Remedy (2017) by Anna Williams consists of bronzes of plants and herbs used to treat “depression and female disorders,” says the artist. It was part of “Beneath the Tame” at Gallery 101 in Ottawa. Photo: David Barbour.

Remedy (2017) by Anna Williams consists of bronzes of plants and herbs used to treat “depression and female disorders,” says the artist. It was part of “Beneath the Tame” at Gallery 101 in Ottawa. Photo: David Barbour.

Tucked away in an industrial building beside the Queensway is Gallery 101, whose most recent exhibition, “Beneath The Tame,” commanded attention. It was the final exhibition at the gallery’s Young Street location, which is due to be demolished soon by the Ontario Ministry of Transportation—and the show boded well for next year’s programming at a new Catherine Street space.

“Beneath The Tame” featured sculpture and installation from Mary Anne Barkhouse (based in Minden and a member of Kwakiutl First Nation) and from Anna Williams (based in Ottawa), with the works stretching abundantly from wall to wall and floor to ceiling.

Throughout, works depicting birds, wolves, dogs, plants and the human form explored the space between the wild and the tame, “hover[ing] over the animal image as entwined in the human imaginary,” wrote curator Lisa Pai.

Red Rover (2017), Barkhouse’s large pink and black installation on the floor by the gallery entrance, features poodles and wolves at a standoff. Here, domesticated and wild animals are arranged on a map of the controversial Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Pipeline, running from Alberta to western British Columbia. The pink poodles were situated on the east side of the map, the black wolves to the west.

Mary Anne Barkhouse’s installation Red Rover (in foreground) has pink poodles face off against black wolves on a map of the proposed Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Pipeline extension. The work was part of “Beneath the Tame” at Gallery 101 in Ottawa. Photo: David Barbour.

Mary Anne Barkhouse’s installation Red Rover (in foreground) has pink poodles face off against black wolves on a map of the proposed Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Pipeline extension. The work was part of “Beneath the Tame” at Gallery 101 in Ottawa. Photo: David Barbour.

Bronze sculptures of women and wolves by Anna Williams led towards a bright red wall upon which were hung bronzes of herbs used to treat “depression and female disorders.” These latter sculptures, titled Remedy (2017), are about “trying to offer strength and resilience to the natural world,” Williams tells me. The layout also emphasizes, she says, “my female experience as it is pushed into a structured grid and a medicalized existence created by men, [a structure] in which we have being forced to confine our womanhood.”

Also building on these themes is Williams’s bronze Leda and the Swan (2017), referring to the Greek myth wherein Zeus, in the form of a swan, seduces (or rapes, depending on the interpretation) Leda, the wife of the king of Sparta. In the artist’s version, Leda stands tall, holding an axe over her shoulder, with the swan/Zeus subdued, captured and dragged beside her.

Anna Williams, Leda and the Swan, 2017. Installation view. Cast bronze, cast resin, paint, antique axe, reclaimed wood, 5’ x 2’ x 2’. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Anna Williams, Leda and the Swan, 2017. Installation view. Cast bronze, cast resin, paint, antique axe, reclaimed wood, 5’ x 2’ x 2’. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

Overall, “Beneath the Tame” found and held a delicate balance, filling much of the gallery without overwhelming the viewer. Several themes were explored, including feminism and environmentalism, while fitting within the context of the show.

More broadly, “Beneath The Tame” highlighted a sense of tension, of conflict bubbling underneath a surface. These surfaces are also architectural and geographical—after speaking with the gallery’s director Laura Margita, I was led outside to the rooftop to see Mary Anne Barkhouse’s 99.96% (2017), which shows a poodle and a wolf facing off once more over their territory, despite (or perhaps because of) the 99.96% genetic similarities they share.

An installation view of a shared room at Jillian McDonald and Manon Labrosse’s exhibition at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

An installation view of a shared room at Jillian McDonald and Manon Labrosse’s exhibition at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Artwork by two other women, Manon Labrosse and Jillian McDonald, can be found across the river in Hull at the artist-run Axenéo7. Here, paintings, photographs and videos informed by humanity’s impact on nature span several rooms.

Labrosse, originally from Northern Ontario and based in rural Quebec, spins off of scenes of nature in her semi-abstract series How to Paint Death According to Lucy/Comment peindre la mort d’àpres Lucie (2017). Her works range vastly in size, but all surface a variety of bright green, pink and orange hues.

In one room, a large multi-panelled work by Labrosse fills a wall, effectively recreating a passage through the forest, complete with branches, roots and fallen foliage.

In another room, smaller works are installed above wallpaper that was designed by the artist specifically for the exhibition.

The inspiration for her work, Labrosse says, comes from in part from the short story “Death by Landscape” by Margaret Atwood. From this, Labrosse extrapolates a different world, one where nature has been allowed to dominate.

Manon Labrosse’s large painting How to Paint Death According to Lucy/Comment peindre la mort d’àpres Lucie (2017). Installation view at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Manon Labrosse’s large painting How to Paint Death According to Lucy/Comment peindre la mort d’àpres Lucie (2017). Installation view at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Jillian McDonald is based in Brooklyn, and originally hails from Winnipeg. Her Crystal Lake (2017), which is premiering at Axenéo7, involves video work, still photographs and drawings.

Shot on the eastern side of Georgian Bay, the video and still photographs of Crystal Lake portray landscapes altered in post-production. McDonald uses the addition of supernatural effects and image mirroring to create otherworldly and symmetrical imagery that seems familiar but also eerie—the artist has removed of all signs of human impact (cottages, boats and figures) from her scenes.

While the omission of the overtly human results in landscapes that are in a (well, arguably) more natural state, McDonald’s digital reworking is also fantastical and unnatural in its effects. The music accompanying Crystal Lake, reworked from natural soundscapes at the location, increases the sense of a whimsical ambience.

Directly across from the video, too, is an installation of bird drawings appropriated from Audubon’s famous Birds of North America and inspired by Hitchcock’s The Birds—a nod to the artist’s appreciation of horror films and other uncanny sources.

Jillian McDonald’s Crystal Lake (2017) consists of eerie photographs, videos and soundscapes. Installation view at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Jillian McDonald’s Crystal Lake (2017) consists of eerie photographs, videos and soundscapes. Installation view at Axenéo7. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

In terms of curation, the placement of Labrosse and McDonald’s work at Axenéo7 finds each artist with a room to themselves and a room shared; each has work installed in various ways, from a salon or stacked style of hanging (as with Labrosse’s “mini” paintings and McDonald’s birds) to a more minimalist install (as with Labrosse’s large-scale work and McDonald’s photo stills). Both artists represent the natural landscape and its relationship with humanity with intriguing, and differentiated, contemporary visions resulting in two exhibitions that manage to interact and complement each other well.

Back across the bridge, the Canadian Photography Institute (CPI), located inside the National Gallery of Canada, opened three new exhibitions in early November centred around themes of “borders, territory and migration.” Curated by Luce Lebart, the director of the CPI, the exhibitions explore the California-to-Yukon gold rush of the 19th century, the border between the United States and Mexico, and the border between the US and Canada.

Greeting visitors on the left when entering the institute is “Gold and Silver: Images and Illusions of the Gold Rush,” largely featuring daguerreotypes from the 1800s. Portraits of miners and images of landscape fill the space alongside objects and artifacts: gold nuggets, stock certificates, early maps and propaganda posters. The atmosphere of the time is brought out through the inclusion of these objects with pinpoint lighting and clever exhibition design throughout the rooms, and the exhibition also provides examples of some of the first publicly available forms of photography.

Asahel Curtis, Horse drawn sleds nearing custom house, vicinity of Summit Lake, ca. 1898. Gelatin-silver print, 4 ½ x 8 in. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

Asahel Curtis, Horse drawn sleds nearing custom house, vicinity of Summit Lake, ca. 1898. Gelatin-silver print, 4 ½ x 8 in. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

To the right of the entrance of the CPI galleries is its PhotoLab, an “experimental” space for photo-based exhibitions. This iteration, “PhotoLab3: Between Friends,” features Andreas Rutkauskas’s photographs covering the border between the United States and Canada. The title “Between Friends” borrows from a book of the same name gifted by Canada to the US to celebrate the American bicentennial in 1976.

The artist photographed the US-Canada border area starting in 2012, he says, to show what had already changed, but also what hadn’t: though it’s touted as the world’s “largest undefended border,” Rutkauskas says, “subtle technologies now monitor everyone’s movements.”

Andreas Rutkauskas, Monument #162B, Alaska / Yukon, 2011. Inkjet print, 132 x 165 cm. Collection of the artist.

Andreas Rutkauskas, Monument #162B, Alaska / Yukon, 2011. Inkjet print, 132 x 165 cm. Collection of the artist.

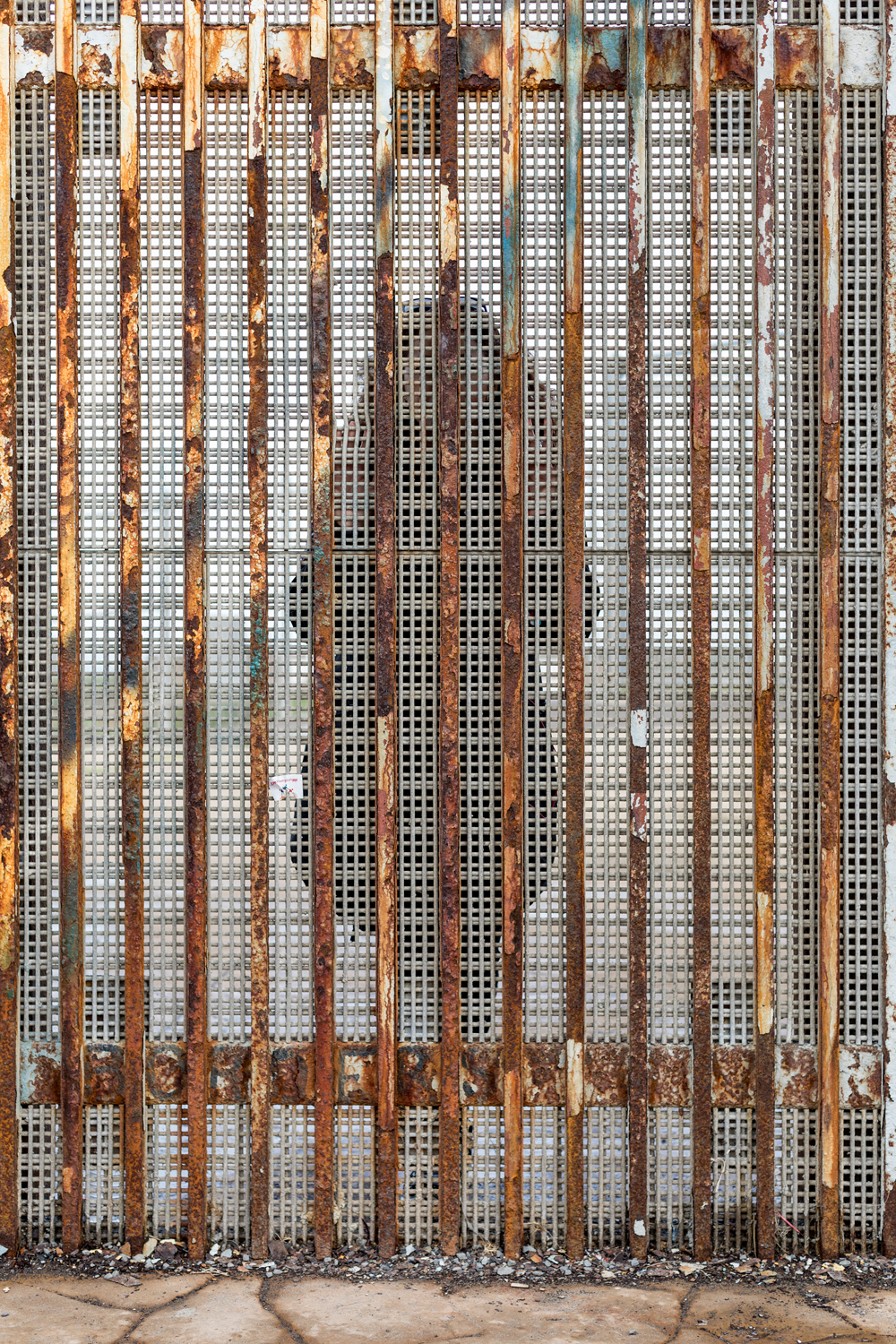

The standout of the CPI exhibitions, found in the spaces after “Gold and Silver,” is the group exhibition “Frontera: Views of the US-Mexico Border,” featuring of Canadian, American and Mexican artists.

In “Frontera,” photographs and videos from 1997 to 2017 offer various angles, literally and metaphorically, through which this much-discussed border can be considered.

Mark Ruwedel, who is based in the US but has a long history in Canada, offers images from Crossing 2001–10 that show tight shots of human traces left behind along the borderline—refuse, documents and even items of clothing lie abandoned under trees and bushes.

Mexican artist Alejandro Cartagena’s stunning portrait Daughter on the USA–Mexico Border Wall, Border Field State Park, California (2017) is blown up and applied directly to the wall in the exhibition, showing the outline of a body behind the border wall’s dividing gates.

Alejandro Cartagena, Daughter on the USA-Mexico Border Wall, Border Field State Park, California, 2017. Digital print. Collection of the artist. Photo: Alejandro Cartagena.

Alejandro Cartagena, Daughter on the USA-Mexico Border Wall, Border Field State Park, California, 2017. Digital print. Collection of the artist. Photo: Alejandro Cartagena.

Humanity’s endeavour to control the vastness of land is arguably most prevalent in Daniel Schwarz’s two accordion books of satellite images from Google Maps depicting the US-Mexico border from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. States Border: The Mexico-United States Border (2015), all 25.4 metres of it, is displayed stretched out across a long, narrow table dividing the room.

Whereas “Gold and Silver” feels nostalgic and even glamourized, “Frontera” is current and raw. Notably, Swiss-born artist Adrien Missika’s series We did not cross the border, the border crossed us (2014) depicts various species of cacti actively defying humanity’s attempt to rule the land: most of these cacti are so old they predate current US–Mexico borders, curator Lebart tells me: “some [that] were born Mexican now find themselves American, and vice versa.”

Rose Ekins is a curator and arts writer based in Ottawa.

A detail of a bronze plant in Remedy (2017) by Anna Williams. Photo: David Barbour.

A detail of a bronze plant in Remedy (2017) by Anna Williams. Photo: David Barbour.