Michael Snow is an unusual case of an artist best known for his least conventionally accessible works. Snow’s legacy will always be defined by in his groundbreaking structuralist films, especially the 1967 masterpiece Wavelength, even as opportunities to experience those works as they were meant to be seen become increasingly rare. (Snow has wryly addressed this phenomenon with the digital re-cut WVLNT (Wavelength For Those Who Don’t Have the Time) in 2003). However, the 84-year-old artist has a wide-ranging practice that includes painting, sculpture, photography, installation, and experimental music.

Snow has been tirelessly active in the art world for more than half a century, and yet much of his work remains little-known and under-appreciated—in part because he’s never slowed down enough for his various bodies of work to be fully assessed. This makes his oeuvre particularly ripe for “rediscovery” via retrospectives in major institutions justifiably eager to celebrate Snow’s diverse achievements for a wider public. In 2012, the Art Gallery of Ontario showcased Snow’s sculptures with its lauded exhibition “Objects of Vision.” Now, the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s “Photo-Centric” shines the spotlight on a selection of his photographic work from 1962 to 2003.

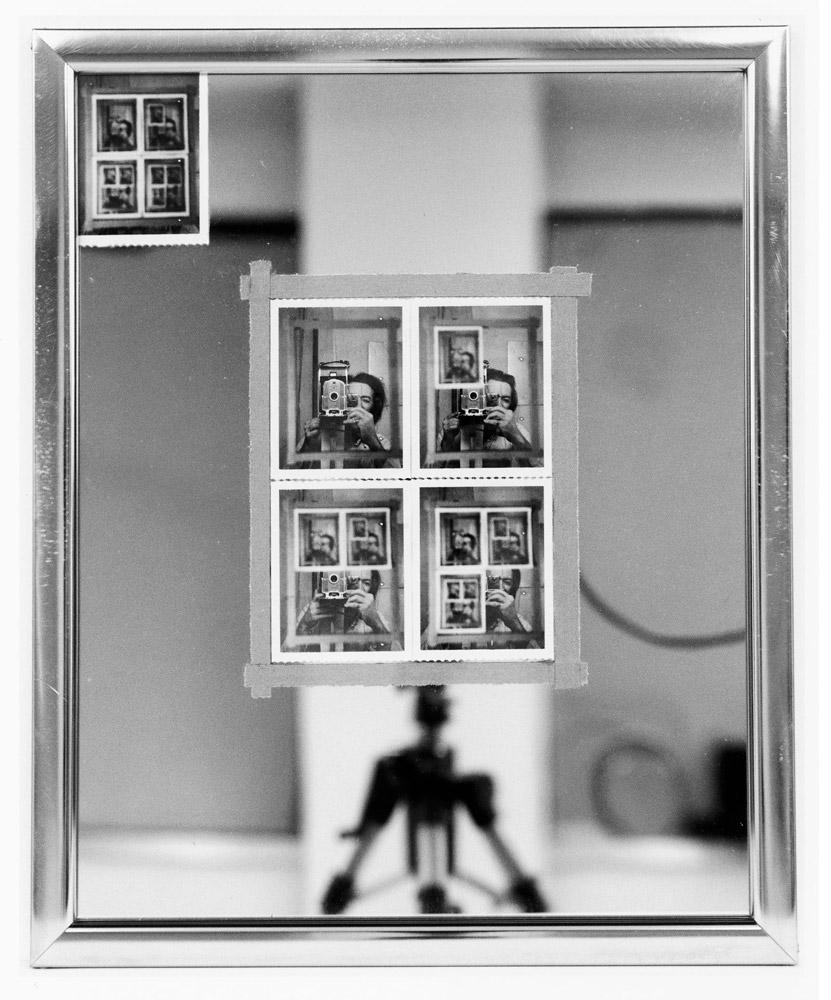

“Objects of Vision” would have been a good title for this Philadelphia show as well, since Snow is primarily interested in the way photography creates objects that serve to replicate, complicate and reformulate optical experiences. As with his films and videos, Snow’s photographic work shows little interest in either documentary or narrative image-making, other than to occasionally acknowledge that these are genres in which photography can engage. Instead, he emphasizes the materiality of the medium to investigate its formal and conceptual foundations. The works in “Photo-Centric” simultaneously construct and dismantle apparatuses of vision, creating cognitive and physical stumbling blocks that trip up the usually unreflective processes of looking in general and looking at photography in particular.

The PMA’s exhibition, which was organized by assistant curator of contemporary art Adelina Vlas in close collaboration with Snow, is housed in a surprisingly small space for such an ambitious retrospective. However, the unfussy and somewhat overstuffed quality of the show complements the works on display. Only a small portion of the exhibition consists of conventional photographs hanging on the wall. Much of the show combines elements of painting, sculpture and installation, and Snow frequently asks viewers to physically engage with the works. In Crouch, Leap, Land (1970), for example, three black and white photos hang from the ceiling so that they face the gallery floor. Viewers have to crouch down and look up to see the photos, which depict a nude woman crouching, leaping and landing as shot through a clear surface from directly under the model.

Digest (1970) invites even more active participation. The work presents an aluminum container filled with dark grey resin alongside a stack of 23 laminated colour photographs. The stack of photographs is roughly the same height as the resin, while the images offer life-scale representations of the container as seen from above at 23 successive stages of it being filled. As we examine the stack of photographs (wearing white gloves and supervised by a gallery attendant), we uncover, layer by layer, the various objects that are encased in the resin. This excavation of a photographic simulacrum, which appears to (but might not) reveal invisible (thus unverifiable) fragments of a past reality, functions as a kind of playful object lesson on how photography functions—or seems to.

This kind of affable, tongue-in-cheek didacticism runs through the whole show. In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, Snow breaks down the works mostly according to formal categories such as “Stasis,” “Simultaneity and Sequence,” “Illumination,” and “Cropping and Framing.” His working method seems to be to catalogue all the qualities that define photography, and in doing so creates photographic works that defy what we usually think of as photographs. The grids that are a recurrent motif in many works indicate the indexical aspect of Snow’s project, as if he is patiently and endlessly impelled to point out, “Photography does this, and this and this…but also this, and this… like this, and this….”

As Show states in a catalogue essay, “to extend the depth of what is called ‘art’ into photography requires not choosing nobler subjects, but rather making available to the spectator the amazing transformation the subject undergoes to become the photograph.” The works in the show explore the various elements of this transformation in ways that range from humourously literal to perplexingly complex.

In the former, more literal, category is Press (1969), which dramatizes the transformation from three to two dimensions. Snow photographed a series of objects that he had flattened by clamping them between sheets of clear plastic (the objects include dead fish, an egg, and a tube of toothpaste). The finished work displays these photographs, along with two self-portraits, clamped between sheets of Plexiglas mounted in a 4-by-4 grid that rests on a large piece of wood—a protruding contraption that mirrors the mechanics of the work’s production.

An even simpler work, Multiplication Table (1977), explores scale by presenting a photograph of a small drawing of a table, along with the pencil that produced it, magnified to the size of an actual table. If the conceptual puns behind works like this and a few others in the show—such as Door (1979) and Midnight Blue (1973–74)—can seem a bit like one-liners, their execution is still usually impressive. The meticulously thought-through presentation often includes unusual elements that add unexpected resonance. Such details include the way the bottom edge of Multiplication Table folds oddly onto the floor, which allows the legs of the sketch to touch the floor as would an actual table, but which also makes the frameless photograph resemble the drafting paper it depicts.

In contrast is a more intricate and challenging work like Powers of Two (2003), a large, double-sided composition presented on four transparency panels suspended from above, somewhat like an imposing curtain. The theatrically staged and garishly lit composition depicts a couple having sex in a bedroom. The image is the same on both sides, but this sameness becomes a difference: otherwise unremarkable details suddenly appear unnatural, like the door that looks to be mounted the wrong way from one side. The cognitive confusion is compounded by the fact that the woman on the bed is staring out at us from both sides of the image. We also start to notice other odd elements that have nothing to do with the two-sidedness, such as an empty picture frame above the bed and a mirror on the wall reflecting/impersonating a window. The double-sided device is a sort of sly red herring, a MacGuffin that impels us to into attentiveness via uncanny misdirection. The work ultimately functions as a wry allegory about the blatant yet elusive artificiality that is the natural state of a photographic image.

Powers of Two is also good example of the way Snow tends to undercut his more conventionally pictorial compositions with a kind of conceptually precise and calculated material shabbiness. The other large-scale quasi-narrative work in the show is In Medias Res (1998), a colourful, bird’s-eye view of a large rug on top of which two men and a woman chase after an escaped bird. As with Powers…, In Medias Res is rendered plastic and installed as much like a piece of furniture as an artwork: here, the photograph is glued to Lexan and laid, rug-like, on the floor. Such strategies nudge the works definitively out of the realm of purely representative images, forcing us to reckon with them as physical objects.

There aren’t necessarily any standalone masterpieces in “Photo-Centric,” though there are many highlights I haven’t even mentioned, including iris-IRIS (1979), Immediate Delivery (1998) and Line Drawing with Synapse (2003). However, while some works might be more rewarding as individual pieces than others, they all benefit from the context of the surrounding work. The cumulative impact of the exhibition as a whole far exceeds the effect of any single piece. As presented by Vlas, Snow’s photographic projects emerge as an incredibly cohesive and rich body of work, thematically focused yet formally inventive and adventurous.

Some of the ways the show is contextualized by the PMA—in the catalogue and press materials, and at the public discussion I attended between Snow and Vlas—can be a bit grating. In general, the “playful” trompe l’oeil aspects of the work tend to be somewhat overemphasized. The illusions and the puns are certainly there, but they are intended as a way into the work, not out of it; they serve to strategically perplex not as punchlines.

There is also a somewhat misguided, if half-hearted, attempt to cast Snow as a grandmaster of the pictorial arts alongside the likes of Manet, Cezanne and Velazquez. Some of this is undoubtedly little more than an excuse for predictable boasting about the PMA’s large collection. However, it still comes off as forced, and it actually undermines the exhibition’s strengths, which demonstrate that Snow’s mastery is simply of a different order.

For all the art-world acclaim Snow has garnered over his long career, he continues to be something of a termite artist according to critic and painter Manny Farber’s distinction in “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art.” Although Farber wrote that essay in 1962, a few years before he became one the early, enthusiastic American supporters of Snow’s films, his description of termite art gels well with Snow’s approach: “it feels its way through walls of particularization, with no sign that the artist has any object in mind other than eating away the immediate boundaries of his art, and turning these boundaries into conditions of the next achievement.”

Grandiosity and hyperbole—which characterize the over-wrought, masterpiece-aspiring notion of “white elephant” art for Farber—are anathema to Snow’s sensibility. Even amidst the institutional hype of a major late-career retrospective, “Photo-Centric” manages to portray Snow as the rigorous, industrious, stubbornly modest and restlessly ambitious artist he has always insisted on remaining.