Last Thursday, August 3, was Ribfest at Ottawa City Hall. A semicircle of food trucks occupied the building’s forecourt, stainless-steel rigs belching barbecue smoke. Anti-pork activists occupied the sidewalk. A troupe of bagpipers practiced in the park.

In the Karsh-Masson Gallery, just off the city hall’s atrium, painter Kizi Spielmann Rose was installing “Pulse,” his MFA thesis exhibition, which runs until August 15. When I arrived, the gallery was half-lit. Meaghan Haughian, the gallery coordinator, adjusted spotlights in the ceiling. Spielmann Rose was deep into a conversation with his thesis supervisor, Penny Cousineau-Levine, on the placement of his works. The paintings, small abstract panels bearing undulating fields of vibrant colour, leaned against the wall at their feet.

Kizi Spielmann Rose, Double Up, 2017. Oil pastel and oil on panel, 24 x 30 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Kizi Spielmann Rose, Double Up, 2017. Oil pastel and oil on panel, 24 x 30 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Spielmann Rose works by layering oil pastel and oil stick in freewheeling, biomorphic designs. He then etches hundreds of long, serpentine lines side-by-side into the layers, partially unveiling the hidden forms beneath.

The results are strikingly illusionistic. They evoke shimmering waves, topographical maps, laundry fluttering in the breeze—yet they are linked to a lineage of earnest abstraction. The Op-artists Julian Stanczak and Bridget Riley are among Spielmann Rose’s influences, as is the maximalism of 90s-era Frank Stella.

After the paintings were hung, Spielmann Rose had to make it back to where he lives in Hull, a neighbourhood in Gatineau on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River, to model for a portrait bust.

During the short, un-scenic drive, he mused on the connections between theory and the studio. We talked about the RBC Canadian Painting Competition (he is one of this year’s 15 finalists), and the art world’s reliance on corporate patronage. As we pulled into the drive of the portrait sculptor’s studio—right across from St-Hubert, Hull’s premier destination for chicken and gravy—Spielmann Rose was telling a joke about Kandinsky.

Exterior evening view of AXENÉO7’s main gallery featuring Justin Wonnacott’s exhibition “Images d’art/Pictures of art.” Photo: Jonathan Loranger.

Exterior evening view of AXENÉO7’s main gallery featuring Justin Wonnacott’s exhibition “Images d’art/Pictures of art.” Photo: Jonathan Loranger.

I’d been on the west side of Hull the previous evening, to meet Stefan St-Laurent, the director of the artist-run centre AXENÉO7. The centre’s off-site summer exhibition, “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape”—more on this in a moment—is up until August 30.

“À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” overlaps with “INTERSTICES,” an urban sound art itinerary by the artist-run centre DAÏMÔN. When I arrived at AXENÉO7, around 8:30 p.m., St-Laurent was by the door, Stella Artois in one hand, cigarette in the other.

Justin Wonnacott, Public Art, Christopher Keene, The Hunt (detail), 1986, shot in 2013. An excerpt from the series “Images d’art/Pictures of art.”

Justin Wonnacott, Public Art, Christopher Keene, The Hunt (detail), 1986, shot in 2013. An excerpt from the series “Images d’art/Pictures of art.”

Our first stop was “Pictures of Art,” an exhibition of photographs by Justin Wonnacott in AXENÉO7’s main galleries. The images are deadpan: documentary-style photographs of public art in the Ottawa area. Subjects range from well-meaning-but-ugly community sculptures to one-percent works commissioned for corporate offices. There are public servants eating lunch on national monuments and spray-painted throw-ups by local taggers.

Wonnacott, whose studio is at AXENÉO7, has been working on this series for 16 years. He’s produced close to 400 images so far. “He’ll do it till he dies,” St-Laurent told me. There’s something arresting in “Pictures of Art”: a critical eye behind the lens. As the artist writes in his catalogue statement, “Sometimes my images flatter the art and sometimes not. It is not a democratic selection at all.”

Alexandre David, Field, 2017. Installation viewe at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo: Justin Wonnacott/AXENÉO7.

Alexandre David, Field, 2017. Installation viewe at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo: Justin Wonnacott/AXENÉO7.

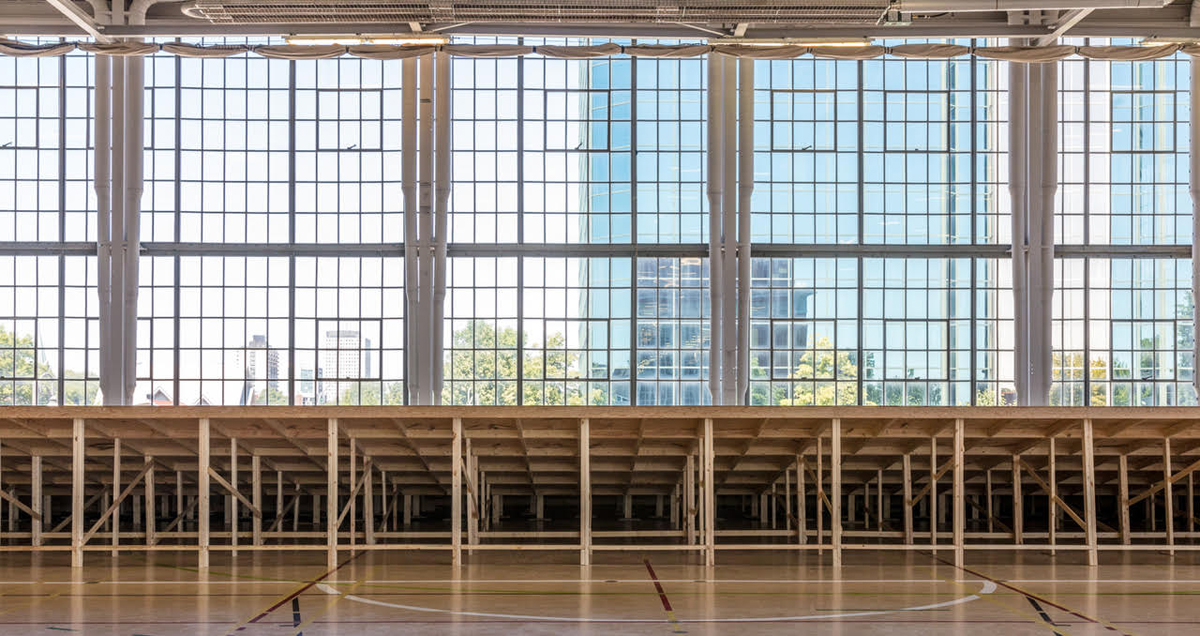

“À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” is a landmark exhibition for AXENÉO7, St-Laurent explained as we left the gallery, walked through a scruffy lot, down a mud slope, over a train track and hopped a traffic barrier. He was showing me the shortcut to La Fonderie, where the bulk of the exhibition is installed. It’s the first time the 58,000-square-foot industrial structure—built a century ago as an iron and steel foundry, now home to a multisport complex—has ever formally shown art.

To begin, the ground floor has been overtaken by aliens. Dominique Pétrin’s comic-apocalyptic mural, UFO Canada, made by gluing silk-screened images to the wall, fills the room with a hallucinatory colonial allegory. Extraterrestrials have discovered the wreckage of present-day Canada. They unearth stale donuts and Tim Hortons coffee cups, OxyContin and Canadian Tire money. Are these the vestiges of some kind of sick cult?

Dominique Pétrin, UFO Canada, 2017. Installation view in “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo: Justin Wonnacott/AXENÉO7.

Dominique Pétrin, UFO Canada, 2017. Installation view in “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo: Justin Wonnacott/AXENÉO7.

Upstairs, in the building’s sweltering main hall, the father-and-sons trio Jim, Nathan and Cedric Bomford have constructed a “cooling tower” on the basketball courts. By the north-facing windows, Alexandre David has built a plywood platform that is perfect for sunbathing.

On the centre’s two indoor soccer fields, artists Graeme Patterson, Samuel Roy-Bois and Michel de Broin each conceived of large-scale installations. “There was no way we were going to cover up this AstroTurf,” St-Laurent told me, so the artists adapted to their sportif surroundings.

Installation view at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo credit: Jonathan Lorange/AXENÉO7.

Installation view at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo credit: Jonathan Lorange/AXENÉO7.

For MAKE SOCCER GREAT AGAIN, De Broin overlaid the white markings on the central field with knee-high picket fences, segregating the players and restricting ball movement. (St-Laurent said visitors have been inventing new sports here.)

For Tout est fragile/Le perchis, Roy-Bois built a “Prismacolor forest” out of painted two-by-fours, which are decorated with found objects (including, apparently, a rotting loaf of bread). And for Infinity Pool, Patterson engineered a micro-suburban ecosystem, complete with backyard pools and automated birds that defecate into them.

“The tourist class that come visit, they’re really quite shocked,” St-Laurent said, as we walked downstairs into the cool night air.

We crossed the parking lot (which fills during the day with the haunting sounds of Sonia Paço-Rocchia’s 04v01) and turned around to look at Thunderbird Watches the River. Make an Offering and Take Water into the Palm of Your Hand, by Nadia Myre and the Ogimaa Mikana Project (a collective dedicated to restoring Anishinaabemowin place-names in Canadian cities).

Nadia Myre with the Ogimaa Mikana Project (Hayden King & Susan Blight),Thunderbird Watches the River. Make an Offering and Take Water into the Palm of Your Hand, 2017. Installation view at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo: Jonathan Lorange/AXENÉO7.

Nadia Myre with the Ogimaa Mikana Project (Hayden King & Susan Blight),Thunderbird Watches the River. Make an Offering and Take Water into the Palm of Your Hand, 2017. Installation view at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape” in La Fonderie, Gatineau. Photo: Jonathan Lorange/AXENÉO7.

Across thousands of illuminated panes, the words “KI DA NISH KWASSE” (translation: “The end is coming”) spanned the building’s eastern face. Like Pétrin’s alien invasion or Patterson’s suburban dystopia, it read as a warning—of the dangers of consumerism, suburban sprawl, social engineering. But it was also a message of hope: the end, perhaps, of environmental degradation. Or the long-awaited end of colonization.

Back at AXENÉO7, St-Laurent and I walked along the Ruisseau de la Brasserie. From behind, a drunk cyclist almost crashed into us. As he careened into the night, muttering his apologies, St-Laurent laughed. “That’s very Hull.”

Graeme Patterson, Piscine infinie / Infinity Pool, 2017. Installation view at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape.” in La Fonderie, Gatineau Photo: Jonathan Lorange/AXENÉO7.

Graeme Patterson, Piscine infinie / Infinity Pool, 2017. Installation view at “À perte de vue/Endless Landscape.” in La Fonderie, Gatineau Photo: Jonathan Lorange/AXENÉO7.