As a conversation between body, land and water, art by Indigenous women is potent medicine—it combats the colonial agenda and penetrates a monolithic art world. In waterways, there is a constant flow of intergenerational knowledge passing through the lakes, rivers and oceans; every body of water holds a spirit, a history and informs the land. Various landscapes and bodies of water shape our identity, culture and sense of belonging—and in turn, Indigenous art can offer an embodiment, a re-mapping and a reclaiming of our traditional lands, waters and bodies.

Not long after I left my ancestral Mi’kmaq Newfoundland and Labrador territory, I took a bus from Oshawa to Peterborough to be closer to lakes, as I was growing estranged from the land in big-box shopping-strip Ontario. As I walked into Artspace, and its recent exhibition “Olivia Whetung: tibewh,” I felt an ancestral embrace—the same feeling that overcomes my body when standing at shoreline and looking into the horizon beyond water. Indigenous art is a point of entry, and offers an imagined space of arrival.

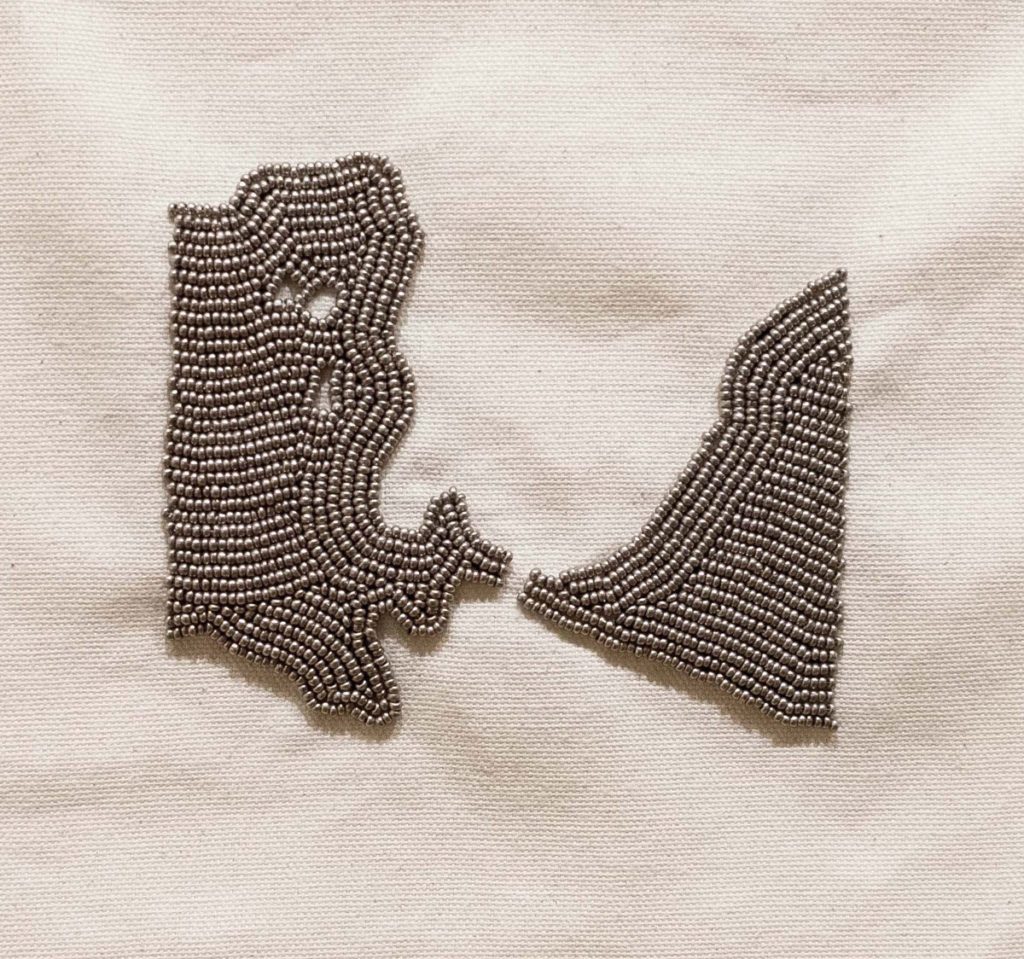

Two of the beaded pieces in “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

Two of the beaded pieces in “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

Anishinaabekwe artist Olivia Whetung’s “tibewh,” which translates from Anishinaabemowin to “a body of water, or shoreline you are in, or on,” taps into an ancestral re-mapping of the Trent-Severn Waterway. Much like the linked-locked waters it depicts, “tibewh” honours a shared shoreline between Indigenous and non-Indigenous vistas—yet it also questions viewers, and asks settlers and non-settlers to consider their relationship to these unceded and unsurrendered territories.

Through beadwork reinterpretations of each of the 42 locks along the 386 kilometres of Trent-Severn Waterway, Whetung’s Anishinaabekwe practice suggests a connection to the land that reaches far beyond confederation’s understanding of Turtle Island. The artist asks viewers, What is land? What is water? Who does it belong to? And also: What are our responsibilities to these lands and waters we occupy? How do we mark and enact that responsibility?

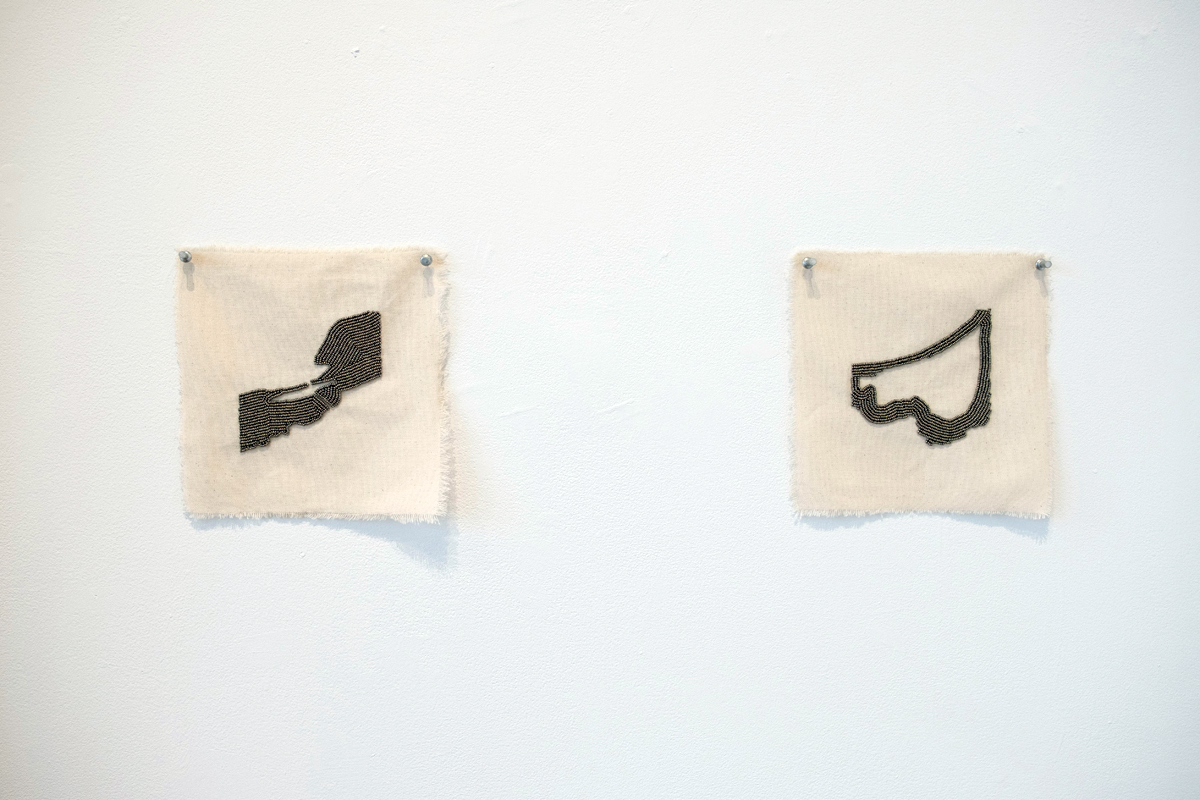

A piece from “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

A piece from “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

As a member of Curve Lake First Nation, roughly 25 kilometres northeast of Peterborough, Whetung makes work that takes root in the lands and waters of her ancestors. “tibewh” is a stunning beadwork re-orientation of the Trent-Severn Waterway, while also being more than that: namely, an exhibition that charts an Indigenous relationship to colonized waters.

Whetung witnesses each of the locks, and the bodies of water they separate, along the Trent-Severn from a bird’s-eye view. These beaded waterways are images not from the lip of the shoreline, but from above—almost as if from the Creator’s vantage point. They remind viewers we are all bodies locked by land, yet made of water.

Just as each square in this exhibition is uniquely beaded, each viewer must assess their own unique relationship to the bodies of water depicted, and consider the physical, ecological and emotional dimensions of that relationship. Whetung invites us to consider the water as body, and land as canvas.

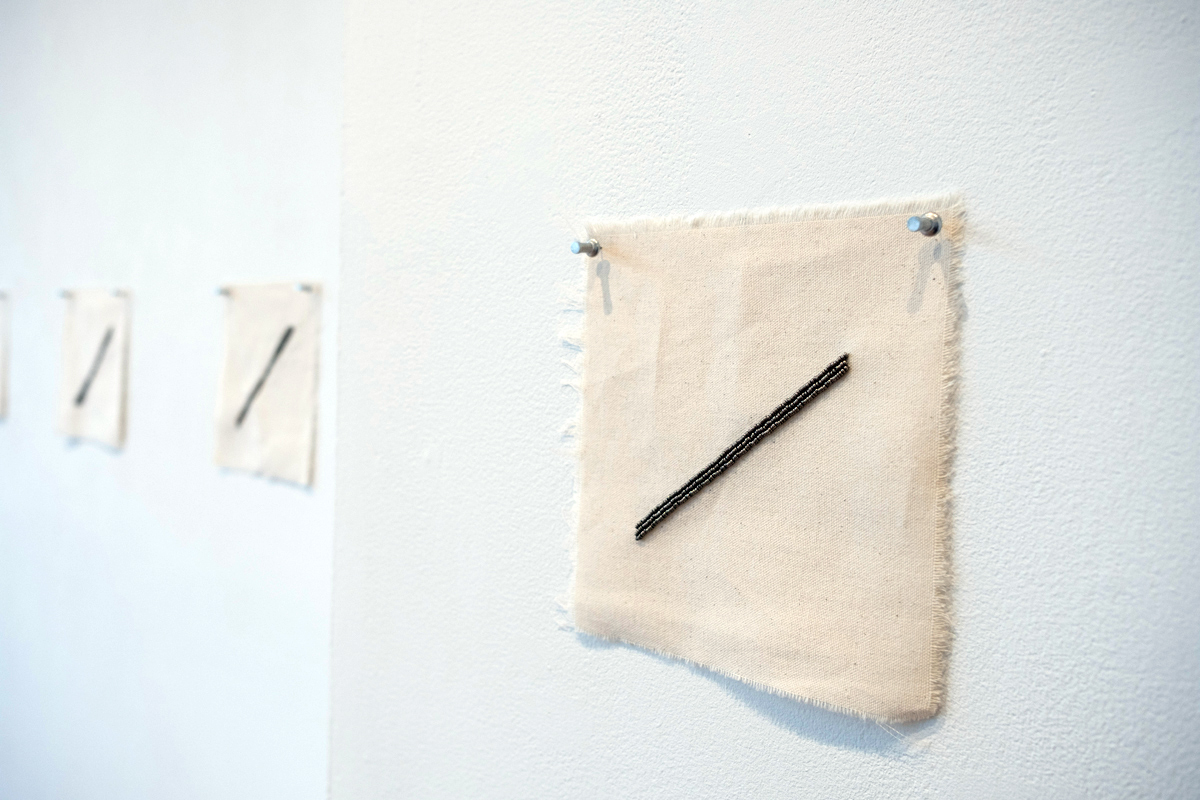

A view of some of the beaded works in “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

A view of some of the beaded works in “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

Given that Ontario tourism imagery tends to embed the narratives of colonial Canada, Whetung’s careful beading over of each body of water also reclaims what has become a cultural signifier of Peterborough and the Kawarthas. The Trent-Severn Waterway connects Niigaani-gichigami/Lake Ontario at Trenton in the southeast to Naadowewi-gichigami/Lake Huron at Port Severn in the northwest, and it meets the Kawartha Lakes, Zaagaata Igiwan/the Trent and Odoonabii-Ziibi/Otonabee Rivers, among others. The Trent-Severn Waterway has status as a National Historic Site, and it is protected through Parks Canada, yet on the 150th anniversary of Confederation—another act of assimilation and Indigenous erasure—Whetung’s work reminds that this system of travel has, for millennia, been filled with Indigenous species, spirits, waters and rivers.

Despite a limited access to the Anishinaabe language growing up, Olivia Whetung started reclaiming her ancestral tongue during her BFA at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, where she minored in Anishinaabemowin—a means to root herself and her practice in the language of her ancestors. As a recent MFA graduate from the University of British Columbia, Whetung makes beadwork that embodies what it means to speak as an artist from Anishinaabe language; her art becomes both decolonial act and decolonial witness.

A wider view of the exhibition “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

A wider view of the exhibition “Olivia Whetung: tibewh” at Artspace Peterborough. Photo: Matt + Steph.

It is worth noting, too, that the Trent-Severn Waterway was originally a military route; issues of colonial mapping and control also come up in the very form of Whetung’s work. “tibewh” features 42 canvas cloths hung horizontally, all perfectly aligned on the walls of Artspace Gallery. Yet the lines of beads on each cloth tend to curve and bend, with straight lines mostly surfacing in spots where the Trent-Severn splits or divides water and land.

As a result, “tibewh” suggests how intersecting passages of water have been colonized in attempt to contain, control and exploit. Though her source imagery for each lock is drawn from Google Maps, Whetung’s reworking of this imagery offers an attempt at re-writing, re-mapping and re-tracing the ancient memory of water.

As part of a decolonial practice, Olivia Whetung works with the land, her ancestors and traditional knowledge systems of the Indigenous people of the Anishinaabe territory. In “tibewh,” she fuses ancestral knowledge and contemporary technology to create an exhibition that is both political and provocative—an artistic retelling of traditional territory and settlement.

Shannon Webb-Campbell (@shannonwc) is a Mi’kmaq poet, writer and critic.