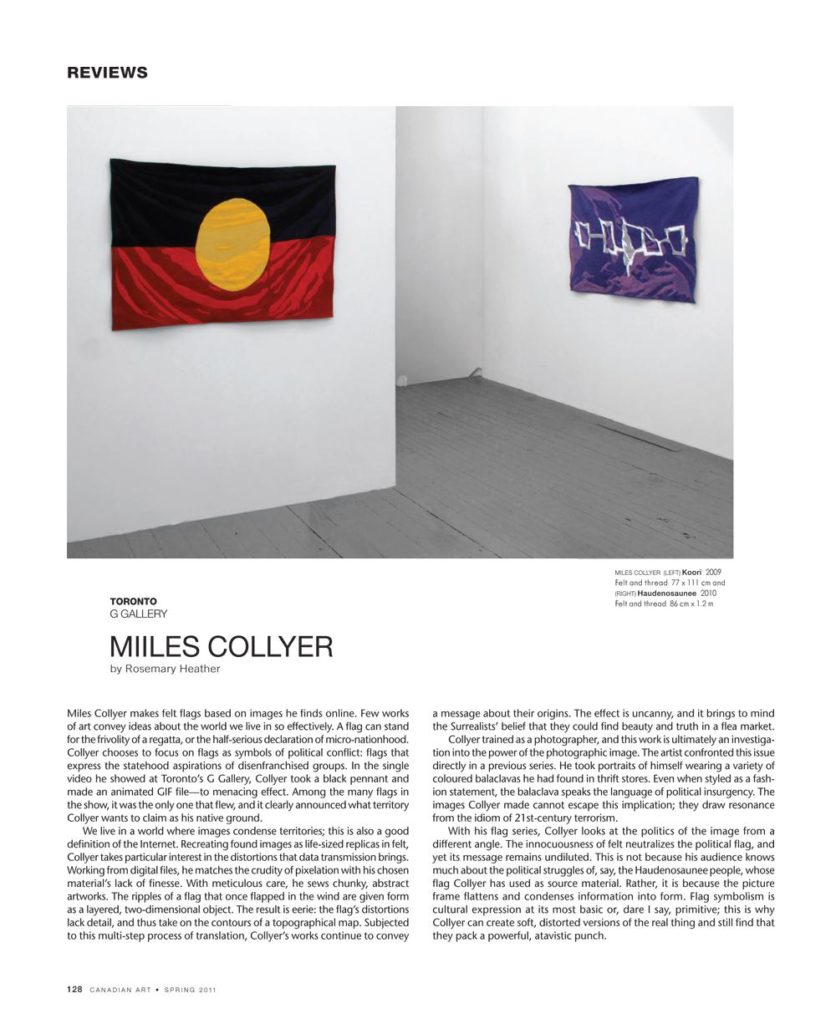

Miles Collyer makes felt flags based on images he finds online. Few works of art convey ideas about the world we live in so effectively. A flag can stand for the frivolity of a regatta, or the half-serious declaration of micro-nationhood. Collyer chooses to focus on flags as symbols of political conflict: flags that express the statehood aspirations of disenfranchised groups. In the single video he showed at Toronto’s G Gallery, Collyer took a black pennant and made an animated GIF file—to menacing effect. Among the many flags in the show, it was the only one that flew, and it clearly announced what territory Collyer wants to claim as his native ground.

We live in a world where images condense territories; this is also a good definition of the Internet. Recreating found images as life-sized replicas in felt, Collyer takes particular interest in the distortions that data transmission brings. Working from digital files, he matches the crudity of pixelation with his chosen material’s lack of finesse. With meticulous care, he sews chunky, abstract artworks. The ripples of a flag that once flapped in the wind are given form as a layered, two-dimensional object. The result is eerie: the flag’s distortions lack detail, and thus take on the contours of a topographical map. Subjected to this multi-step process of translation, Collyer’s works continue to convey a message about their origins. The effect is uncanny, and it brings to mind the Surrealists’ belief that they could find beauty and truth in a flea market.

Collyer trained as a photographer, and this work is ultimately an investigation into the power of the photographic image. The artist confronted this issue directly in a previous series. He took portraits of himself wearing a variety of coloured balaclavas he had found in thrift stores. Even when styled as a fashion statement, the balaclava speaks the language of political insurgency. The images Collyer made cannot escape this implication; they draw resonance from the idiom of 21st-century terrorism.

With his flag series, Collyer looks at the politics of the image from a different angle. The innocuousness of felt neutralizes the political flag, and yet its message remains undiluted. This is not because his audience knows much about the political struggles of, say, the Haudenosaunee people, whose flag Collyer has used as source material. Rather, it is because the picture frame flattens and condenses information into form. Flag symbolism is cultural expression at its most basic or, dare I say, primitive; this is why Collyer can create soft, distorted versions of the real thing and still find that they pack a powerful, atavistic punch.

This is an article from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art