “I was thinking about the Group of Seven and that certain artistic records have to be made at certain times. Just look what has happened to many of the places they sketched. There are old shoes and hamburger buns in those lakes…. I photographed the whole length of southern Canada to preserve it in my own way.”

Joyce Wieland, Entrance to Nature, 1988. Canvas collage with oil, glitter, wire, cardboard, staples and metal push pins, 193 × 226.1 cm. Collection of Susan Rynard and Mark Bell. Photo: Cheryl O’Brian, courtesy of Paul Petro Contemporary Art. © National Gallery of Canada.

Joyce Wieland, Entrance to Nature, 1988. Canvas collage with oil, glitter, wire, cardboard, staples and metal push pins, 193 × 226.1 cm. Collection of Susan Rynard and Mark Bell. Photo: Cheryl O’Brian, courtesy of Paul Petro Contemporary Art. © National Gallery of Canada.

The second room of the exhibition focuses on Wieland, particularly her “True Patriot Love” exhibition of 1971—the National Gallery of Canada`s first major solo exhibition of a living Canadian woman artist. The exhibition marked Wieland’s return to Canada after residing in New York City with her husband, artist Michael Snow, for nine years.

As Stanners points out in an interview, “Wieland loved Canada and thought critically about Canada.” The 1970 October Crisis, ecology, feminism and countercultures all affected her art. In her 1967 assemblage Patriotism, forms are encased in a cross, made of shiny plastic. The Canadian flag (then only two years old) is split in two, and partly inverted.

Exploring such Canadian icons led Wieland to a examine Thomson’s image and legacy. In her bookwork for the “True Patriot Love” exhibition, she collaged photographs taken by Thomson himself. She also included, as a wall text indicates, “fragments of a film script Wieland was developing about…Thomson, which sowed the seeds for her 1976 feature-length film, The Far Shore.”

Roughly a decade after The Far Shore, in her large collaged painting Entrance to Nature, Wieland included a red canoe stretching across the base of the composition, in the midst of abstracted flowers and birds. Here, she evokes the unseen presence of Thomson as a guide, artist and protagonist.

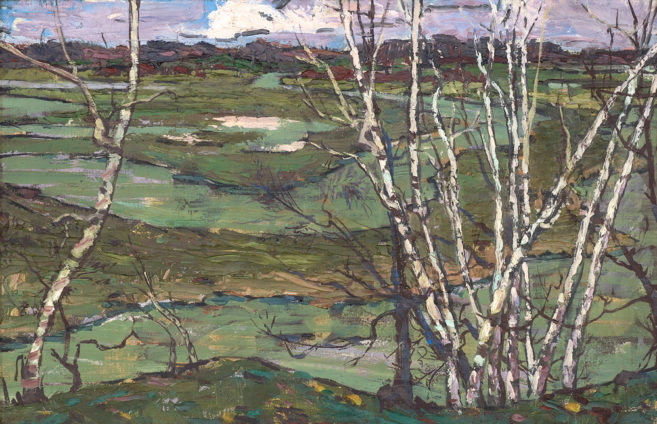

Tom Thomson, Summer Day, 1915. Oil on board, 21.6 x 26.8 cm. Gift of Mr. R.A. Laidlaw. McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Tom Thomson, Summer Day, 1915. Oil on board, 21.6 x 26.8 cm. Gift of Mr. R.A. Laidlaw. McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

The third room of the exhibition has works by both Wieland and Thomson, mainly related to the film The Far Shore. The entire film is available for visitors to watch on demand, and two excerpts run on continuous loop in the exhibition. This was Wieland’s “first and only feature-length, traditional movie” notes the exhibition prospectus; she co-wrote, co-produced and directed it.

The film’s main character, Eulalie, is a young Québecoise who grows dissatisfied with her marriage to a Toronto engineer. “Eulalie falls in love with a woodsman painter named Tom, and they begin an affair which drives them to escape to the…North Country together by canoe,” says a text. In a story that blends love with social criticism, the fictionalized Tom takes a stance against mineral exploration: “Leave the land alone,” he firmly states. Tom is shown not as a lone woodsman figure, but as the perfect romantic partner for Eulalie: sensitive, gentle and free thinking.

This room includes a striking display of “far shore”–style landscapes by Thomson; Stanners chose them because each one is composed of water and a far shore. The panels are of varied dates from 1912 to 1916 and represent different seasons, weather conditions and times of day. As with the Thomson sketches in the first room, the artist’s bold colour and versatility make a strong impression.

A view of the fourth room of “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland,” including, at left Wieland’s 1961 work Heart-On. Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

A view of the fourth room of “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland,” including, at left Wieland’s 1961 work Heart-On. Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

The fourth and last room is somewhat diffuse in theme, as it concerns the artists’ depiction of the natural world, as well as eroticism, queerness and Indigenous perspectives.

Wieland’s 1973 lithograph The Arctic Belongs to Itself asserts her belief that “land and water are best cared for by its indigenous peoples,” according to a wall text. To produce this work, Wieland mouthed the title words while pressing her lips to a lithographic stone, insisting on a personal and physical relationship to language.

On a similar theme, the exhibition displays Wieland’s 1971 embroidered patch White Snow Goose of Canada. This badge’s motto, “Protect Creatures,” appears beside a 1974 Inuit felt and embroidery wall hanging from Baker Lake. The latter, attributed to Hannah (Qillulaaq) Killulark, portrays a multitude of Arctic creatures.

The exhibition’s reference to Indigenous viewpoints here is partially successful, but leaves some questions unanswered. The Wieland and the Killulark make a striking pairing, as both works depict Arctic fauna while employing circles as a design theme. But to clarify the relationship, a more informative label would have been helpful. In addition, it would have been good to include biographical information about Killulark, an accomplished artist and teacher.

Interestingly, the exhibition seems less concerned with showing Indigenous perspectives in relation to Thomson. Perhaps it might have been possible to do this—for example, through a discussion of Indigenous history and presence in the places Thomson painted.

A view of the final room of “Passion Over Reason,” featuring an iconic photo of Tom Thomson at left and a large wall work by contemporary queer artist Zachari Logan at right; the latter is titled Witness, the Near Shore from Eunuch Tapestries (for Tom). Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

A view of the final room of “Passion Over Reason,” featuring an iconic photo of Tom Thomson at left and a large wall work by contemporary queer artist Zachari Logan at right; the latter is titled Witness, the Near Shore from Eunuch Tapestries (for Tom). Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

A small alcove in this last room encloses works by Wieland dealing with sexuality. The major work here is 1961’s Heart-On. Here, Wieland plays with the meaning of colour-field painting, giving the work a feminist twist. The pink-stained canvas suggests menstrual blood, which may have shocked its early 1960s audiences.

Near the conclusion of the exhibition is a suggestion of how our understandings of sexuality affect landscape art—this intervention takes the form of a major work in pastel on black paper, Witness, the Near Shore from Eunuch Tapestries (for Tom), by artist Zachari Logan.

Logan created this piece recently, and also worked in late June and early July in Tom Thomson’s shack on the McMichael’s grounds. A wall text suggests that Logan’s “sense of marginality as a gay man” leads him to “be inspired by the weeds and wild plants…along the margins…such as ditches and shorelines.” Although this is only one corner of the exhibition, Stanners does a fine job of interpreting Logan’s individual point of view as a queer artist.

Zachari Logan discusses his work Pool, for Tom (July 8th 1917, a Wildflower was pulled from Canoe Lake) with chief curator Sarah Stanners at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection grounds. Logan was in residence at Tom Thomson’s cabin on the grounds in late June and early July 2017. Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Zachari Logan discusses his work Pool, for Tom (July 8th 1917, a Wildflower was pulled from Canoe Lake) with chief curator Sarah Stanners at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection grounds. Logan was in residence at Tom Thomson’s cabin on the grounds in late June and early July 2017. Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Overall, no serious flaws mar “Passion Over Reason,” but there are two areas that could have been improved: Three canvases by Thomson, which appeared to be representative of his more finished studio compositions, hang at the end of the exhibition. The lack of a wall text means that the three works seem in limbo, lacking a context. Another problem is the installation and lighting of Logan’s Witness, the Near Shore from Eunuch Tapestries (for Tom). A low light level is required to protect the work, but I would suggest that a different spatial arrangement would have helped visitors adjust their eyes and see this work at its best.

The McMichael is well-known for its strong collection of our so-called “national school,” that is, Thomson and the (all-male) Group of Seven. And Stanners is to be applauded by trying to complicate the narrative with this challenging show. As a wall text states, “The eras in which [Thomson and Wieland’s] artistic practices developed could hardly be more different, and yet this…pairing demonstrates how the past informs the present, and how contemporary art…critiques our sense of art history.”

Wieland spoke nationalism overtly, making use of instantly recognized symbols such as the Canadian flag and anthem. One the other hand, Thomson was not overtly nationalistic in his work—but one might say that his nationalism was implied through his choice of the Northern landscape as subject. And his work has certainly been taken up as nationalistic in the decades since his death.

“Passion Over Reason” may make people more aware of Wieland, while at the same time providing a generous sample of the audience favourite, Thomson.

Allison MacDuffee is a Toronto art historian and freelance writer. She teaches art history at Sheridan College.

Joyce Wieland, Patriotism, 1967. Vinyl, textile, photograph, printed paper, cotton batting, wood, thread, 81.7 × 39.6 cm. Gift of Donna Montague Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery. © National Gallery of Canada.

Joyce Wieland, Patriotism, 1967. Vinyl, textile, photograph, printed paper, cotton batting, wood, thread, 81.7 × 39.6 cm. Gift of Donna Montague Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery. © National Gallery of Canada.

McMichael chief curator Sarah Stanners (centre, in orange) discusses “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland” with Lieutenant Governor Elizabeth Dowdeswell and McMichael CEO Ian Dejardin. Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

McMichael chief curator Sarah Stanners (centre, in orange) discusses “Passion Over Reason: Tom Thomson & Joyce Wieland” with Lieutenant Governor Elizabeth Dowdeswell and McMichael CEO Ian Dejardin. Photo: Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection.