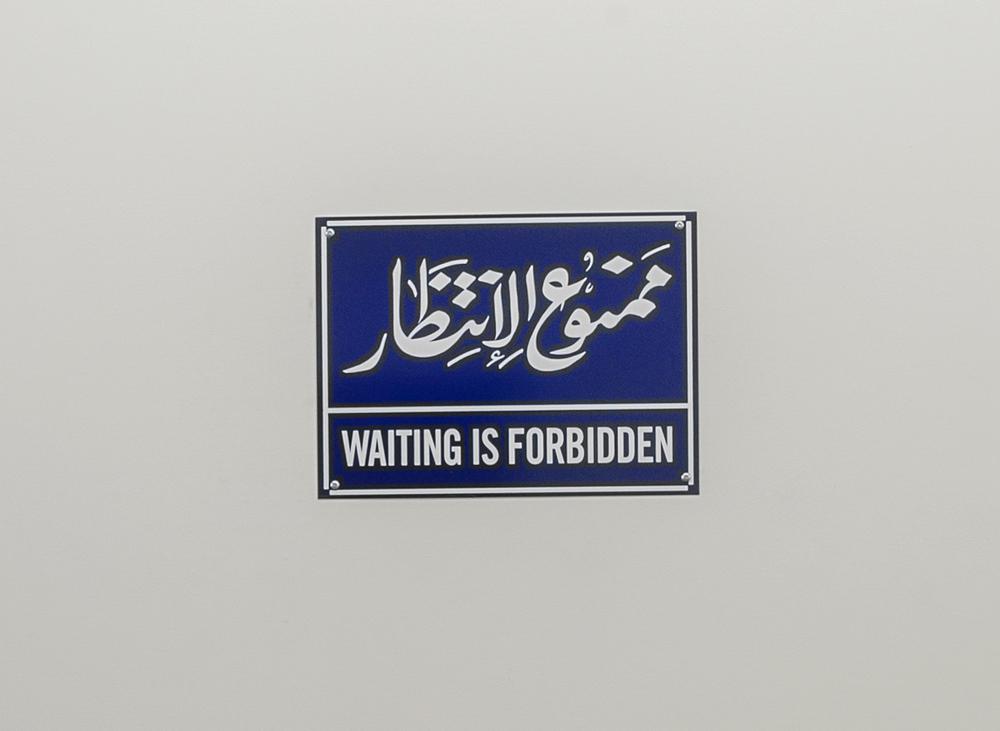

“WAITING IS FORBIDDEN,” indicates the blue enamel plaque that hung at the entrance of Mona Hatoum’s recent exhibition at Galerie René Blouin in Montreal. Positioned high on the gallery wall, the plaque also contains the same warning in Arabic script, apposed with its literal translation in English—though Hatoum contends that the translation should have been “No stopping and no loitering.” Setting the two languages side by side in this artwork suggests the ambiguity that arises when words resist precise translation.

Hatoum’s sign evokes the unsettling experience of someone who has migrated from one culture to another, and demonstrates a sense of instability that may have been nourished by the artist’s personal experience with exile. Born in Beirut in 1952 to a Palestinian family, Hatoum grew up in an environment made unstable by the omnipresent threat of war. She has been living in London since 1975, when a brief visit was extended indefinitely following the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War.

This exhibition brought together a range of leitmotifs that pervade Hatoum’s oeuvre. In the late 1980s, she shifted away from performance and video art to focus on sculpture and installation. Since then, Hatoum has used an elastic and poetic visual language to create works that echo her early performances. The materials she chooses, which include hair, toilet paper and miniature toy soldiers, often have a physical impact upon the viewer. Whether she is using her own hair and bodily fluids as materials, or creating works that appeal directly to the viewer’s own corporeality, the body is always a central consideration in her works.

Over My Dead Body (2005), first created as a billboard in 1988 and displayed in urban areas, is a black-and-white photograph of Hatoum’s face in profile. Strong and defiant in her gaze, she confronts a tiny toy soldier perched on her nose who points his weapon between her eyes. The title of the work, printed in bold capital letters beside her face, implies a prevalent and undeniable reality that is difficult to reduce in stature. Whereas the expression “over my dead body” proclaims the hostility and resistance that Hatoum embodies, in this encounter the power relationship is humorously reversed as the civilian challenges and dominates the armed soldier.

The figure of the toy soldier recurs in Round and Round (2007), a sculpture created from a circle of miniature armed figurines cast in bronze and placed on a square table. The table is the height and size of one that might support a lamp in a living room—but while the home is often associated with familiarity and safety, the everyday objects in Round and Round are arranged to evoke danger and futility. The circular formation gives the impression that the military men are perpetually pursuing each other, arranged in a circuit of mutual threat that connects childhood games with the vicious cycles of war and violence.

The subject of border disputes often arises in Hatoum’s recent sculptures, and her works —particularly those that deal with the process of delineating boundaries—disclose the instability of precarious geographies. In Shift (2012), Hatoum transforms a wool carpet, an object often associated with the comfort of home, into a site of potential risk and alienation. The floor piece depicts a black world map overlaid with yellow concentric rings, the kind sometimes used to track seismic activity, that expose the entire world as a perilous and alarming danger zone. Although the carpet was woven as a single piece, it is divided into multiple vertical sections that are misaligned. The map’s coherence is disrupted and the continents are severed by shifted segments that do not line up. The work outlines a violently disjointed world that resembles a fractured shooting target, signalling the threat of global catastrophes that could destroy Earth at any moment.

If in Shift Hatoum reveals the instability of surfaces we walk on, in Projection (velvet) (2013), she reframes the entire world as unfamiliar and desolate. A world map made from fragile silk velvet hangs on a metal rod. The sizes and shapes of the continents on this map may not be immediately recognizable to many North American viewers, as its configuration is based on a Gall-Peters Projection, which attempts to present land masses according to their relative proportional sizes, rather than the more commonly familiar Mercator Projection, which alters the size and shape of continents and makes Northern-hemisphere territories appear larger than they are. Hatoum’s land masses, which have been etched out of the velvet with a laser, resemble worn-out patches that come together to form an exploited geography of depleted terrains or eroded landscapes. The colour of dark-brown soil, the recessed outlines of the map appear to be submerged into protruding bodies of water. The title of the work suggests a bleak, uncertain forecast for the future, evoking questions and uncertainties rather than grounded answers.

Hatoum often uses her own body to disrupt expectations and challenge corporeal boundaries. It is only upon closer inspection that viewers might discern the bodily dispersals that Hatoum has used to make Stream (centre) (2013)—namely, strands of human hair that have been painstakingly threaded through a piece of toilet paper. A few pieces of hair resist being contained to the orderly, straight stitches; like loose threads, the excess strands unfurl, suggesting the chaos of uncontainable bodily waste. In a series of three works titled Hair Drawing (2003), almost imperceptible pieces of Hatoum’s own hair are dispersed on handmade paper. Hair is often what remains when a body begins to fall apart, and its threadlike link to loss is derived from its durability and capacity to outlive the human body. Drawing without a pencil, Hatoum makes her body the object of displacement as she collects and composes with her own dark curls. She brings together the allure of a material that must be covered by a veil in many cultures with the threat of disintegration, the precariousness of life with the persistence of human tissue. Through her use of hair as material, Hatoum entangles disparate notions about bodily products, and their ability to both attract and repulse.

Hatoum explores the tensions inherent within one form in a work that brings to mind bodily functions and contradictions. In Korb IV (2014), two crimson hand-blown glass shapes are conjoined and confined to a cage-like metal basket on the floor. Evoking two connected hearts, lungs or cells, they seem to have expanded like organic forms, a cancerous growth or a burgeoning love. The inseparable forms were made by two glass-blowers working in unison within the metal container. In this work, Hatoum places the fragile malleability of glass and the rigid strength of steel side by side. Does the basket protect or imprison these forms? Hatoum has created an inconclusive situation that reverberates with the disorientation of displacement.

What happens when we are confronted with ambiguity, when boundaries are disrupted, when order and chaos are forced to co-exist? The possible readings and destabilizations that emerge from Hatoum’s poignant works persuade viewers to re-examine their place in an unfamiliar world, and movement becomes unavoidable because even the ground beneath our feet seems to be constantly shifting. If waiting is forbidden and dislocation is omnipresent, Hatoum compels her viewers to re-evaluate the contradictions now inherent in many human lives.